The first classroom in Princeton College to have electric lighting was rigged up by Cyrus Fogg Brackett, a professor of physics who had what we now call the hacker ethic. These were the days of Thomas Edison, and electricity was still the province of visionaries and amateur enthusiasts. In 1880, Brackett patched together a lighting system for his classroom using Edison’s incandescent lamps, a battery system, a dynamo machine, and — because no tools yet existed for measuring electrical power — a certain amount of guesswork as to measurements. (He later invented the “Brackett dynamometer” to help Edison, a friend of his, measure the power output of generators.)

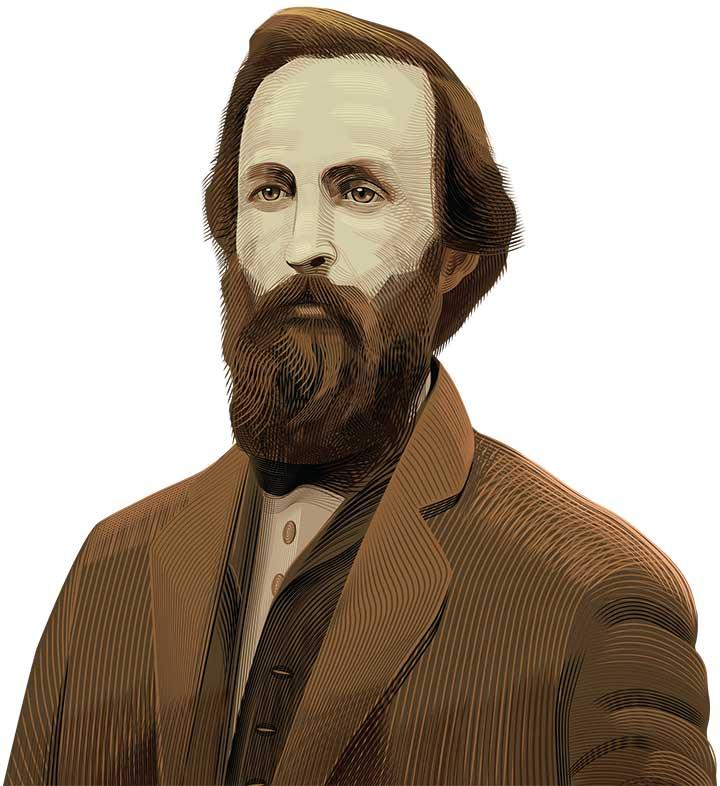

Brackett grew up on a farm in Maine, the son of a carpenter-farmer who probably cultivated his love of ingenious craftsmanship. He worked as a teacher in country schools to support himself through Bowdoin College. After earning an M.D. from the Medical School of Maine, he went to work as a professor of the natural sciences at Bowdoin, then moved to Princeton. His courses in electrical engineering promised to teach the technical bases of the wonders of the age: telephony, telegraphy, electric lighting, electro-chemistry, the new tools being developed for testing and measuring electricity.

He insisted on hands-on practice: His department opened a laboratory where students could build electron tubes, and he himself built the machines he used for practical demonstrations during his lectures.

His students recalled him as irreverent, practical, unconventional but natty in his style of dress: a bicycle suit (in a faculty of dress suits) that he somehow kept meticulously clean despite smoking through two cigars during any given class period. In all things, he insisted on hands-on practice: His department opened a laboratory where students could build electron tubes, and he himself built the machines he used for practical demonstrations during his lectures. He also set up the first telephone line in town; it connected his lab with the office of his friend, chemistry professor LeRoy McCay, in the Prospect Avenue Observatory. The two regularly competed in limerick writing; sadly, their salty limericks were not preserved.

Brackett built such a reputation as an authority on gizmos and gadgets that courts often called on him to give expert testimony in patent-litigation cases, especially those concerning telephone systems. (He went around saying, “The lawyers say there are three classes of witnesses: liars, damned liars, and experts. I am an expert.”) The first director of Princeton’s School of Electrical Engineering, even after retiring in 1908 Brackett continued to hack around in any field that took his fancy, designing optical instruments, electric batteries, and silly musical instruments. A Princeton professor who moved into Brackett’s house following his death told a historian that “when he moved in, there was still in the front room a small organ that had been rigged up by the good doctor so that he could play it with his feet. It was his habit to sit in front of this organ and play his violin while he accompanied himself with the foot-operated organ.”