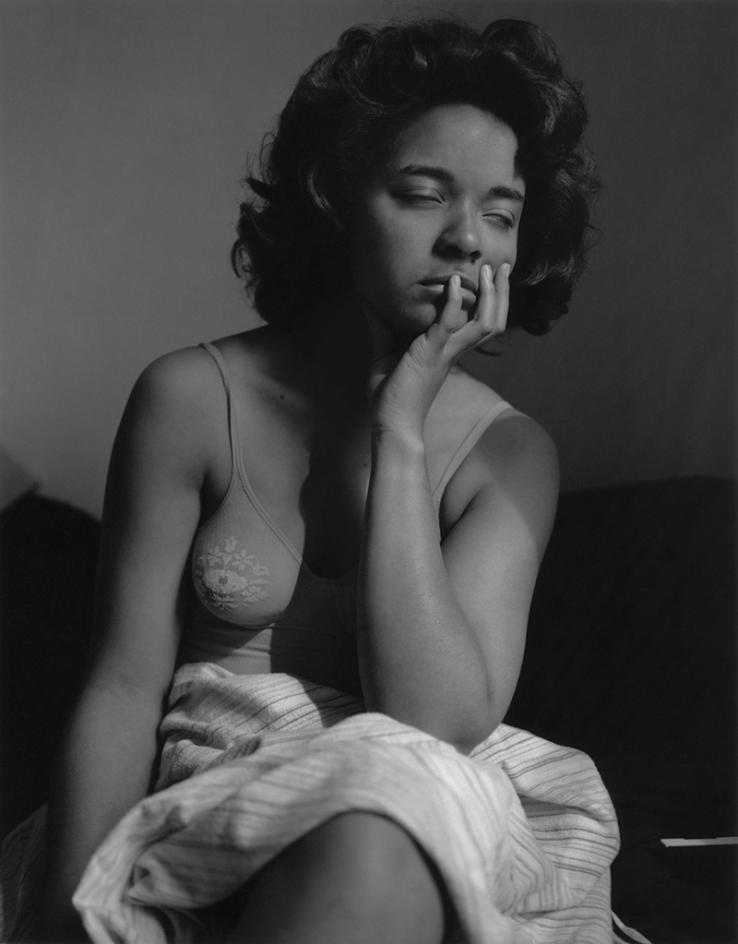

For her senior thesis, Carla Williams ’86 mounted an exhibition of 74 photographic self-portraits. Her adviser Emmet Gowin remembers the show as perhaps the best thesis he advised in his 36 years on the Princeton faculty. “There are images here which are painful, fearful, proud, strong, humorous, sensuous, tender and even faintly frightening,” Gowin wrote in 1986 of the body of work Williams produced in her dorm room — a 1901 Hall single her senior year — with a secondhand Speed Graphic 4x5 camera.

Williams went on to craft a career as a scholar, teacher, and merchant of photography, but her college work didn’t gain a wider audience until it was published last year as a monograph with the title Tender, which later won the First PhotoBook award at the 2023 Paris Photo-Aperture PhotoBook Awards. Shortly after publication last fall, the images were exhibited once again — for the first time since her Princeton thesis show — at Higher Pictures Generation, a gallery in Brooklyn, New York.

Williams didn’t take art classes in high school in Los Angeles, where she grew up, but she enjoyed a course in Italian Renaissance art and applied to take a photography course the next semester.

“I had an interview with Emmet,” Williams remembers, “and from the moment I stepped into the basement of 185 Nassau Street, I knew. It was the smell of it, the sound of it. By the time I got to the classroom and office area, I wanted in.”

Williams started making self-portraits in her first photography class, and she initially focused on the genre for practical reasons. “I wanted to learn how to use the large-format viewfinder on the camera,” she says, “so I thought, ‘Let me use myself as a subject until I get up to speed.’”

But there was a deeper rationale for her project. “I was a young Black woman,” she says. “I was curious to see my likeness. I was taking Peter Bunnell’s History of Photography course, and I wasn’t represented in what I was seeing.”

Williams did take some of the works she studied in the course as models, including Alfred Stieglitz’s portraits of Georgia O’Keeffe and Edward Weston’s portraits of female nudes. She says she was also influenced by images of naked women in the collection of Penthouse and Playboy magazines her father kept in their home.

“Once she began to take self-portraits, her personhood, her sensibility started to really come out,” Gowin says of Williams. “It was totally uncommon in that era for women to take themselves as the central subject of everything they did. She was able to sustain a level of invention and beauty that’s still astonishing.”

And, he adds, her “willingness to accept chance and imperfection” in the photographs themselves, “to take what you get and make the most of it, is a really strong characteristic. It made her work more personal.”

Williams earned an MFA in photography from the University of New Mexico after graduating from Princeton, but she never marketed her work aggressively. She was uncomfortable with the commercial aspects of the art world, and, she says, “In the early 1990s, Black photographers were only just starting to be shown.”

Instead, Williams worked as a curator of photography, first at the Getty Museum in Los Angeles and then at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York. In 2002, she co-authored The Black Female Body: A Photographic History, a foundational work on the topic, with curator and scholar Deborah Willis. Williams taught photography for five years at the Rochester Institute of Technology, but in 2014 she moved to New Orleans to open a store featuring fine and decorative arts by Black artists and designers.

“There was no conscious moment of feeling done” as a photographer, Williams says. “It just wasn’t my focus. At that point I had no plans to pursue photography.”

After Williams had to close her store at the start of the pandemic, she scanned all of the photographs in her house, created a website, and put some of the images on her store’s Instagram page. One of her customers, the photographer Paul Mpagi Sepuya, noticed the self-portraits on Instagram and recommended them to publisher Paul Schiek, who suggested Williams put out a book of her work.

Through Schiek, Williams was introduced to the gallery Higher Pictures, which proposed restaging Williams’ senior thesis exhibition. “It delighted me that someone else was thinking about the show besides me,” Williams says. “I had my trepidations about some of the images holding up, but I trusted the gallerists.”

Gowin came to the November opening of the show, which was composed mostly of original prints from the thesis exhibition with the same presentation and sequencing. “The first thing we said was that it was better than we had thought,” Williams says. “It was a revelation that it had stood the test of time. I was quite delighted.”