Architect Peter Wheelwright ’75 builds stories — in buildings and on paper. A professor emeritus at the Parsons School of Design in New York City, Wheelwright has traded his drafting table for a silver MacBook Pro and has written two novels.

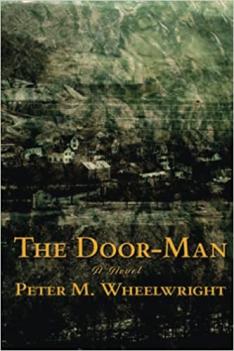

His latest, The Door-Man, comes a decade after the publication of his debut novel, As It Is on Earth, which received a 2013 PEN/Hemingway Honorable Mention for Literary Excellence. The New York Journal of Books calls his new work “a searing chronicle.”

The idea for The Door-Man came when Wheelwright, who has a home in upstate Gallatin, New York, saw an item in a local paper about the doomed Catskills hamlet of Gilboa. Slated to be submerged by a reservoir in 1917, it won a brief reprieve when Winifred Goldring, later the nation’s first female state paleontologist, discovered evidence there of a 350-million-year-old forest.

“I was taken by it. I immediately Googled Goldring, and there she was, sitting on her motorcycle. It just really captured my imagination,” recalls Wheelwright, who made her the novel’s central figure.

In the book, her discovery touches off a multigenerational saga with other real-life characters including New York City Mayor George McClellan 1886 *1889 and his roommate Gaston Drake 1894, the founder of Princeton, Florida, a mill town whose buildings he painted orange and black. Wheelwright takes readers there for a fictionalized retelling of a 1938 child kidnapping and manhunt that was a media spectacle second only to the Lindbergh abduction.

“You can’t make this stuff up,” says Wheelwright, who comes from a family of naturalist writers. He was named after his uncle Peter Matthiessen, the three-time National Book Award winner. His brother Jeff Wheelwright is a science writer.

The book’s title character, Piedmont Livingston Kinsolver, springs from Wheelwright’s lightning-fast imagination. (“I can’t calculate the speed,” he says.) A middle-aged Manhattan doorman born in Princeton, Florida, Kinsolver watches 1990s Central Park as though it were a wild landscape.

Wheelwright prefers to call himself a storyteller, not a writer, and says he is motivated by a tale’s inspirational aspects. “Writing fiction can provoke one’s imagination and knock us off our settled game about what we think we should be,” he says. “It helps us to imagine what we could be in a better world.”

He chaired the Department of Architecture, Interior Design, and Lighting (now renamed as the School of Constructed Environments) at Parsons until 2007, and retired in 2017. He taught design-studio courses that mixed theory, history, and philosophy with an environmental slant.

“When I was head of the school, I was very involved in developing the curriculum around sustainable issues and resilience. So when I discovered this story about Winifred, the fossils, and their relationship to New York City’s water supply system, that was a big connecting key for me,” he says.

His first novel came to life “quickly and easily,” but The Door-Man’s many characters and time span temporarily stymied him. “Writing is like having a herd of 500 head of cattle spread out over the Great Plains,” says Wheelwright. “For me, the cattle are all the aspects of the book — the characters, places, events, things that have happened, and they all have to be corralled.”

But inspiration came shortly after COVID’s onset when he designed and built a 300-square-foot modernist writer’s studio on his home property in Gallatin. Working at a stand-up desk with a Danish wood-burning stove crackling behind him, Wheelwright finished the last half of the book in less than a year. “I was able to get away, and that made all the difference,” he says.

“The training that an architect undergoes really couldn’t prepare one for writing stories much better,” he says. “One of the things a writer has to do is figure out how to structure a story. You need to figure out how to enter it. You need to know how to move through it.”