Religion or astronomy (Descartes or Deuteronomy)

It all started with the big bang

Music and mythology, Einstein and astrology

It all started with the big bang

—Big Bang Theory Theme, Barenaked Ladies, 2007

As we wander by the corner of the desktop that betrays my avocation as a physics junkie (somewhere loosely between a Trekker and a Ph.D.), we glimpse the spine of Probable Impossibilities by my really esteemed classmate Alan Lightman ’70, one of the more pleasant extremely brilliant folks you’re likely to run across. He’s a physics Ph.D. and writer (both fiction and nonfiction) with an almost unlimited imagination; it’s not for nothing his best-known book is entitled Einstein’s Dreams. In the case of Probable Impossibilities, musing solely on real science doesn’t limit him for a moment: He discusses why our wetware brains can generate abstract ideas, why such capabilities might have arisen (spoiler alert: creating reunion themes is not mentioned), the expanding universe, inflation theory, stuff like that. And so we inevitably turn to Alan for an early read on one of the current fun ponderables in all of science: What came before the Big Bang?

After having spent a quality portion of the 20th century arguing about first causes in the universe, a group of physicists formed behind astronomer Edwin Hubble’s observations and posited an actual starting micromoment in time in which all the mass/energy (the same thing, remember?) that we experience was gathered in a tiny dot, then blew. Why? We’ll get back to you. The brilliant minds who just knew that was silly slapped the pejorative name Big Bang on the idea, and proponent John Archibald Wheeler at Palmer Lab, among others, gleefully took the snotty slight and ran with it. The rest, as they say, is prehistory.

So, since you can’t write a doctoral dissertation on the accepted Big Bang anymore, aspiring physicists have moved on to the obvious: Where did the beginning of time come from? If that doesn’t sound weird to you, you might want to ask yourself why not. I am happy to hide behind Alan and his highly informed reading of the tumultuous state of the debate, which in essence says that since quantum mechanics allows wildly unlikely things to happen once in a great while, you don’t need a tangible cause, just an astoundingly unlikely event, maybe quantum tunneling. And those who theorize the existence of multiverses are in accord, since that fits their equations. Of course, maybe instead we’re just oscillating around the Big Bang, but how would we know because going the other way (backwards to us) looks forwards to the beings there. If any. Or not. Anyway, read Alan’s book.

And so we slide effortlessly over to The History Corner from the Maybe Not History Corner, and turn our gaze to the nearest thing Princeton has to a pre-Big Bang controversy, namely: Are William Tennent Sr. and his Log College the trigger for the College of New Jersey in 1746, or were they simply in the vicinity when it happened?

“The Log College?” Really?

William Tennent was born in 1673 in Ireland, so came of age when the Church of England was clamping down on Oxbridge education for all non-adherants. So he went to Edinburgh (sound familiar? Think Witherspoon and McCosh), was ordained in the Church of Ireland, and married a Presbyterian preacher’s kid for good measure. They brought their family of five children to Philadelphia in 1717 or so, and Tennent was accepted by the Presbyterians after publicly renouncing most of the polity of the Anglicans, to include everything from top-down governance to fussy orders of service. This was just in time for the split between the Old Side (traditionalist) Presbyterians and the New Side (revisionist, highly personally oriented) believers; they fought over just about everything operational, from churches imposing local taxes on the populace to the requirements for ministerial education. The Oldies felt that only weighty, complex education was worthy of recognition in the pulpit, so accepted only European or Harvard or Yale-trained applicants for ordination. This led to a gigantic shortage of ministers in the Middle Colonies, where new towns and churches were being established almost by the day.

The Tennents, with plenty of Old World ministerial experience to fall back on, felt that was hooey. Anybody bright and inspired, in their view, could be taught the Bible, theology, and preaching if challenged with it, and that could be done locally by inspired teachers. This not only put them on the cutting edge of the New Siders, but as leaders of presbyteries that desperately needed local ministers and circuit riders. Financial backing (including donated land) thus came to the fore when Tennent decided, on top of his clerical duties in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, to open a school for the education of ministers in 1726. It existed hand-to-mouth for eight years, then in 1735 moved to a new rough building across the road from his home in Neshaminy, and along the way acquired the derisive term Log College (remember the “Big Bang,” physics fans?), perhaps by those who thought Oxford more aesthetically pleasing. This coincided with the flourishing of the First Great Awakening, with inspired ministers traveling the colonies preaching calls to Christ and a personal relationship with God, smack in the wheelhouse of the New Siders being educated at Neshaminy. At the center was charismatic young Englishman George Whitefield, who first visited Philadelphia in 1739, just in time to come within the spell of Tennent, his students, and their new presbytery of New Brunswick, which effectively created a giant new mission area from Staten Island to the Poconos to Trenton. This group, in defiance of the Philadelphia Synod (their HQ) were ordaining and calling Log College graduates to the ministry without further examination, which the big-city Old Siders refused to do. Whitefield preached tirelessly in towns large and small, and the energy of the movement enlivened many new congregations plus other local seminaries to fill the resultant clerical demand, in Faggs Manor (headed by Log College alum Samuel Blair) to the west, in West Nottingham (under Tennent-trained Samuel Finley) on the Maryland border, and in Pequea (led by Robert Smith, a student of Blair), far removed on the Susquehanna.

As Tennent turned 70 he began to shed duties, and the Log College began to wind down. His students spread throughout the presbytery and beyond, 18 or 20 of them in the 20 years of the college’s existence. In addition to Blair and Finley, there were his four sons Gilbert, William Jr., John, and Charles; John Blair, John Redman, and a dozen or so others; recordkeeping was not their strong suit.

The elder William Tennent died on May 6, 1746 (along with the Log College, for practical purposes), five months before the initial charter was granted by John Hamilton to the College of New Jersey. An activist ministerial group from the New York Synod had become fed up with the Old Side fussbudgeting at Yale and Harvard, and felt a new institution was their only way out. The charter called for 12 trustees, and named seven: six Yalies, including prime movers Jonathan Dickinson and Aaron Burr Sr., and one Harvard man. They in turn chose the other five, based on their perception of need: tellingly, four from the Log College, Gilbert and William Tennent Jr., Finley and Samuel Blair, and Yalie Richard Treat, William Tennent Sr.’s devoted supporter for many years. Finley even became College president after the first four died in office over 15 years; his predecessor Samuel Davies had been educated under Blair at Faggs Manor. The Tennent brothers even traveled to Britain in 1753 to raise money for Nassau Hall.

So was Oct. 22, 1746, really Princeton’s Big Bang, or an echo of it, or the beginning of hyperinflation, or what? Well, the new College of New Jersey was explicitly nonsectarian and offered a very different curriculum, its liberal arts and sciences leading to a much broader student populace and career paths among its alumni. Meanwhile, only one Log College grad we know of did anything except enter the ministry. (Philadelphian John Redman, who was the medical mentor of Benjamin Rush 1760, chief surgeon of Washington’s Army.) So the personal and philosophical ties from Tennent Sr. and his Log College may only have sparked the Big Bang, but it certainly arose from no mere quantum tunneling..

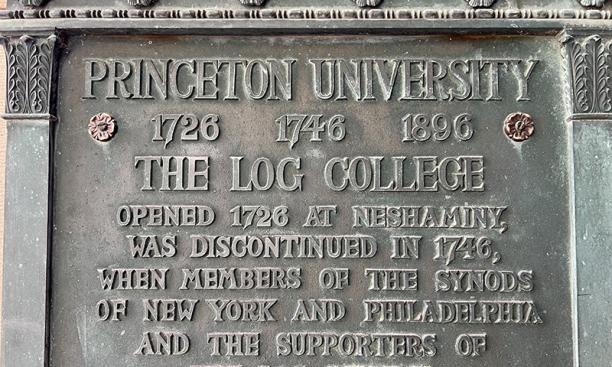

Looking at the same puzzle in 1896 following the new University’s sesquicentennial relaunching, Princeton commemorated the debt. The resulting plaque remains the sole place on campus where the Log College, now a proud symbol of Colonial America rather than a snide remark, is noted, but the placement is telling: on the doorpost outside the entrance to Nassau Hall, now a national historic site. In a tribute to narrative diplomacy, it reads in full:

Princeton University

1726 1746 1896

The Log College

Opened 1726 at Neshaminy,

was discontinued in 1746,

when members of the Synods

of New York and Philadelphia

and supporters of

the Log College

united in the organization of

The College of New Jersey

at Elizabeth Town.

First charter granted Oct. 22, 1746

by King George the Second

through John Hamilton,

acting Governor in Chief

of the Province of New Jersey.

Second charter granted Sept. 13, 1748

by King George the Second

through Jonathan Belcher, M.A.

Governor in Chief

of the Province of New Jersey.

On Oct. 22, 1896, the name of

the College of New Jersey

was changed to

Princeton University

----------------

Dei Sub Numine Viget