“Don’t give up! I believe in you all.

A person’s a person no matter how small.”

— Horton Hears a Who, Dr. Seuss, 1954

The recent opening of the inspirational home complex of the Lewis Center for the Arts — for those who haven’t made it back to campus, the magnificent rehearsal halls are almost on a par with the world’s most stylish Wawa, adjacent — brings to mind an aspect of writing Princeton history I feel almost constantly but rarely mention: I could spend the entire column in every issue of Your Favorite Periodical discussing nothing but volunteer alumni and their impact on the University and, very often, the greater world beyond. Peter Lewis ’55 and his living legacies of spaces both creative for the artist and contemplative for the scientist are but a trigger for recalling a flood of examples that pervade the campus, the students, and very tangibly the wider intellectual world in which we all reside. I can’t think of a time I more enjoyed writing a column than in detailing the extraordinary life of Bill Scheide ’36 and his singular achievements in scholarship and philanthropy; the idea the most valuable single gift ever made to Princeton was a hand-assembled collection of human aspiration and achievement is an example each of us can take to heart. Our unique value, to ourselves and incidentally to Princeton, is in who we are and what we can imagine, far beyond whatever we can toss into Annual Giving or a capital campaign. Scheide’s imagination as evidenced by his Bach collection or Peter Lewis’ by his transformative arts programs will shape alumni and influence of the University for many decades, and that’s something to consider far beyond the question of “donations.”

Which brings us to Santa Fe, long a staple of my cask list (which is like a bucket list for those whose priorities are influenced by fermentation), which I finally got to check off last spring on a wonderful sojourn through the desert, the adobe, and the thriving arts scene. Among the many creative museum spaces there is the Museum of International Folk Art, the very idea of which shows a sense of adventure with significant promise. Which is more than fulfilled by a single one of the thousands of handmade inspirations on display:

As you walk into the museum’s activity center, geared for peripatetic youngsters but sprinkled with art objects that would fascinate anyone with a sense of whimsy or curiosity, you walk by the human-size Mrs. Cow, familiarly known as Elsie, and Ray the Wolf, exemplifying a few dozen of the best (+/-) aspects of American dating and/or party-going. You’d swear Ray was about to reach into his coat pocket and pull out his iPhone with the eHarmony app preloaded. The center is named for the donor of the hilarious sculpture, whom you might guess to be a pretty refreshing personage. It’s called Lloyd’s Treasure Chest, honoring Lloyd Cotsen ’50, a great benefactor of the museum and, indeed, refreshing in the extreme.

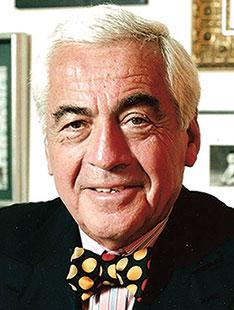

Cotsen, who died in May, insisted on being called an “accumulator” rather than a collector. Given the many tens of thousands of novel items he gathered from around the world, it would be difficult to argue strenuously with that, except that his eye and sensibility were so wildly creative. When he bought a kimono or a tea basket or a hand-illustrated pamphlet, it was both accessible, because he dealt primarily with everyday objects, and totally arresting as a reflection of his personality. In addition to funding exhibition space at the folk-art museum in the ’90s, he donated more than 3,000 objects from Elsie to pristine textiles from around the world.

The adjective seemingly attached to Cotsen’s name like Ray’s attention to Elsie was “transformative.” That applies to his career as much as his artistic sense: a Princeton history AB and Harvard MBA who served three years as a naval officer, he turned his attention to the ultimate in stereotypical commodity businesses: selling soap. His father-in-law had founded what became Neutrogena, and Cotsen embellished glycerin soap into a combination fashion and medical go-to brand that was worth almost a billion dollars to Johnson & Johnson in a 1994 buyout, after which his philanthropic donations began in earnest.

But he had been collecting, uh, accumulating forever, from baseball cards as a boy to woven Japanese baskets as a sailor in the Pacific to a world’s range of children’s books as his own kids became of reading age. And once bitten by the archaeology bug, he went on digs and began eying artifacts there, too; he ended up endowing the Cotsen Institute of Archaeology at UCLA (he lived in Los Angeles), and spent 20 years on the advisory board of the Princeton art and archaeology department. He founded and endowed the Cotsen Foundation for the Art of Teaching in L.A. as well. As his collections of the artworks of the common people became progressively larger and more remarkable, he spun them off to enrich viewers far and wide; Chinese hand mirrors to Shanghai, the Japanese tea baskets to San Francisco, the folk pieces to Santa Fe.

Meanwhile, his obvious fondness for alma mater stretched far, wide, and frequently. Beyond archaeology, he spent 14 years on Princeton’s board of trustees, he endowed professorships and fellowships, he founded the Society of Fellows in the Liberal Arts, he donated unique collected items to both the art museum and the library, where he also served on the Council of the Friends. But for purposes of considering his transformative nature (think Elsie and Ray), let’s focus on something beyond those.

Now, when I was an undergrad, everybody ended up in the Firestone reserve reading room all the time, since movable type had recently been invented but the internet had not. There were few women, and on that basis alone contemplation of children’s literature seemed a couple steps premature. The closest item there, I suppose, was Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams, which I think we can agree is not exactly the same thing.

At the same time, as you recall, Lloyd Cotsen was gathering up books. Throwing himself into the effort with his usual élan, he discovered great illustrators of the past, earliest versions of fairy tales and Beatrix Potter, medieval manuscripts, an entire universe of literary adventure beyond the grownup world. By the time Neutrogena was sold, he had 40,000 volumes of children’s literature (and presumably some serious storage bills) assembled in a unique confection that can probably teach us — and crucially, our kids — at least as much about ourselves as Freud and all his followers combined. The Cotsen Children’s Library, dedicated in 1998, is a world center for the study, understanding, and (huzzah!) enjoyment of an intentionally simplified but limitlessly complex vision of life: our very own infinite Hundred Acre Wood, if you will. And the enjoyment part comes most directly in the Bookscape (a magnificent double entendre if ever there was one), just the right size for juvenile readers to cuddle up with a good read, which has supplanted the former reserve reading room, substituting fun activities and young classics for old class assignments. When I was a student wandering ecstatically along the miles of shelves in Firestone, it never would have occurred to me that one weakness in the vast collection of wisdom was the sheer delight of a child; but anyone who can’t find memorable insight in Dr. Seuss, Harry Potter, or Collodi’s original The Adventures of Pinocchio probably shouldn’t be allowed in the big-girl books’ section either. At Cotsen’s death, his collection exceeded 100,000 volumes; to term it a unique gift seems a little grumpy somehow; perhaps supercalifragilisticexpialidocious might be better.

Princeton has had far more than its share of generous donors over the years, and they have created wondrous things for the University. But there’s something very special about the two titans of Firestone Library, Bill Scheide and his hundreds of astounding historical touchstones, and Lloyd Cotsen and his tens of thousands of flights of fancy, whose generosity has left us with parts of themselves that can guide us all the way from the nascent ebullience of Raffi’s Baby Beluga to the majesty of the Gutenberg Bible. The importance of these gifts and the years of loving toil they represent defies description, which is the very point: The meaning, unique to each person, lies in the cultural cornucopia they have left with us, to treasure and nurture in their stead. The Scheide Library and the Cotsen Children’s Library allow us to see ourselves, and demand that we expand our vision to the edges of our abilities and dreams, if only to honor their granting us the ability to do so. God bless them both.

Dei sub numine viget.