When the men of Princeton’s Class of 1885 prepared to gather for their 25th reunion, they decided to publish a book reporting the latest doings of classmates “in anticipation of the reunion in June, 1910.” The 116 pages of the resulting hardcover volume did that and more: They not only provide brief sketches of the 165 or so 1885ers who contributed their biographies, but also open a window into belle époque life. Meet Chester Allen Arthur of Colorado Springs, “the Colorado representative on the committee for the Taft inauguration ball. He drives a four-in-hand, and otherwise leads the life of a gentleman of leisure.” Less fortunate since graduation, perhaps, was Dr. William E. Woodend. He was listed with “Address Unknown” and identified as “a broker at one time. The New York Sun of May 1, 1904, has a couple of columns on the smash-up of his firm.”

The slender Class of 1885 volume is among the Princeton 25th-reunion books assembled in a reference room in the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library. The 25th-reunion books — which date back at least to one published by the Class of 1853 in 1878 — are the keystone volumes in the Mudd Library collection of 25 shelves of books published by Princeton’s classes at their major (and sometimes minor) reunions. Just as 1885’s book preserves a sepia-tinged snapshot of the turn of the century, the collection bears witness to the marriages, children, job changes, aspirations, vacations, midlife crises, and personal victories of generations of alumni. These details are gathered into narrative essays — the life stories of people who choose to tell us about who they are and how they got there. The narratives they construct — what they put in, what they leave out — can tell us much about the changing character of Princeton alumni and the times they lived in.

When the Class of 1897 published its first book, a directory of classmates’ addresses, just a year after graduation, it added a special tribute to the class’s “war heroes” serving in the Spanish-American War, which had broken out in 1898. It was the first of many reunion books that periodically reflected the impact of a foreign war. At the 25th reunion of the Class of 1969, 80 percent reported that they held advanced degrees — a lingering result of the Vietnam-era draft deferment given to graduate students in those days.

The books reveal the character of their times in other ways. Early Princeton reunion books listed classmates not only alphabetically but also by their professions. In its first-reunion book, for instance, the Class of 1899 grouped classmates under the headings “studying,” “business,” “draughting and engineering,” “journalism,” and “practicing law.” (Future physicians were listed as still “studying.”)

More recent Princeton alumni cannot be grouped so easily. John Oakes ’83, who drafted and analyzed the class survey for the most recent 25th-reunion book, was struck by his classmates’ diversity. “There are many lawyers and financial people in traditional careers, but they are very open to life and ‘liberal’ in the general sense,” he says. “They have not become narrower, as you might expect. They have broadened in their interests and attitudes.” Nor are the members of ’83 single-mindedly committed to their careers. Having already dealt with the work-family balance, these alumni “say it’s not all about work for them; it’s about family,” according to Juli Greenwald ’83, who edited her class’s 25th-reunion book (which was not yet available when this article went to press). “Work is nice, but it’s not the be-all and end-all.”

Other recent 25th-reunion classes appear to have shared in that experience. A visitor from Mars examining the Class of 1982’s 25th-reunion book — a lively, four-color volume that includes 350 individual profiles, a class survey with computer graphics, and several hundred photographs — might conclude that Princeton was educating a generation of adventurers. The men and women of ’82 are seen skiing, boating, helicoptering, and fishing in locations that range from Boston to Baghdad to the South Pole. They are accompanied by spouses, same-sex partners, children, pets, and at least one frog. Pictures submitted by alumni from classes as recently as the early 1970s were dominated by formal, publicity-department head shots, but I could find only two photos of ’82ers in a professional setting, and in one of them the alumnus is juggling.

Not that ’82 is lacking in professional accomplishment. Theirs is an elite chosen for success, and the book is peppered with now-prominent names: the actor David Duchovny, Democratic Party activist Bruce Reed, Hollywood studio president Theodore Gagliano, and AOL executive Lynda Clarizio. There is a large group of published authors and journalists, including Joel Achenbach, Lisa Belkin Gelb, Christopher Chambers, Bart Gellman, Michael Lewis, Virginia Postrel, and Todd Purdum — all of them from one of the last classes of undergraduates that did not use personal computers at Princeton. Asked about this literary flowering, the book’s editor, Elizabeth “Wiz” Lippincott ’82, observes, “Many of us didn’t feel the need to go to graduate school to succeed. [It was a time] when magazines and newspapers were strong, and the best education was on the job, not in a classroom.”

One virtue of reunion books is that they prompt a kind of periodic self-assessment before a comparison group of your peers. Is your career meeting your expectations? What about your family priorities? What are your goals? At their 25th, the men and women of ’82 contributed remarkably candid essays, perhaps because they felt safe addressing a trusted group of friends. They know that they are extraordinarily privileged; almost all express gratitude for the blessings in their lives. Some essays are humorous and self-deprecating. More serious ones comprise a mosaic of themes that emerge again and again: the joys and difficulties of parenting, the passing of one’s own parents, the slightly anxious jokes about losing car keys and forgetting names. The motif of the so-called midlife crisis is heard again and again from this group of ambitious 47-year-olds: “After 20 years in software sales, I finally committed to follow a calling I feel I have always had to become a teacher and football coach.” ... “Twenty-five years on, I’ve changed — more rhythm, less blues” ... “Maybe I’ve had a midlife crisis, and maybe I’ve just come to trust what I believe.”

As Greenwald discovered in editing the ’83 book, Lippincott reports that a dominant theme in the 1982 essays was “the effort made and candidness to write about finding a work-life balance. Normally you would hear about this from women, since we feel the stress of being child-bearers as well as putting our Princeton educations to work. But I thought it interesting that in almost every essay the guys wrote, they talked about trying to be with their kids and spouses as much as about their career ladder.”

In a typical entry, one woman writes about traveling the world with her company until “we just couldn’t pull off a two-career family any more. Now I’m happily home with two teenagers and a Labrador ... .” Another ’82er left his international banking job with Citibank after he and his wife “decided that the time had come to settle down and give our children, now in middle and high school, the opportunity to finish high school with their friends.” He now works at a community bank in Florida where “I am currently experiencing the enormous satisfaction, as well as the risks, opportunities, and rewards, of being a small-business owner and operator.” Lippincott herself worked as a reporter and magazine editor in Los Angeles before, as she writes in her essay, “I left the journalists’ entitled world of glamour, celebrity, and access, after 15 years, to raise my three children.”

Some of ’82’s essays are somber. “I will be a four-and-a-half-year survivor of pancreatic cancer” ... “In August of 2005, I was diagnosed with colon cancer. The cancer had spread to the liver in eight to 10 places, and the prognosis was pretty bad” ... “There have been dark years on the way to the present moment.” But as is common for high-achievers, many of the Princetonians find a positive and even redemptive narrative to explain the most difficult experiences life presents. A cancer patient reports, “This experience has made me appreciate the simple things like family and friends and even the kindness of strangers and acquaintances.” One of the book’s most moving essays was contributed by Gina Malin, the widow of Bob Malin ’82, who died of a heart attack during the couple’s 20th-anniversary vacation a year before the reunion. Gina lists 14 things her husband had done in the two weeks before he died, almost all of them involving service to others (e.g., “Helped his oldest daughter with a science project ... Mentored a young friend”). “We miss and love him so,” she concludes.If 25th-reunion books represent a kind

If 25th-reunion books represent a kind of taking-stock at midstream, the classes preparing 50th-reunion books are closer to the far bank. This year, the Class of 1958 published its 50th-year book well in advance of its June reunion. It is a substantial volume: 465 pages, 9" x 11" trim size, with 441 individual profiles set in a generous typeface that will not strain 72-year-old eyes.

Where the men and women of ’82 and ’83 are diverse and centrifugal in their interests, the men of ’58 are comparatively homogenous and centripetal. By the time of the 50th reunion, many of the issues ranked high among the priorities (and anxieties) of the 25th-reunion classes have been resolved long ago. Careers have been settled; children are grown and (mostly) out of the house. The ’58ers are mellower; they have moved on to the stage of life Erik Erikson calls “generativity” — when, after one’s own identity and long-term bonds of intimacy with family and friends are established, an adult is ready to lead and help the next generation. Remak Ramsay ’58, a longtime Broadway actor, writes in his essay, “We should spend less time worrying about the next quarterly dividend and more time worrying about the next generation.”

The photos submitted have a relaxed elegance, as if from the pages of Orvis or Land’s End catalogues. There are fewer photos submitted from mountaintops, though one ’58er is depicted gripping his pitons. Instead, the pictures are quieter, often just an alumnus and his wife, sometimes with grandchildren and pets. (I counted seven dogs, two hawks, one horse, and two dead fish.) They are joiners. One man writes, “We belong to a number of social clubs; in New York the Harmonie Club, Doubles, and Sunningdale Country Club; in the Hamptons the East Hampton Golf Club, East Hampton Indoor Tennis, Maidstone Gun Club, and the Peconic River Sporting Club.”

If the men of ’58 wrestled with finding the family-career balance that preoccupied the Class of 1982, they do not talk about it much here. Some of 1958’s most prominent members present an understated synopsis of their recent years. Former U.S. Senator Jack Danforth ’58, for example, writes in a just-the-facts mode, “I’ve had some interesting assignments since leaving the Senate, including acting as special counsel to investigate the deaths caused by the federal raid on the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas; and serving as President Bush’s special envoy for peace in Sudan.”

The accumulation of years lived by the 50th reunion can bring heartbreaks along with satisfaction. His marriage ended, one classmate “took it hard, did therapy, learned to meditate.” Another one understands “that my alcoholism, which I had failed to address, was responsible for the end of this marriage and the end of a very promising corporate career.” Some report with sadness the deaths of their children: “Fiona had a severe breakdown, was hospitalized, and later died. That death was a terrible blow” ... “Dedee and I suffered our worst tragedy when our youngest son, Tyler, was killed in an automobile accident at the age of 23” ... “After Terry’s sudden death in March 2007, while playing hockey, he received many wonderful tributes and memorials.”

Many of the 81 obituaries printed in a special section were written by widows, family members, colleagues, or classmates. Unmitigated by professionals, they are especially affecting: “Sandy died of cancer on Nov. 27, 2004, near our home in Yardley, Pennsylvania. I was with him. ...”

There is a self-effacing resoluteness among the members of this so-called silent generation that shines through. One ’58er writes, “I’ve never gone back to Princeton and am hardly a rah-rah alum. But Princeton is with me always — when I least expect it, when I find myself able to discuss sprung rhythm with our local poets, or when I have to think my way out of some awful mess. I love telling people I went to Princeton: Their eyebrows go up and so does my IQ for a moment, back to where it was when I was bright enough to gain entry to ‘the best old place of all,’ where I learned to love books, work hard, walk fast, and never, never, never give up.” In a postscript, this alumnus adds that he recently returned to working on land-preservation issues in his community “because I don’t want to die drooling in a wheelchair. I want to be shot by a rabid developer.”These recent volumes are part of a

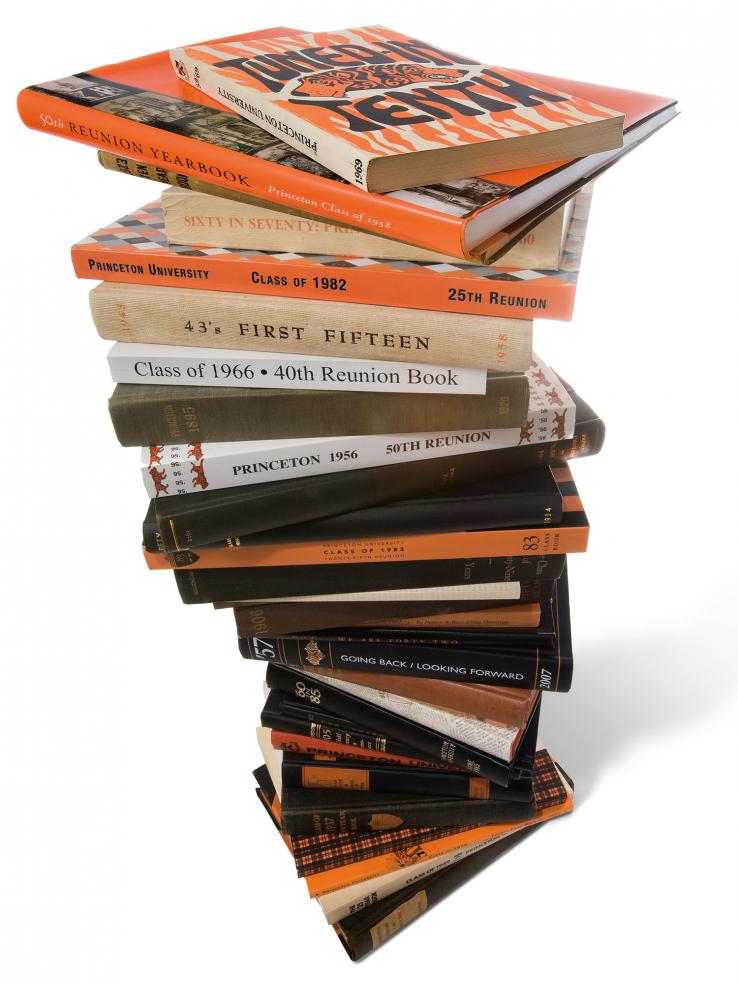

These recent volumes are part of a century-and-a-half-long evolution of reunion books that continues today. With the introduction of offset and desktop-publishing technologies, the books have grown in both ambition and girth. The tidy, Nassau Herald-sized, faux-leather format used by many classes of the 1950s and 1960s for their 25th-reunion books has given way to splashy, four-color softcovers. The 50th-reunion books have changed and expanded even more dramatically, hitting a high mark with a Brobdingnagian effort from the Class of 1952, which in 2002 published a 758-page Book of Our History, a separate volume of essays written by classmates, and a CD of Princeton songs.

A number of recent reunion books have been produced by Hugh Wachter, an enterprising member of the Class of 1968. A former commercial publisher, Wachter got into the reunion-book business when he was asked by his class to help out with a book for its 25th. After other classes sought his assistance, Wachter started his own company, Reunion Press in suburban Washington, D.C. In the years since, in collaboration with Web site developer John Bruestle ’78

of Reunion Technologies, Wachter has edited and published more than 100 reunion books for alumni of a number of schools and universities. But with the advent of coeducation and the resulting expansion of Princeton’s graduating classes, it has become increasingly difficult to produce the volumes. Ultimately — perhaps within 20 years, he suggests — the printed volumes may be replaced by Web sites. “The younger classes are not even thinking about books,” Wachter says.

The move away from hard-copy reunion books is not welcome news for social historians. Consider the graduates of 1968 — a class, more than any other, shaped by the turmoil of the 1960s. The first class composed largely of baby boomers, it entered Princeton the year after the assassination of President Kennedy and left with the assassinations of Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. In the years since, they have had to reconcile their original self-narratives with the lives they actually led. The class’s 25th-reunion book is an extraordinarily rich document that in 1993 still crackled with the frankness and tension of those earlier times. Listen to the voices of its members:

• “The late ’70s and early ’80s were an increasingly miserable and self-destructive time in my first marriage and family life. ... I’ve learned much from the pain, the sorrow, and the triumphs.”

• “Early in the course of practicing law, I had become addicted to the intoxicating excitement of transactions. ...

As with any addiction, I needed ever-increasing ‘deals.’”

• “One of my summer reading books, Tantra: The Supreme Understanding, by Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, affected me so profoundly that I traveled to Poona, India, in 1979 to meet Osho Rajneesh (as his disciples were later to call him).”

• “My first marriage dissolved shortly after my return from Germany in 1971. I had had virtually no practical experience in close relationships before I met and married ... (a condition which Princeton’s all-male character during the ’60s did nothing to ameliorate) ... ”

• “I left Princeton in 1968 anticipating going to jail because of refusal to serve in the Vietnam War. I had applied for conscientious-objector status after much deliberation on my willingness to accept imprisonment and abandon my hopes for how my life would turn out.”

• “With the Tet offensive and the end of draft deferment, we were all scattered like birdshot in June ’68. ... I joined the Navy; with misgivings, but ready to give it the benefit of a doubt and be convinced by the reality. Strangely enough, I never got hold of much of the reality.”

This spring the Class of 1968 returned for its 40th under its reunion slogan, “It’s About Time.” Indeed it is. How did its members turn out? What are their reflections now about the ’60s, Vietnam, coeducation, student unrest? Alas, we do not know. The Class of ’68 did not publish a book for its 40th reunion this year. To read classmates’ stories, we must wait until they are called to write about it at their 50th.

It will be a useful exercise. In his influential book, The Stories We Live By, the Northwestern University psychologist Dan P. McAdams argues that our life stories not only describe who we are, but can shape our futures. “We each seek to provide our scattered and often confusing experiences with a sense of coherence by arranging the episodes of our lives into stories,” he writes. “This is not the stuff of delusion or self-deception. We are not telling ourselves lies. Rather, through our personal myths, each of us discovers what is true and what is meaningful in life.”

Landon Y. Jones ’66 is a former editor of PAW and People magazine. His 1980 book, Great Expectations: America and the Baby-Boom Generation, was reissued in softcover this year by Amazon’s Book Surge imprint.