Hollywood is sorority racist. It’s like, “We like you, Rhonda, but you’re not a Kappa.”

— Chris Rock

Today, our old friend here at History Central, the Law of Unintended Consequences, gets a severe workout. This time it’s disguised as the Tariff Act of July 14, 1862, one of the myriad ways in which the United States government attempted to raise funds for the wildly escalating Civil War. Wise prognosticators (oxymoron alert) initially had thought it would last weeks; a year later, the Union had 700,000 men under arms and needed cash. The effects, in conjunction with added tariffs of the prior year, were global; imports from booze to steel to seeds were hit steeply, and foreign businesses relying on exports to America were shaken. In the case of Lazarus Morgenthau and his family in Mannheim on the Rhine, it almost instantly crippled their cigar-manufacturing business, and by 1866 he felt he had no option but to emigrate to the postwar United States.

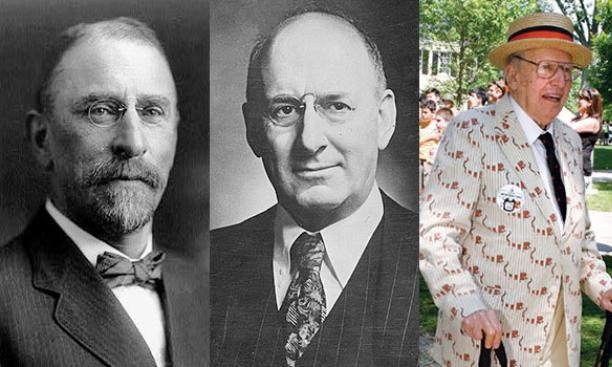

His ninth child, Henry, who was 9 years old when he arrived here, followed a time-honored path for immigrant children in New York City; after schooling at P.S. 14 in Manhattan, he attended City College, then cemented his future with a law degree at Columbia. He practiced law, made a serious fortune in real estate, and gradually was drawn to politics. He met Woodrow Wilson 1879 in 1911, was enormously impressed, and donated heavily to his campaign for president. Upon election, Wilson gave Morgenthau the challenge of the ambassadorship to the hostile Ottoman Empire; when World War I began the following year, Morgenthau’s desk in Constantinople became the clearinghouse for any correspondence from the Allies about the Turks, with whom they were at war. When the Armenian genocide began in 1914, he was immediately made aware through his legations, and objected to the Turkish government in every way he could devise, up to initiating a campaign in the United States that raised the then-astronomical sum of $100 million for Armenian relief. Morganthau co-founded the American Red Cross, and remained an honored philanthropist and diplomatic advisor to Democratic politicians for the rest of his 90-year life.

His son, Henry Jr., befitting his well-to-do father, prepped at the Dwight School, then, intriguingly, studied agriculture at Cornell. He initially met Franklin Roosevelt because they both grew Christmas trees at their nearby farms on the Hudson. In 1929, Roosevelt was elected governor of New York, and Morgenthau was named chair of the state agricultural advisory committee. Four years later, with the Depression in full swing, Roosevelt as president initially named him governor of the Federal Farm Board, then in 1934 secretary of the treasury, where Morgenthau served until Roosevelt died 11 crisis-ridden years later. He fought organized crime; he implemented the financial side of the New Deal; he financed the Lend-Lease program that kept Britain alive in 1940 and so became central in World War II strategic planning; he was elected president of the Bretton Woods conference that revolutionized international finance in 1944.

His son, Henry III, today 99 years old, graduated from prestigious Deerfield Academy in 1935 and headed off to Princeton with many of his prep-school classmates as a member of the Class of 1939. He majored in art and archaeology, won his varsity “P” in cross country, designed sets for Theater Intime, joined the editorial boards of both the Nassau Lit and the Prince, and worked summers helping disadvantaged kids at the Princeton Summer Camp, which recently had moved to its new home in the mountains of Blairstown. His grandfather, at 80, was an internationally known diplomatic authority; his father was the second-ranking cabinet officer in the United States. Through them, Henry III was invited to visit Albert Einstein at his Princeton home.

And in February 1937, Morgenthau interviewed in his room like the other sophomores, but received no bids during bicker; apparently his record, connections, and personality were insufficient to make him “clubbable” anywhere on the Street. A non-observant Jew, he and four of his 11 Jewish classmates joined no club at all in an era when that translated to social death.

Two months later, University President Harold Dodds *1914 and Mrs. Dodds hosted a dinner in honor of Henry’s visiting parents at Prospect.

As the University’s Jewish community and its friends meet this month to celebrate 100 years of Jewish life here, we dwell for a bit on how an entire institution can go badly astray – for decades – when a few key leaders find pettiness and priggishness empowering, and nobody else raises a finger to object. As Jewish men rose, along with a vast range of other immigrant people, to positions of importance and power in the country early in the 20th century, Princeton developed a ludicrous quota system, enhanced it in complex ways, and continually insisted it did not exist. While it coincided with the overtly racist exclusion of blacks from the campus (except in servile roles), it was not the same thing at all. African-American people were generally dismissed in toto as unprepared for a serious college experience, but the stereotyping of Jews was that “they” were too smart, too bookish, not well-rounded, habitual loners with no sense of institutional loyalty, i.e. had no school or team spirit. So the admission system was simultaneously academically rigorous or anti-intellectual, depending on your racial and ethnic background. Princeton instead was looking for the “well-rounded boy” – a term that was a mantra from the 1920s into the ’60s – and Jews were thus generally presumed to be unqualified. Of course, a simple chat with Henry Morganthau III would have rendered that laughable, except that his time at Princeton coincided with Kristallnacht in the Third Reich, so anti-Semitism was hardly a laughing matter.

To compound the weirdness of this story, it begins with Wilson, as president of Princeton, firmly on both sides of the discriminatory fence. Profoundly racist toward blacks, his desire for a far more intellectually rigorous University involved essentially every facet of campus life, from attracting bright students from a wider range of schools to overhauling the faculty to attempting to break up the social hegemony of the eating clubs. The first pointed the way toward bright immigrant public-school children; the second to hiring Princeton’s first Jewish professor, Horace Meyer Kallen in English in 1903; but the third only hastened his ouster as president, since the well-to-do trustees sided with their beloved clubs. As the University implemented Wilson’s classroom strategies in pieces over the next few years, accomplished Jewish students became more plentiful, although the Street just became more insular and powerful. The first communal Shabbat observance on campus (the centennial being celebrated by this month’s conference) was in 1915. The University even recognized its first two Jewish honorary-degree recipients: Rufus Isaacs, the Earl of Reading and British ambassador to the United States, in 1918; and then in 1921, Albert Einstein, much of whose crucial scientific support in the United States had come from the Princeton faculty assembled initially by Wilson.

So wait now: How, between 1921 and 1937, did public adulation of a revolutionary mind morph into the hosing of the accomplished son of the secretary of the treasury? It’s a tale that involves refined layers of ethnic xenophobia and irrationality that (while common among institutional peers at the time) reached and remained at the height of hypocrisy, as successive perpetrators denied discrimination of any sort.

Next time: Selective admission and the clubs’ stranglehold on social life combine to marginalize Jewish students at Princeton for decades, and Dirty Bicker finally leads to permanent change.

Gregg Lange ’70 is a member of the Princetoniana Committee and the Alumni Council Committee on Reunions, an Alumni Schools Committee volunteer, and a trustee of WPRB radio. He was a recipient of the Alumni Council’s Award for Service to Princeton at Reunions 2010.