Editor’s note: This story from 1966 contains dated language that is no longer used today. In the interest of keeping a historical record, it appears here as it was originally published.

By historical accident he happened to play at a time when the rules and strategies of both hockey and football served to spotlight and dramatize his peculiar abilities. It was the age of seven-man hockey, no forward passing and no substitutions; he played the position of “rover,” the offensive superstar permitted to roam all over the ice. The typical play was for him to take a rebound at his own end, circle the goal to pick up speed, and then tear down the length of the ice, by the rules unable to forward pass; because of the no-substitution rule and his phenomenal endurance, this went on all night. Because of the further accident that Princeton at that time had no rink of its own, he always played in cities before big crowds; whenever he got the puck and took off, the crowd would jump to its feet and shout, “Here he comes!” The sportswriter Lawrence Perry described the scene when the sign Hobey Baker Plays Tonight would go up:

On nights Baker would be scheduled to play, the scene outside and inside the St. Nicholas Rink would resemble a night at the opera. A line of limousines would stretch from Columbus Avenue to Central Park West on 66th St. A most fashionable audience would be inside, drawn solely by Baker’s appearance. Men and women went hysterical when Baker flashed down the ice on one of his brilliant runs with the puck. I have never heard such spontaneous cheering for an athlete as greeted him a hundred times a night and never expect to again.

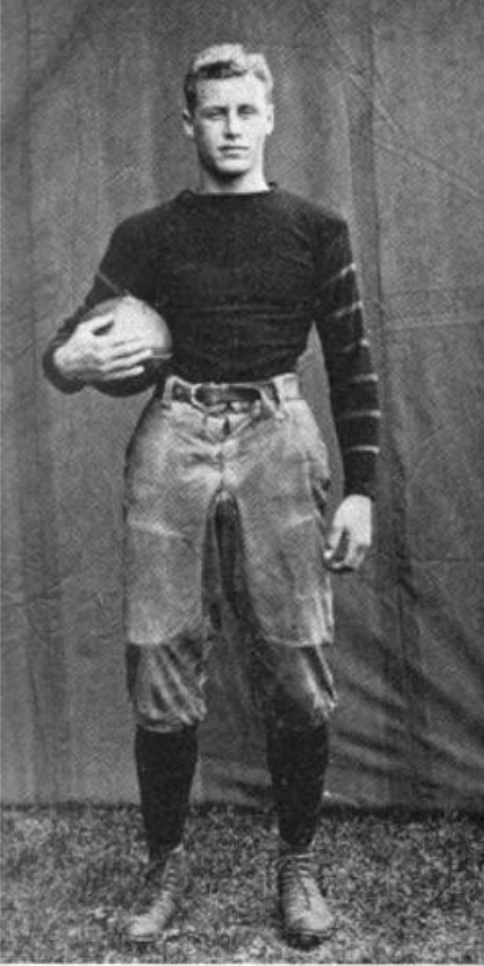

The whole atmosphere was electric when he was playing. Everybody would just stand up when he got the puck or caught a punt. Never wore a headguard in football and I remember that great shock of blond hair – Hobey standing waiting all alone. He was the only player on the field you looked at, the only player you saw. He could dropkick from any part of the filed and from any angle. Everything he did was dramatic – because he was a vivid character – had panache, as the French say. He did everything with a kind of showmanship that wasn’t showmanship because it was natural to him. He was a kind of panther. His coordination and footwork were so wonderful that he could take chances and do things that others wouldn’t dare to. He had the faculty of the real athlete – playing his best when he had to. He would drop kick, tackle and run with a kind of feline intelligence, grace and charm – he would make everything look so easy. Never was anybody like Baker.

To a generation brought up on Frank Merriwell, this was heady wine: a combination of Tom Brown and Sir Galahad, a clear case of life imitating art – the superb athlete, mannered, modest, handsome, who was actually a gentleman and an amateur and a sportsman. His Princeton contemporary F. Scott Fitzgerald remembered him as “an ideal worthy of everything in my enthusiastic admiration, yet consummated and expressed in a human being who stood within ten feet of me.” When he was killed in France in 1918, the “old-fashioned” virtues he personified took on a legendary, eternal quality; as one of his friends wrote me, “Hobey was fabulous in the real meaning of the word. He had some quality that destined him to be a fable and it was not entirely his extraordinary athletic ability. Before he had even graduated from college he had become a fable at St. Paul’s and he had only been out of college a year or so before he was a fable at Princeton.”

***

Hobey Baker was a flawless example of that extremely rare human breed – the natural athlete – and to a superlative degree possessed what might be called the four requisites of that unusual species: physique, coordination, toughness, and determination. So striking was his divergence from the normal college boy that he could be called in the biological or genetic sense a “sport.”

Although only five foot nine and 160 pounds, he was heavily muscled, almost muscle-bound. His chest was deep, “like a rock,” his stomach ridged; he had the sloping shoulders of the athlete rather than the square ones of the blacksmith. He was slightly bowlegged, with enormous development of the knees, almost deformed; his ankles were like steel, his feet, curious to relate, flat. Although he could chin himself with one hand (the right), he was saved from the curse of the strong man – the bull neck – by the fact that his was oddly narrow, of which he was acutely self-conscious; he was determined to thicken that neck by special exercises, lying on the floor and arching his back, rocking from side to side.

While he could play any sport, his specialty was “ball” games, in which the basic ability is to coordinate the hand and the eye. Perhaps the most striking instance of his fantastic coordination occurred one college summer visiting a classmate at Manchester, Massachusetts. Three of the boys were tearing around in a Simplex racing car with Hobey in the perilous perch of the jump seat on the right running board, when on a bad curve on a narrow dirt road another car appeared dead ahead; to avoid a head-on collision the Simplex driver threw the wheel over to the left and hit the brakes, catapulting Hobey out like a high diver. Yet in midair he saw he was going to hit a fence and rolled his body like an acrobat so as to strike a wooden gate with his shoulder, dropped lightly to the ground, and trotted back to the car without a bruise! “To me this was one of the most amazing athletic feats I’ve seen in my life,” a companion recalled. “I know darn well he must have known what he was doing, why he wasn’t killed I don’t know. I think he was absolutely fearless.”

Another example of this remarkable ability was a curious stunt which gave him considerable pleasure. As a houseguest he would appear walking down the stairs on his hands, march around the room as if he were standing on his feet, then disappear as he came. He could move any muscle in his back on command, whistle a tune and move the muscle sin perfect rhythm, juggle five balls in the air. With this coordination and physique he could excel in any sport with practice and pick up the rudiments of one in a few minutes. The freshman swimming coach drafted him for the relay team when he saw Hobey casually exercising in the university pool. He ran the hundred-yard dash in ten seconds flat. One day he dropped in on the rifle range in the bottom of the gym; shown how to adjust and use his strap and the proper positions, by the end of the afternoon he fired off a score which was enough to qualify him a place on the university team – this without previous experience. Although he knew nothing of riding, at Meadowbrook they put him on a polo pony and soon he was enthusiastically batting the ball up and down the field, an acceptable player even at that. On a transatlantic crossing he won the ships’ prize at shuffleboard. A junior remembers a glee club stopover at Greenbrier in the spring of 1914: “He is known in memory as a great athlete but he was also a graceful, dignified man personally. He danced well, he was an astonishing person to his companions on the glee club trips because he started out in the morning playing par golf, stopped to do some high dive somersaulting in the swimming pool and after lunch played an exhibition game of tennis with the pro.”

All sports were easy for him, and he was also a fine baseball player, by repute the best outfielder in college, but was kept out of varsity competition by the faculty rule limiting athletes to two sports. However, he chose “contact” sports to major in; not only are they violent, but, since he usually had the ball or the puck, he was the target. Many athletes have been absolute failures in football because they “go down easy” – they don’t like to hit and be hit. What football coaches say they are looking for is a “rock,” a boy who “wouldn’t mind running into a stone wall,” who could, to use another expression of the coaching fraternity, “dive into an empty swimming pool and walk out.” Hobey was a “rock.” For the whole game he could take bone-crushing tackles or fearsome body checks without complaint or even notice, the first back on his feet, never looking back to see who had “got” him. Agile as a cat, he knew how to fall, with no legs or arms sticking out; he had the uncanny knack of always falling forward, regardless of the angle of the tackle. His ability to dodge in every direction, combined with instant reflexes, prevented anyone from getting what the pros call a “cheap shot” – head-on tackle – at him; a highly developed peripheral vision plus a sort of sixth sense told him where the enemy was. His control was so great, his confidence so complete that he wore the absolute minimum of padding (and no helmet), in hockey only the thinnest of gloves – every foot of speed, every featherweight of touch counted; yet he was almost never hurt. His threshold of pain was apparently very high; black and blue all over after a hard hockey game, he would limp over to the opponents’ dressing room and shake hands with every man, saying how much he had enjoyed “a good game.”

***

St. Nick’s hockey was rather different, of course, from the college brand. The club was composed of true amateurs who actually paid to play the game, to recapture some of the violence and excitement of their college days. They were fledgling Wall Street brokers and bankers, mostly from Harvard-Yale-Princeton. “They had money.” One observer remembers, “and [in later life] made more of it.” Five had their own valets, who after a Saturday night game would bring over their tails and white gloves – Hobey used Pyne’s valet – and off the whole team would go to a dance. Another memorable recollection was the way Percy Pyne would step up to the St. Nick’s bar and pull out his own bottle of rock and rye from a specially designed pocket in his fur-collared overcoat.

But if St. Nick’s was pure in spirit, the rest of the league was not. Professional hockey had not yet crossed the border, and for American fans the postgraduate league served as a substitute. Many of the players were “ringers” secretly paid to play, and the Canadians, of course, made no pretense that they were anything except “semi-pros.” There were many Canadians playing on American clubs, and the Canadian style of play was all to prevalent – roughness, body-checking, winning at any cost – hockey at its most characteristic.

The tone of Hobey’s season was set at the start, with a game against the Irish-American Athletic Association. One of its players, an Irishman working at the Fulton Fish Market, recalled: “We were Canadians being paid to play and needed the money – and didn’t intend to be shown up by what we thought was an overrated stuck-up society kid. We decided to give Baker the business and believe me, we knew how. He was slugged, roughed-up, kneed, elbowed, and given every dirty trick in the book. Once our star, a big Indian center named Cree, banged Hobey’s head against the cage and knocked him out for a few seconds. Unfortunately for our plans he skated rings around us and won, 6-3. But after the game he hobbled into our dressing room, shook hands with each of us, and said how much he had enjoyed the game. Cree said he was sorry he had hit Baker’s head but was told to forget it, that’s just part of the game. Thereafter we decided never to do anything like that to Baker again. He was the cleanest and the best hockey player, as well as the finest gentleman I ever met.”

***

Finally his orders came through that he was to leave on December 21 on the night train for Paris. The morning of his departure he had a crisis of conscience, decided it would be unethical for him to desert the squadron which he had so carefully fashioned, and drove over to the commanding general’s office to have his orders countermanded. The general curtly turned down this quixotic plea, and Hobey’s conscience was clear. He arrived back at the field in high spirits, driving the motorcycle himself while the enlisted chauffeur sprawled in the sidecar with his feet on the cowl smoking a big cigar. (“Captain Baker was always doing something like that,” a private commented.) In the officers’ quarters he found his pilots sitting around roasting chestnuts and drinking a mixture of Benedictine and Cognac; exultant, he ran around the room swishing his orders under their envious faces.

Then he suddenly announced he was going to take “one last flight in the old Spad.” A violent argument erupted, because this violated the oldest tradition of the Air Service – never take a “last” flight lest it turn out to be just that. But Hobey was the commanding officer and with his iron confidence ridiculed danger and superstition. Finally he compromised by promising his armaments officer (appropriately enough, his old Princeton preceptor and coach, “Heff Herring), that he would fly straight to Pont à Mousson and back, without acrobatics, a few minutes’ run.

It was a dismal, gray day at Toul Airdrome, with beating rain closing every hangar door and filling every furrow of the farm countryside. As the group of officers, still arguing, approached the squadron hangar, a malign fate intervened; a mechanic stepped out, saluted, and said, “Captain Baker, sir, Number 7 is ready for flight test.” A few days before the Claudel carburetor – a notoriously unreliable piece of equipment – on Number 7 had stuck, resulting in a near accident. Now that the war was over, the green pilot had simply refused to fly it until that temperamental device had been replaced with a Zenith. It was a sticky situation: the prospect was an unpleasant interview, perhaps disciplinary measures for a “new boy”; and the responsibility for the safety of the pilots was still the commanding officer’s. He said, “All right, I’ll take Number 7.” This ritualistic gesture, a symbolic farewell compounded of hubris and nostalgia for the aerial world he had loved so very well, would be performed in a borrowed machine. Now the argument excitedly broke out louder – repaired planes were feared as tricky and dangerous – and even the enlisted men joined in. One sergeant in deliberate insubordination wheeled out Hobey’s own Number 2 from the hangar, but to no avail.

He took off in the rain, and following his invariable pattern held her twenty feet off the ground, gunning the Hispano engine to 2200 rpm, then did a right chandelle (steep climbing turn), leveling off at six hundred feet. After a quarter of a mile the engine quit. He was faced with a split-second decision. In case of engine failure, he had drummed into the minds of his pilots, stick the nose down to regain flying speed and set the plane down straight ahead (without any turns) as best you can. For all its trickiness and unpredictable quirts, the little Spad had one happy virtue, in that I could be crash-landed anywhere – with usually no more harm to the pilot than a bloody nose. Some pilots in France had cracked up as many as a dozen of them, walking away from each crash. After the Armistice Hobey himself had made a forced landing behind the German lines in rugged terrain. But it would be embarrassing, one would imagine, for the commanding officer, the best pilot in the squadron, to “wash out” a ship – and on a completely unnecessary “last” flight.

That any such thoughts even crossed his mind would have been out of character. Hobey didn’t play by the book or fly by the book; with his daring and utter self-confidence he did what was instinctive with him, tried to repeat a stunt he had pulled off on that other day in June. He would get back to the field, land the plane safely and save it. He made a right turn, and without flying speed started to fall off on the down wing. Then he did the only thing that could have saved him: pushed the stick straight down to regain flying speed. If he had had one hundred more feet of altitude he might have been able to get the nose back up. But he didn’t have one hundred more feet, and the plane hit with a sickening crash.

This was originally published in the September 27, 1966 issue of PAW.