But privately, Dunbar bemoaned the way Howells pigeonholed him as a writer and the literary kingmaker’s inability to evaluate his work beyond his narrow perspective on race. The review by Howells, who also became editor of The Atlantic Monthly, reeked of paternalistic racism. He ignored the accomplishments of other Black writers such as Frederick Douglass, Phillis Wheatley, and George Moses Horton while arguing the race had yet to make “its mark in his art.” He exotified Dunbar’s physical attributes such as his “wooly hair” and “thick outrolling lips.” Worse yet, Howells’ heaped far greater praise on the parts of the book that exemplified Black dialect while ignoring Dunbar’s artistic mastery of standard English in his poetry.

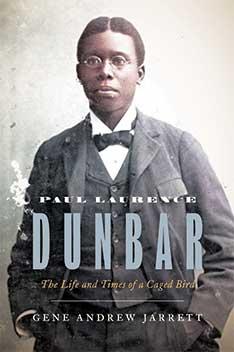

The biography Paul Laurence Dunbar: The Life and Times of a Caged Bird, by Dean of the Faculty and English professor Gene Andrew Jarrett ’97 offers a detailed account of Dunbar’s private struggles as he was being outwardly celebrated as the “poet laureate of his race.” The caged bird refers to a 1899 poem by Dunbar called Sympathy that chronicles the travails of a bird that is trying to spread its wings and seek freedom while living inside of a cage — a theme picked up by lauded poet Maya Angelou nearly a century later. Dunbar’s last stanza alludes to his desperation to break free from the cultural limits placed on him:

I know why the caged bird sings, ah me,

When his wing is bruised and his bosom sore,—

When he beats his bars and he would be free;

It is not a carol of joy or glee,

But a prayer that he sends from his heart’s deep core,

But a plea, that upward to Heaven he flings—

I know why the caged bird sings!

Jarrett uses the caged bird as an anchoring metaphor for the life story of Dunbar, who struggled to overcome the legacy of a tough childhood and the societal perceptions that were imposed on him as a Black artist. “This is the kind of thing that we all face. There are ways in which you view yourself but there are also ways in which people view you,” says Jarrett. “Part of life is [figuring out] how do you synchronize the outside perception of you and your internal perception?”

Jarrett timed the June release of his book to mark the 150th anniversary of Dunbar’s birth but his scholarly interest in the poet’s life dates back far longer. Jarrett first studied Dunbar’s writing as an undergraduate and later – at Brown University – as he was writing his dissertation. His first book, Deans and Truants: Race and Realism in African American Literature — based on his doctoral work — probed the lackluster reception faced by Black writers who don't focus on race. In his second book, Representing the Race: A New Political History of African American Literature, Jarrett examines the political value of African American literature. Now in this third book, Jarrett uses Dunbar’s personal letters to show how the writer privately grappled with oppression and his own demons as he sought and obtained professional success in the eyes of white critics.

“What I've tried to do is to indicate the ways in which he really wanted to be a successful writer. And he was trying to understand the literary world but he had to work out certain ideas in his conversations with his confidantes,” Jarrett says. In his letters “what you find is an unveiling of the raw emotions and thoughts that he had about his success.

After Howells’ review, Dunbar’s career took off. He published multiple books of poems, novels, essays, and short stories that spanned genres and subjects. In 1897, Dunbar traveled to London, where he recited his work before elite crowds. Upon his return, he took a job at the Library of Congress. Dunbar’s most popular works were often written in the dialect associated with Black people in the antebellum South.

“Literature authored by mainstream audiences most excited mainstream audiences when it portrayed the stereotypical dialogue of slaves, which became the mythical object of white nostalgia once the Emancipation Proclamation liberated 3 million slaves in 1863 and portended to the metaphorical disappearance of their racist caricatures and vernacular,” writes Jarrett.

The seeds of Dunbar’s success and personal failings can be traced to his upbringing in Dayton, Ohio. He was born on June 27, 1872, to Joshua Dunbar and Matilda Murphy, two former slaves from Kentucky who had a troubled marriage. The senior Dunbar struggled with alcoholism and abandoned the family for long stretches of time before they finally got divorced. Dunbar attended the mixed-raced Central High School, where he received a rich classical education focused on Greek, Latin, physics, algebra, and other subjects. While there Dunbar, along with a white classmate, Orville Wright who later invented the airplane with his brother, also published a short-lived newspaper for the Black community called The Tattler. “No other time was more important to Paul’s growth as a writer – in terms of his pure talent to write literature, and his practical knowledge to recite and publish it — than his time at Central High School,” writes Jarrett.

Jarrett also chronicles Dunbar’s budding romance and subsequent marriage with Alice Ruth Moore, a noted Black writer in her own right. Dunbar wrote his first letter to Moore after seeing her photograph in Monthly Review, a Boston-based magazine. In their letters, they swapped writing samples and intimate details about their creative process amid flirtatious asides. Both Moore and Dunbar rejected the idea that African American literature had to use racial dialect or even talk about race at all. “I too believe that a story is a story and try to make my characters ‘real live people,’ ” Dunbar wrote to Moore in one letter.

Their relationship was marred by significant turbulence often fueled by Dunbar’s indiscretions with other women, drunken misbehavior, and violent physical abuse against Moore. The couple separated just four years before Dunbar died of tuberculosis in 1906 at the age of 33.

Since his death, perspectives on Dunbar’s work have evolved from those expressed in that first review by Howell.After the dawn of the Harlem Renaissance movement in the 1920s, Dunbar’s work was challenged by some Black artists and scholars, some of whom were his contemporaries. Civil rights activist and writer James Weldon Johnson, for instance, argued that Dunbar promoted the same kind of Black caricatures you might find in a degrading minstrel show. Black artists that came after Dunbar such as Zora Neale Hurston and Claude McKay reimagined Black vernacular. Along with the rise of the Black Arts Movement of the 1960s and ’70s, more scholars began closely reading Dunbar’s work and recognized more nuanced portrayals of Black people in his writing, says Jarrett.

“If you look more deeply, he imbues those Black dialect speakers, if they are Black, with a certain kind of humanity and complexity in ways that were not picked up probably during Dunbar’s own time,” Jarrett says. “As we have built up the tools of analysis to look at his work, we are seeing even more the sophistication of his writing.”