On March 19, after I and 40 million other Californians were told to shelter in place, I fished out my worn copy of Albert Camus’s The Plague. I was writing a letter to a friend and wanted to remind myself of what I’d internalized from the book when I first read it. As the storm cloud gathered and darkened, and each day’s press conference got grimmer, as the plague of our time released its ravages, I flitted from page to page, scanning fluorescent pink lines made with a highlighter, reading my own scribbled notes, searching for sentences to help me sink into the understandings I have carried with me for more than 45 years. Then I realized that flitting from page to page would not do. I needed to reread the entire thing.

I was assigned The Plague as a junior at Punahou School in Honolulu, when taking a bracing class called Ideas in Western Literature. We had started the semester with Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha but moved quickly onto European existentialism, starting with Sartre’s play No Exit.

This was heady stuff in high school, and, as I look back on it, comically incongruous. Here I was, a curious but provincial teenager who lived on Oahu’s North Shore. Growing up, I woke to the mill whistle, spoke Hawaiian creole, and listened to the narratives of uncles who’d stop at our seawall to “talk story.” In 1974, our hardscrabble rural community was morphing into the surfing capital of the world. The hunky Hawaiian heroes of my childhood were now jockeying for waves with towheaded Californians. The field workers and taro farmers and fisherman were being supplanted by hippies from everywhere.

But here I was at Punahou, reading Sartre. While my French teacher was trying to press upon us the difference between the cool and colloquial pas mal and the ingénue’s fantastique!, my English teacher was urging us to decode terms like en soi and the pour soi and leading discussions about the hell that is “other people.” I couldn’t fathom what existentialists were talking about. And yet I was not immune to human cruelties — my parents had divorced, the confusions of adolescence were lingering, and I was a haole in a place of confusing racial dynamics. I was also struggling to make sense of an American adult world I dreamed of entering. That world was perhaps represented by my father, an Army lieutenant colonel just back from Vietnam and working at the Pentagon. (I would only recognize this as perhaps a definition of existential “absurdity” much later; at the time it just complicated my understanding of the American adult world.) My teacher in Ideas in Western Literature was a product of Williams College with an uncanny resemblance to my faraway father. He was more approachable than Dad and far more credible. This might explain why I threw myself into the reading.

Still, Sartre left me cold. I would spend the free period after class walking on campus, looking up at an achingly blue sky through the spreading canopies of ancient monkeypod trees, which in winter looked like lace doilies against the heavens. That was as close as I could get to absurdity. Lace doilies in Hawaii!

Then we read Camus. Thankfully, we didn’t start with his astringent novel The Stranger. It surely would have left me cold, too. Instead we read The Myth of Sisyphus. Camus’s idea of futility, the endless rolling of a rock up a hill — this I could grasp. It felt not unlike the workload of an overachiever, the rock standing in for the stack of books I carried back out to the beach each night, knowing I’d never complete the reading. Or the impossibility of repairing my ruptured family. Or of fitting in at my fancy school. The idea that there might be a kind of happiness, and freedom, in recognizing futility appealed to me. Still, absurdity? I couldn’t get there.

I struggled with existentialism not just because I was a young woman living in Hawaii, a striver, and, temperamentally, an enthusiast, but also because I was an Episcopalian. I believed in faith, hope, and charity. And in the possibility of redemption.

The Myth of Sisyphus was just a preparing of the ground, a warm-up for The Plague, Camus’s treatise about the suffering visited upon an Algerian town in the 1940s when a mysterious plague strikes and its citizens must contend not just with fear and sickness, but with paradoxical ideas of love, exile, and suffering.

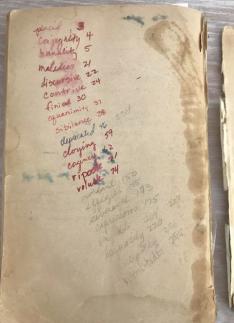

I’m not sure where I found the patience to plow through the first 250 pages, which lacked the usual devices of a novel. But I was a serious student, and I did want to please my teacher. I remember reading The Plague as a slog through dense paragraphs, studded with words I’d write on the endpapers, with page citations, intending to transfer them onto my SAT word list. But then I reached Part V, when the threat of plague recedes and the interpersonal drama intensifies.

A physician, Dr. Rieux, is the narrator and protagonist (he would refuse the word “hero”), and much of the book consists of our making rounds with him and his cadre of volunteers. We are not spared scenes of suffering, or images of coughs that rumble in the chest, fevers that uprush, and paroxysms that precede death. Amid the scenes of infirm patients and endless infirmaries and municipal streetcars carrying bodies to large pits, where they are dumped and covered with lime, there is one scene that leaves an indelible imprint. Dr. Rieux and Jean Tarrou decide to cement their doomed friendship by taking a swim in a Mediterranean that is off limits to most:

“They saw the sea spread out before them, a gently heaving expanse of deep-piled velvet, supple and sleek as a creature of the wild. Slowly the waters rose and sank, and with their tranquil breathing sudden oily glints formed and flickered over the surface in a haze of broken lights. Before them the darkness stretched out into infinity.... They undressed, and Rieux dived in first. After the first shock of cold had passed and he came back to the surface the water seemed tepid. When he had taken a few strokes he found that the sea was warm that night with the warmth of autumn seas that borrow from the shore the accumulated heat of the long days of summer. The movement of his feet left a foaming wake as he swam steadily ahead, and the water slipped along his arms to close in tightly on his legs. A loud splash told him that Tarrou had dived. Rieux lay on his back and stayed motionless, gazing up at the dome of sky lit by the stars and moon. He drew a deep breath. Then he heard a sound of beaten water, louder and louder, amazingly clear in the hollow silence of the night. Tarrou was coming up with him, he now could hear his breathing.”

The sea! Two friends swimming side by side, “with the same zest, the same rhythm”! They are isolated from the world, free of the town and of the plague, conscious of being, for a brief moment, “perfectly at one.” It gives them both a “strange happiness.” Sisyphus, too, had been possessed of such a happiness, which Camus now describes as “a happiness that forgot nothing, even murder.”

The friendship never has “the time to enter fully into the life” of either man. Tarrou succumbs to the pestilence. Rieux tends to his compatriot as Tarrou suffers through burning skin and raging thirst and visceral cough and ugly abscesses and ganglia embedded in the joints “like lumps of iron.” And weariness. Tarrou finally dies, never relinquishing his hard-boiled desire for the truth from his doctor-friend and never giving up on his saintly “quest for peace by service in the cause of others.”

The swim is the most beautiful scene in the book, but then there are the moments when Camus — or his proxy Rieux — reflects on the faces of love. On the affection between Mme. Rieux and her son the doctor; on the passion of journalist Raymond Rambert for his wife, from whom he is separated; on the unrequited love of a town clerk, Joseph Grand, who obsesses on the wife who left him; and, very sparingly, on the doctor’s feelings for his own wife, who is away in a sanitorium and who, he knows, is dying.

“A loveless world is a dead world,” the narrator says. I was reading all this at an age when romantic love was the only thing, and I longed to know its pleasures. But here I was given something else to latch onto, a kind of deep sympathy, what the Greeks call agápē, what Rieux calls a love that defies “the words befitting it.” On the night of Tarrou’s death, Rieux reflects on “having known plague and remembering it, of having known friendship and remembering it, of knowing affection and being destined one day to remember it.” This is the idea that changed me when I was 16.

___

As the novel coronavirus descended upon us, I found my ragged Modern Library College Edition standing in the bookshelf next to works by Umberto Eco, Eduardo Galliano, Octavio Paz, Natalia Ginzburg, Ernest Hemingway, and Adrienne Rich. (The random list of a lit major who never studied philosophy nor received a proper syllabus.) The Scotch tape holding the cover of the book together has failed; its once white pages are now the color of pale ale. Somewhere along the way the book got wet, and some of my teenage scribblings have become watercolor blobs. My SAT vocabulary words still cascade down the endpaper. Layered over my initial responses are notes from when I reread the book in my 20s. Tucked into Part IV is a handwritten copy of the Prayer of Saint Francis, from that second reading. The prayer reminds me of how I was still struggling to take in Camus without turning my back on my desire to be “an instrument of Thy peace.”

The rereading today is not homework given by an inspiring teacher, an attempt of an earnest teenager to digest Ideas in Western Literature. I have absorbed those vocabulary words into my lexicon, so that the experience is less of a slog. And I’ve learned that the narrative is considered an allegory about Facism or the French resistance to the Occupation. But this is not an intellectual exercise. I look at the scribbled notes of a young mind trying to conjure unimaginable horrors and marvel that all I have to do now is turn on the TV.

The book offers brilliant commentary on our response to the coronavirus. We have, in place of French prefects and a health committee in denial, a president who cannot embrace science and who relies on the rhetoric of a con man. We have corrosive politics and collapsed institutions. We have scammers who hoard hand sanitizer and spammers who peddle thermometers. But we also have state governors who are courageous enough to speak truth to power and magnanimous enough to grant each of us a place in the national family. We have journalists willing to ask tough questions and spiritual leaders shedding light on the human condition. We have people getting sick, suffering, dying. We have truth tellers like Tarrou and healers like Rieux.

In the week after our leaders warned us of very tough days ahead, I noticed that old friends started calling. My childhood best friend, whom I’ve barely seen in 15 years. A friend I consider my adopted brother but see only a few times a year. Colleagues on the East Coast. An estranged friend from my 20s and another from my 40s. The conversations have been long, urgent, and glorious. One of those estranged friends is working to place homeless seniors. I leave a box of oranges from our tree on the stoop for her and wave from the yard when she retrieves them. Each fruit is a kind of homely joke: misshapen, either too big or too small, with its own mixture of sweet and sour — ripe with possibility, bursting with food for the soul.

After some strained phone calls, my 86-year-old mother in Hawaii, who resisted self-isolation, emailed, “I’m doing little projects and thankful that I have ocean to look at and listen to, also yard to walk around in.” She sewed three face masks this week and is forwarding Morning Prayer messages from her priest. We’ve discovered the merits of FaceTime and Zoom, which allow her to read lips, enhancing the connection between us.

I finished The Plague this morning. The final pale-ale pages make me weep. And they bring strange comfort. I’m not enough of a philosopher to parse out all the ideas and not enough of a poet to find words for the feelings. Yet one doesn’t have to be a philosopher or a poet. For Rieux, after all, the only means of fighting a plague is “common decency.” A modest bar, one we can all reach. He says that what we humans learn in a time of pestilence is “that there are more things to admire in men than to despise.”

I keep coming back to the thing that Rieux says we cannot name but which I think of as agápē — the spiritual or selfless love that also encompasses affection, fondness, warmth, and protection. The Latin cāritās (charity, in the sense of benevolence and generosity) is there, too. These are intangibles, but ones that help us gird against hopelessness.