On Dec. 9, 1967, when William Warren Bradley made his debut as a professional basketball player for the New York Knickerbockers, the event was given press coverage that would have done justice to the Second Coming.

Nineteen nights, nine Knick losses and a new coach later, when the same William Warren was clipped by a young lady driving a sports car and sidelined for three weeks with an ankle injury, one New York paper mentioned the accident in a three-paragraph box buried on the sports pages two days afterward.

The disparity reflected on the plummeting of Bradley’s athletic fortunes as he began National Basketball Association play. Prior to those December days, the sun and the stars seemed made to shine for the Crystal City, Missouri, boy who put Princeton and the Ivy League on the basketball map.

The 6-5, 205-pound forward performed feats that rang like fantasy straight from the imagination of a daydreaming seventh grader. In 83 varsity games, he averaged over 30 points and 12 rebounds; led unheralded Princeton to three Ivy titles and, in his senior year, an astounding third place in the national championships; captured the United States’ gold-medal winning basketball team at the 1964 Olympics in Tokyo; and broke the heart of the Knicks’ front office by passing up pro ball after Princeton in favor of a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford.

The Knicks, a hapless team whose dismal finish the previous season had earned it first pick in the college draft of 1965, nonetheless passed up a Rick Barry in the hand for a Bill Bradley still on the books, picking Princeton’s All-American on the slim hope he would eventually have a change of heart.

“I thought the last time I played for Princeton was going to be my last game,” Bradley recalled recently.

The widely read New Yorker profile on Bradley (Jan. 23, 1965) by John McPhee ’53— later included in McPhee’s biography of Bradley, A Sense of Where You Are—concurred: The article concluded solemnly that Bradley would “have the unique distinction of taking only the name of his college”—no professional name—“with him into the chronicles of the sport.”

But in April, 1967, nearing the completion of his second and final year in England, Oxford’s most renowned athlete decided against the unique distinction.

“It isn’t possible for me to give one simple answer and say, this is the reason for my decision,” Bradley said at a press conference announcing his four-year contract with the Knicks for a reported $500,000. “The main factor, though, was this: I found what I had sort of expected all along, that I really love the game of basketball, and that I want to test myself against the best. It sounds trite, perhaps, but it’s the truth.”

Bradley finished his Oxford studies (philosophy, politics and economics) that June, spent five and a half months on active duty with the Air Force in Texas and reported to his new club, already a third of the way into its 82-game season.

And then the sky fell in.

In his December 9 debut against the Detroit Piston in the old Madison Square Garden, Bradley scored eight points in the mediocre 20 minutes he played. The Knicks dropped the game, 124- 121, and several Bradley miscues—as well as the novice’s two-for-six showing at the free-throw line—loomed large in the final statistics.

A capacity crowd of 18,499 had filled for Garden for Bradley’s first appearance, however: a turn-out over double the Knicks’ customary attendance figures. One sports writer estimated the club’s half-million dollar investment in Bradley was recouped by the end of the season.

The club was winning regularly by the end of the season. Cazzie Russell, overshadowed by Bradley in two memorable games between top-ranked Michigan and Princeton during the 1964- 65 college season, was emerging as the Knicks’ closest thing to Oscar Robertson.

And Bradley ambled along, playing a period or two a game, averaging eight points and a little more than two rebounds and three assists. A decent bench man.

“I always said right from the start I didn’t think Bill would be a superstar as a pro,” said the man who as coach shared the glory of the Bradley days at Princeton, Willem “Butch” van Breda Kolff. He was sitting in the stands at the new Madison Square Garden one Tuesday night early in the present NBA season prior to a game between the Los Angeles Lakers, who hired him away from Princeton, and the Knicks.

“He didn’t have the physical size and he wasn’t selfish enough or something of that order.” He added, in the same breath, “But I still feel he can become a good 15-point-a-game pro. I know he can play. He hasn’t shown it yet. He’s the type of player you gotta play with. Not of the accepted NBA mold, the one-on-one all-star.” Van Breda Kolff’s face oozed disdain for the accepted NBA mold.

“No, I don’t think he’s very happy. He’s a perfectionist. Perfectionists are never easy to please. He’s trying too hard.”

A few days later, the quiet, 25-year-old athlete agreed with his coach’s analysis. “I know I’m never going to be as good as a lot of players. Simply from the physical abilities alone.

“Basketball is a team sport. Basketball is movement. In many ways it’s the van Breda Kolff game. That’s how it was at Princeton. We played the same way in high school, a style of ball where you helped everyone else, a lot of fast breaking and moving it around…Boston, that’s how they play, and Los Angeles. And sometimes San Francisco. Sometimes they play together…But all the great superstars are one-on-one players.”

There were more than 15,00 persons in the Garden the Tuesday night the Knicks played the Lakers. Van Breda Kolff’s team had won 10 of the last 11 and sat comfortably atop the NBA’s western division with a record of 14-5.

The Knicks had come up with their best game of the year the Saturday night before, topping Boston, 111-100, for a second straight win that brought their record to 8-13. Bradley had played decently but scored only six points. Holzman had moved him back to a forward position after an extended stint in the backcourt.

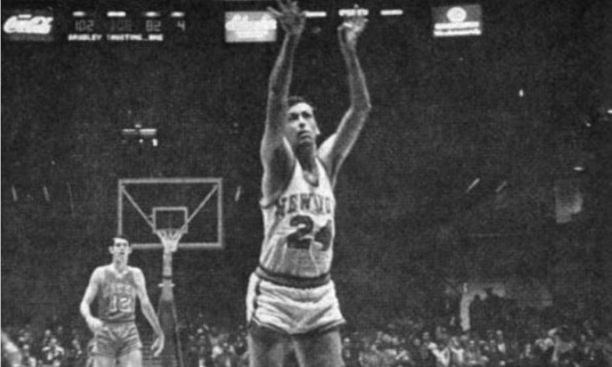

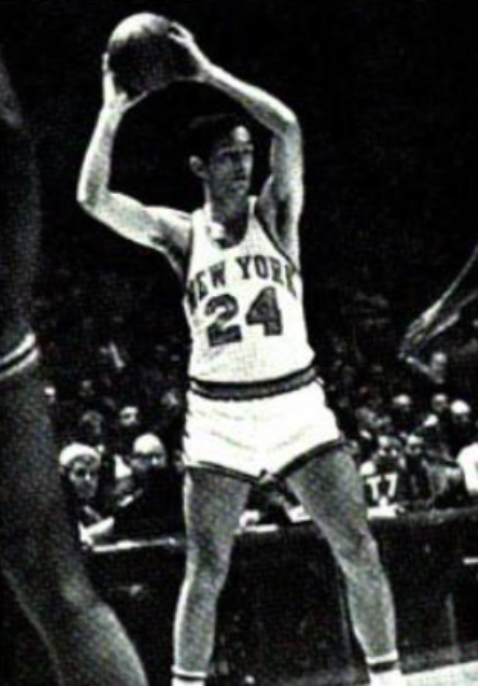

When the buzzer sounded for the teams to end their warm-ups, Bradley, number 24, was the last man off the court, taking one shot and then another and a third, much as a youth paged through a textbook in the seconds before an exam.

He sat near the end of the bench, a towel stretched across his legs and tucked tautly under his knees throughout a drab first quarter while the Lakers fumbled to a 21-12 lead.

When Bradley reported in at the start of the second 12-minute period, a little roar swelled from the stands. A minute later he got the ball in the left corner, leapt and pushed the ball off his right hand into a high, teasing arch that swished through the net on its way down. The crowd cried gleefully.

Bradley’s luck ran cold after the initial bucket. He threw up five more shots before the end of the half and missed all, including a lay-up on a fast-break. The Lakers led at the intermission by seven, 43-37.

Bradley was back on the bench with the towel across his knees at the start of the third quarter. When he came in with five minutes gone, the Lakers were up by 13 points, 64-51. Half a minute later, he threw in a 20-foot jumper from the left corner. Super-star Elgin Baylor scored two for Los Angeles to lead 66-53 with six minutes left in the third quarter.

Then the Knicks tore off nine straight points in the next two minutes with second-year guard Walt Franzier and Bradley leading the way. Both ballhawked up and down the court. Frazier accounted for five of the nine and Bradley two, a 22-foot jumper from out beyond the key. Score: Lakers up, 66-62.

With a little under two minutes left in the third quarter and the Lakers leading 70-67, Bradley was fed the ball on the left side. He cut fast to the baseline. The Lakers’ Tom Hawkins slid with him. Bradley spun at the line, leapt completely around and lofted a jumper at the basket from an incredible angle. It swished. The crowd screamed. Bradley came downcourt and stole the ball.

The magic seemed dead again at the start of the fourth quarter. In three minutes Bradley threw up three shots that bounced off the rim and a fourth from 20 feet out that missed everything. Holzman took him out with 8:22 left. When he returned three minutes later, the Lakers led by 10. He was guarding Baylor. Holzman called for a collapsing full-court, man-to-man press with the clock showing under four minutes left. Two minutes later the Knicks drew even, 97-all. Bradley had three points, a steal and an assist.

The Knicks went over the 100-mark and into the lead on a Bradley jumper from the line with just over a minute left. Knicks up by two with half a minute remaining. A pass to Bradley 25 feet out on the right side. The jump, the arch, the swish and the Knicks win, 104-100. The garden was bedlam. When the man on the public address system announced the individual statistics, the crowd gave a polite cheer as the two highest Knicks scorers, Frazier with 21 points and Walt Bellamy with 17, were read off. As the loudspeaker blared, “Bradley…15,” the crowd roared with sheer delight. In a little room just off the Knicks’ dressing room, Red Holzman was sipping a beer as he talked with reports. Did he think it was Bradley’s best game? “Bill played very well. He made some key buckets,” offered the laconic, 47-year-old coach.

The reporters were not so restrained. Inside the dressing room they flocked around the cubby nearest the door where Bradley’s clothes hung. Emerging from the showers, he parried their questions in a soft, unassuming voice.

“Bill, you really did a great job on Elgin,” said one reporter. “Oh you can’t say that, you can’t say that,” Bradley retorted with a faint look of chagrin. “I was only playing him, what, three, four minutes?” He had held Baylor to two points on foul shots in the five and a half minutes he was on him.

Down the gall an exasperated Butch van Breda Kolff emerged from his team’s closed dressing room. How about Bradley? He was asked. “Oh, he’s the guy that can’t play,” replied the coach in a voice dripping with sarcasm. “Can’t play. Too slow.” Van Breda Kolff waved his hands with exaggerated disdain. “That’s the guy they said can’t play. All the knowledgeable experts. ‘Can’t play.’” Butch sighed. “It’s amusing. It’s getting to be amusing.”

The next night the Knicks lost to the Celtics in Boston, 111-100, despite a strong team effort. Bradley hit eight field goals, missed only five, and added three foul shots for 19 points. “I was sure Bradley had 30,” was Holzman’s comment after the game. The banker’s son from Crystal City was getting his share of the printer’s ink. “I feel a little better about playing basketball now. I feel a little better about playing basketball tonight,” said Bradley two nights later as he sat in an unused Garden dressing room an hour before game time. “I can’t say if I have found the mark. You just can’t make any kind of judgement after playing only one or two games. I haven’t played well enough yet to say I have played well.”

He spoke in a voice at once pleasant-sounding and authoritative. If you put Bradley in a room with five foreigners, none of whom spoke the others’ language, and told the six to keep talking, you would probably have five listening unintelligibly to the sound of the Rhodes scholar’s voice in a few minutes.

“The pro game is much more exciting than college ball. It has its built-in flaws. The 24- second clock causes a lot of mistakes. A well-coached, well-drilled and talented college team probably makes fewer mistakes than a pro team, but I don’t think it is as good. “When I came back from Oxford I hadn’t see basketball in America and in almost two years. It wasn’t until I had played about 15 games in the pros that I saw my first college game. The slowness really impressed me. I think the NBA is definitely more exciting.”

But there was an unspoken qualification in Bradley’s words. He is a basketball priest, a devout follower of the philosophy that “basketball is a team sport, basketball is movement.” He was asked how he felt about professional basketball in comparison with college ball. “I’ve accepted it to the point of not trying to decide which is the better game,” said Bradley. “My contract is for four years. It ends two years after this season. I don’t think I’ll play any more after it.” He made the statement matter-of-factly. “I don’t know what I’ll do after I finish basketball,” he said in response to a question. “Politics attracts me.” He smiled. “So do movies. I like going to movies. Maybe you should turn it around: movies attract me, politics attracts me.

He was asked about life as a professional basketball player. “It was an unknown quantity at the time I made the decision to play whether I would like the NBA life. All the travelling, the ballplaying itself…So far, it’s been all right. The life gives you advantages the average person doesn’t have. Most of the cities we play in, there are friends I know. I enjoy the visiting, keeping up contact with the friends I have made.

“I enjoy the team and the fellows on the team. I enjoy being a part of a team. That doesn’t mean I’m a collective by nature,” he cautioned seriously. “You’re with these guys two hours a day when you’re not travelling. 18 hours when you are. I enjoy the banter, the fun we have. It is a real opportunity to get to know a few people in the personal sense. In a way it’s like you have 11 roommates.”

Did he regret the delay between the time he left Princeton and entered the pros for the study at Oxford? “It didn’t work like that. I didn’t figure on a two-year delay when I went to Oxford. I thought I had played my last game. “You just have to do the things you think at the time are best.” How did he feel about the Princeton years? “I don’t spend my life looking out the window of my apartment on rainy days thinking about how things were. The four years at Princeton were the best thing that ever happened to me. It opened a new world. The friends, the kind of excitements, the intellectual excitements—I’m very grateful for that. It was a stage of my life and I passed through it, and I’m glad for it.” The Knicks’ opponents that Saturday night were the Detroit Pistons, then fifth in the eastern division just ahead of the Knicks and the team Bill Bradley had made his inauspicious debut against one year before.

The Knicks ran them off the court. It was 32-21, New York, at the quarter, and 40-26 with nine minutes left in the second period when Bradley went in. He was superb, throwing in eight points by halftime. The 12,000 fans in the Garden loved his every move. When Detroit’s 6-7 “Happy” Hairston had the audacity to foul the fans’ favorite as he went up for a jumper, the Garden echoed with an angry roar.

In the second half, New York showed signs of pulling one of its patented pratfalls. Detroit, behind by 21 points at one stage and 14 at the half, had sliced the Knick lead to nine with seven minutes left in the third quarter. Bradley returned and put on a passing display, pegging the basketball through invisible alleys between Piston players and into his teammates’ hands. By the end of the quarter the Knicks had their 14-point lead back and from there coasted to a 120-108 win, their fourth in five games. Bradley, playing little more than half the game, totaled 16 points and five assists. In three games he had scored 50 points to pull an 8.3 average up a full point. “I’d like to play on a championship team. That’s always been my ambition in athletics,” Bradley had said before the game. “I was one that never enjoyed a loss in which I scored 40 points.”

The 1964 Olympic team was the only championship team for which Bradley has played. Simenthal, the Italian team Bradley with while at Oxford, faltered during the European Cup Match Games; Princeton lost out in the 1965 NCAA semifinals; even Crystal City High School fell short of a hardwood championship. “Crystal City’s population is about 4,000,” said Bradley as he left the Garden. “Our high school had an enrollment of something like 405, which put us just into the basketball class that included schools with up to 2,000. That’s where all the competition was. We never won the state championship. “In my freshman year we lost in the opening round; in my sophomore year in the quarterfinals; junior year in the semi-finals and senior year in the finals.”

There is another high school which has figured prominently in the Bradley myth. McPhee, Bradley’s biographer, recounted in his profile on the athlete the incident in the summer of 1964 when Bradley was practicing in the gym of the Lawrenceville School near Princeton. The first six shots he tried missed. “You want to know something?” he told McPhee. “That basket is about an inch and a half low.” McPhee measured a few weeks later. It was one and one-eighth inches too low. “When you play this game long enough you can tell when something is wrong,” said Bradley when reminded of the incident. “Take a musician, say a violinist. If he runs his hand along the strings of his instrument,” he said as he swung his right hand along an imaginary violin, “he can tell if it’s out of tune.” Bradley has been playing basketball since he was nine years old. He will be 28 when he retires in two years, as he now plans to. He has not tired of the game. “Basketball is like narcotics in a way,” he laughed. “If you enjoy something, you don’t mind doing it.” “He has reacted very well to his aversities in basketball,” remarked McPhee recently. “I think it improves him. If he were standing around with flashbulbs popping in his eyes because he was able to score 50 points, that would be one thing. I am more impressed with his reaction to the absence of flashbulbs.”

The game is far from tiring of him. The fans applaud Bradley’s every move as if he were a young king fighting to regain a usurped crown. The cheers have not weakened. That Bradley should share the underdoggish lot of the common man has heightened his public’s admiration. “He is ‘The Great White Hope’—literally,” remarked a spectator viewing the Garden crowd. Black players dominate the game of professional basketball. The white middle class dominates the stands. In the Princeton days sportswriters billed Bradley as “The White O”—an Oscar Robertson from the salt shaker. Bradley who has been kiddingly nicknamed “Superman” by his teammates, scoffed at the “White Hope” theory. And Bradley scoffed at the idea that the eyes in the stands see Bradley as their own fulfillment, the archetypal tall, dark and handsome Ivy Leaguer. “I frankly don’t think the people are thinking about that,” he said. A justifiable position. The young man who is Bill Bradley is, to himself, no more a “White Hope” than a “Superman.” Nor is he a sublimination of the American Dream. Nor the once and future governor of Missouri.

For Bradley is exceedingly real. Exceedingly exceptional, but exceedingly real. Cut him, slice him, deify him, embody him, and you still have the same Bradley. The one who lives alone a subway ride from the Garden. The one with the Olympic gold medal. The one who works in Harlem’s Street Academy program. The one with the Oxford degree. The one the shortest of whose shortcomings may indeed be the nets on the courts of the NBA. Or maybe not. His life does not ride on the shots. The perfectionist? “If you proceed from a premise perfection is possible, then it’s legitimate to say I’m a perfectionist.” A cryptic smile. “Speaking within the reference of basketball.”

Success fell with a thud on Bill Bradley and the rest of the Knicks as the NBA season unfolded. After a calamitous opening in which the Knicks dropped 13 of its first 19 encounters, the team transformed their record to 43-21 by mid-February and jumped from fifth place to second before losing steam. Bradley progressed in measure with the team. Two events hastened his court emergence. One was a December trade that sent Knicks Howie Komives, a guard, and Walt Bellamy, an erratic center, to Detroit in exchange for stellar forward Dave DeBusschere. Bradley gained not only a road roommate in the deal but also the chance for more playing time. And he got a regular starting role when Cazzie Russell fractured an ankle and was lost for the season in January. Princeton’s Pride playing 40 to 45 minutes a game, took the pressure in stride. Although his average hovered around the 11-point mark, Bradley splurges engineered a number of Knick wins. He hit a professional high of 28 in February against the Boston Celtics. – C.C.

This was originally published in the March 18, 1969 issue of PAW.