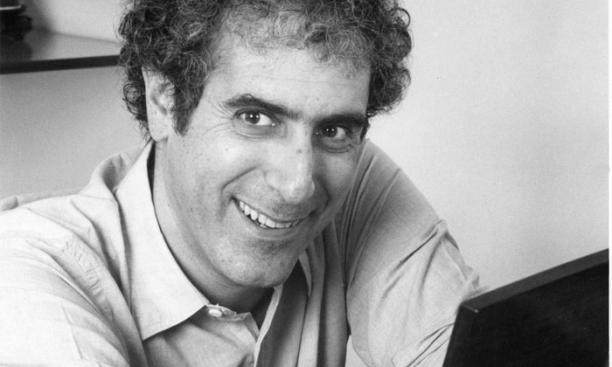

He began his songwriting career in the Triangle Club with a “How to Succeed”-like send-up of big business at an advertising agency called S.E.L. & L., and he ended it as one of the most successful creative forces in the history of noncommercial television. In between, Jeffrey Arnold Moss ’63, the founding head writer of Sesame Street, racked up 14 Emmys and an Academy Award nomination, and helped teach hundreds of millions of children worldwide a good bit about what it means to be human.

It was Moss who made one of Jim Henson’s scruffy blue Muppets, then known only as Boggle Eyes, into that indelible chocolate-chip-aholic, Cookie Monster, and who wrote Oscar the Grouch’s grumpy anthem: “Oh, I love trash! Anything dirty or dingy or dusty. Anything ragged or rotten or rusty. Yes, I love trash.” It was he whose humble hymn to a bathtub toy, “Rubber Duckie,” became a million-selling single that wound up in the top 20 on the Billboard pop music charts in 1970–71. If Henson gave the Muppets their form, and Frank Oz provided so many of their voices, Moss helped give them their souls.

So it should come as no surprise that a panel dominated by parents of post-baby boomers saw Moss, who died of colon cancer at 56 in 1998, as a must for its list of Princeton immortals. Precisely because he wrote the words that cultural touchstones still speak and sing, the panel saw his work as more lasting — and thus more influential — than even that of a better-known and perhaps even more-beloved icon, Jimmy Stewart ’32, who narrowly missed making the final list.

By the end of the panel’s discussion, it also was clear that, fond as the group was of Moss, he was something of a proxy for a whole pond of Princetonians in the performing arts — from Stewart, the director Joshua Logan ’31, and actor José Ferrer ’33 to Moss’ contemporary on the staff of Captain Kangaroo, Clark Gesner ’60, whose You’re a Good Man, Charlie Brown ranks as the most-often-produced musical comedy in the world, owing to its countless high school and amateur incarnations. (In his new biography of Charles Schulz, Schulz and Peanuts, David Michaelis ’79 estimates that there have been more than 40,000 productions of the show over the years.)

“I would say Jeff would be, in his quiet, enthusiastic way, so thrilled,” Moss’ widow Annie Boylan tells me by phone from her home in the Hudson Valley of upstate New York. “Obviously, Princeton was huge in Jeff’s life. He loved his experience there. He came out of New York City, where he was No. 1 in his class” at the Browning School, “and then, he said, he finally got into a school where he wasn’t No. 1 anymore. He had to cope with that the first two years, and then he found the Triangle Club.”

Moss came by his creativity naturally. His father, Arnold Moss, was a respected Shakespearean actor, longtime college drama teacher, and prominent creator of New York Times crossword puzzles, who played the Ziegfieldian impresario in the original Broadway production of Stephen Sondheim’s Follies. Moss wrote his Princeton thesis on Shakespeare, and went on to write numerous books of poetry and stories in verse, including Bob and Jack: A Boy and His Yak.

“What was most interesting about Jeff is that he wrote ‘Rubber Duckie’ and all those wonderful songs before he was married and had a child,” his longtime literary agent, Esther Newberg, recalls. “That he had the sensibility to write all those romantic and lovely children’s songs. He was as precise in writing those songs as he was in reading his contracts and royalty statements. There are lots of writers who are hugely famous who don’t know anything about the details. He always took the time. Some of his songs are deceptively simple. But he worked so hard.”

Upon graduation, Moss was offered two jobs at CBS: as a production assistant for the CBS News, or for Captain Kangaroo. He chose the latter, he once said, because, “I’ve seen the news.” In 1969, along with other Kangaroo alumni, Moss wound up helping to start Sesame Street, with the intention of appealing to both adults and children. Over the years, a parade of famous figures from Johnny Cash to Julie Andrews performed Moss’ material, including Ralph Nader ’55, who insisted on changing the lyrics of “The People in Your Neighborhood” to replace a colloquial “that” with a grammatical “whom.”

“Jeff was sort of a genius, a creative genius,” says Joan Ganz Cooney, the creator of the Children’s Television Workshop and founding mother of Sesame Street. “Jeff was a sort of child himself, and I don’t mean he had a way with children. I mean he, himself, was a kind of a child. He could be very difficult, very prickly. He could write anything, he could imagine anything. He himself was a very sober guy, not funny at all ... I loved him.”

Moss’ widow says, “I think there’s a small chance that maybe he didn’t completely get the credit” he deserved in the public mind, “like the speechwriter doesn’t get the credit. What would all those puppets be without Jeff?” She adds:

“A lot of people remember Henson, and Henson, of course, was brilliant. But Jeff put the words and the personality in the puppets. He formed most of the personalities of these people.”

Moss began writing children’s poetry when the actress Marlo Thomas asked him to contribute to a book she was putting together, Free to Be a Family. He wrote a poem called “The Entertainer” about a little girl who feels imposed on when her parents ask her to perform at parties. Comparatively late in life, Moss married and fathered a son of his own, Alexander. “He was diagnosed when Alex was 3, and he told me he was going to get this kid to the age of reason,” Boylan recalls. “He had 14 operations. Three months after Alex turned 7, Jeff died.”

Cooney still remembers how Moss, in a wheelchair with a portable oxygen tank, came to the Children’s Television Workshop offices to say goodbye to his fellow writers and old friends. “People got to stand up and say how they felt about him, and he did the same,” she says. “It was the most generous thing I have ever seen a dying person do.”

Boylan tells me that, not long before his death, Moss attended a memorial service in the Princeton Chapel, at which all the names of Triangle members who had died since the club’s founding were read solemnly. Alone at a piano, he performed a composition he had written for the occasion called “The Song Goes On.”

Todd S. Purdum ’82, former White House correspondent for is national editor at magazine.