“[Baseball is] supposed to be hard. If it wasn’t hard, everyone would do it.

The hard is what makes it great.”

— Jimmy Dugan, A League of Their Own, 1992

I am embarrassingly enamored of George Smiley. One of the great symbolic characters of 20th-century literature, he towers over the Cold War the way Hercule Poirot dominates the desperate, sinister Europe of the 20 years between the World Wars, or Sherlock Holmes the High Victorian Era. As a child of the television age, I will freely admit to being influenced by the intriguing portrayals of the three by the British actors Alec Guinness, David Suchet, and Jeremy Brett, but the existential truth stretches far beyond them. A certain tell: Each and every time any of them interacted with higher reaches of the government, bad things happened. Secrets spilled, lives were shattered, countries fell. But you will note one fascinating change between the reigns of Holmes and Poirot, in which consulting detectives were glimpsed in the gossip columns, and that of Smiley, who carried on his battle/obsession with Karla in the depths of for-your-eyes-only anonymity. Alone among the three, Smiley legitimately can be acted by a range of physical types, in large part because his description via the otherwise meticulous John le Carré is so forgettable itself. In fact, it’s crucial to Smiley’s success as a profoundly forgettable superspy.

There is yet another attendant aspect to Smiley that draws us here: his social ineptitude. While Holmes and Poirot have abundant asocial reasons for their state of confirmed bachelorhood, Smiley once gave domestic bliss the old college try (stiff upper lip and all that), and with a titled lady to boot. Not only did the marriage self-immolate, leaving Smiley a mess, but it led to the deaths of dozens of brave foreign agents in the bargain. The message is hardly subtle. These obsessed seers, these men of higher sensitivity and understanding of the mechanics of life, are achingly believable, even sympathetic, in their ineptitude when approaching its emotions.

Although it was a great idea, I was actually quite surprised to read of the current exhibit on Moe Berg ’23 at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Within the permanent exhibition on the history of the game, which occupies an entire museum floor, various in-depth features attach like sidebars: a history of the Negro Leagues and their spectacular stars operating in the shadows and videos of Carlton Fisk and Bucky Dent to placate and terrorize Red Sox fans, for example. Berg’s, which in a masterstroke of symbolism occupies little floor space but a huge amount of intellect, abuts the wonderful exhibit on the AAGPBL, the women’s major league of the 1940s and ’50s, which includes clips from A League of Their Own, the excellent film directed by the late Penny Marshall.

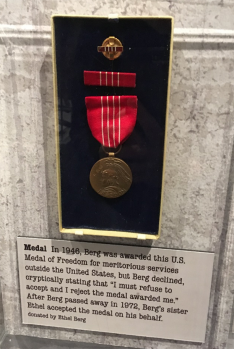

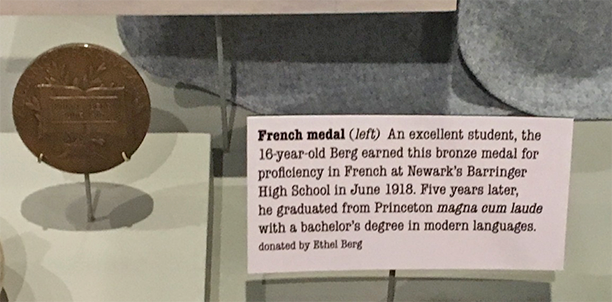

The same, alas, was not true of The Catcher Was a Spy, last year’s movie based on Nicholas Dawidoff’s wonderful book on Berg. Although a couple of costumes from the film visually enliven the layout, that is not why you go all the way to Cooperstown, N.Y., when you can simply stream the movie. I’ll tell you why I went: I have never seen a Medal of Freedom in person before. Awarded to Berg and a smattering of other behind-the-scenes civilian heroes of World War II in 1946 by Harry Truman, the simple but arresting bright red decoration encompasses two great themes of Berg’s life: the huge depth of substance flowing below the surface of his journeyman-ballplayer persona, but also his growing disconnect from the mainstream of daily American existence, clearly apparent when he initially refused the award. (His sister reclaimed it for him following his death in 1972.) Whether the refusal was from modesty or from his displeasure with the CIA for not taking him seriously, even after the critical government war service with the OSS that Truman was honoring, is not clear — and may not have been to him — but his lack of fit in the culture over the next 26 years clearly began around that time.Rather than highlight the movie, the exhibit takes a documentary approach that contrasts it nicely to the entertainment that surrounds it throughout the Hall (e.g. the original San Diego Chicken costume) and meticulously uses key memorabilia thoughtfully collected and donated to the Hall by Berg’s family, including the Medal of Freedom. There are his mask and pristine jersey from his 1930s trip to Japan, a gift cigarette lighter from the Meiji University baseball team, and on and on, even through classified documents from WWII. Additionally, the Hall has put a large selection of Berg’s memorabilia online in its ever-improving digital collection, which beyond the unique history is just fun to peruse, such as the wonderful symbolism of his contract with my Chicago White Sox: the perfect coupling of a hitless catcher with a hapless franchise.

But to return to the business at hand, it is stunning to look at George Smiley and see reflected back Moe Berg, and vice versa. Brilliantly educated, linguistically superb, callers of signals, compulsively alert, they wend unremarked through youthful adventures (in Berg’s case, his famed baseball trip to Japan, with possible surreptitious photographs of war materiel) into restive middle age namelessly fighting the global enemy, into seemingly never-ending friction with the bureaucracy thereafter. And in any meaningful social sense, both remain forever awkwardly outside the culture they are striving to protect at any cost.

When trying simultaneously to educate a few thousand brilliant people on campus, this can sometimes be forgotten or at least momentarily obscured, always to the detriment of everybody. Within the current college generation’s hang-ups on privilege and social slights, we must be careful to understand that inevitably some students aren’t social butterflies and/or don’t wish to be and/or couldn’t be in any case, and they have a fully legitimate place here.

The Princeton that was welcoming to Alan Turing *38 and John Nash *50, two legitimate geniuses of the 20th century who were demonstrably far off the social norms of their day in the best of times, should instruct us all. Indeed, Nash’s survival through full-blown mental illness all the way to a Nobel Prize indeed honors his wife Alicia, but as much his colleagues in the Princeton community. Without a similar understanding line of defense, Turing’s prosecution in Britain and tragic death at 41 stand in grim opposition.

Back in the day, when all Princeton’s clubs were selective and alternative undergrad social existence was anemic-cum-nonexistent, the concept of a viable social alternative (the buzzword du jour) arose to emphasize the idea that, as the saying went, there are different strokes for different folks. My resulting involvement in helping start Stevenson Hall was one of my more fulfilling adventures. Some wag, based on its open signup, called it Random House, and we gleefully adopted the tag in the spirit of John Wheeler appropriating the derisive term “Black Hole.” No one yet calls the Street perfect, but it’s sure not the same place now.

In college, Moe Berg had the camaraderie of the baseball team to support him, but you wonder, when while playing second he changed to signals in Latin if the opposition had runners on base, he may have felt a bit outside the mainstream.

We seem to be at a moment in time when the bullies are ascendant. Through Holmes, Poirot, Smiley, and Berg and his Medal of Freedom, we see that when we use our talents in the service of those of us who may require it, the bullies fade away as they always do, and we can all return together to using our various strengths to improve our world. Our joint medal of freedom, as it were.