Soon after coming to Princeton, in 1973, to teach photography, Emmet Gowin began to worry that he’d made a big mistake.

He’d taught for four years at the Dayton Art Institute and another two at Bucks County (Pa.) Community College, and he was well on his way to building the reputation he has today, as one of the great photographers of our time, an artist of consummate technical skill and deep poetic feeling. But what exactly could he offer these young men and women, who seemed so bright and sophisticated?

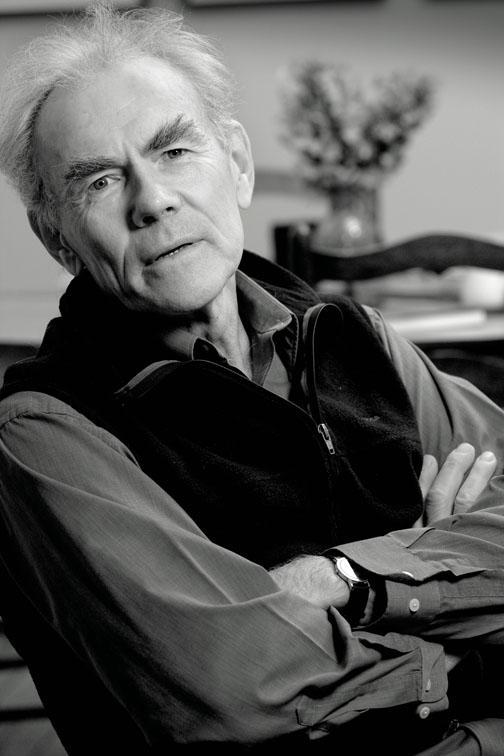

Thirty-six years later, it seems absurd that such thoughts ever crossed his mind. It’s hard to imagine anyone better suited to teaching bright undergraduates — virtually none of whom comes to Princeton planning to become a photographer — than Gowin, who approaches the world with curiosity and wonder and a deep humility before the great mysteries of life. “Emmet taught us how to ask questions, how to find meaning in the world around us,” says Elise Wright ’83, who works as a photographer and graphic designer in Hopewell, N.J. “Photography, with Emmet, became the study of everything.”

Gowin was the first “art” photographer to teach at Princeton. He plans to retire at the end of this term, and is being honored with a show at the University Art Museum that includes not only 25 of his own pictures but also one each from 20 of his students, going back to the mid-1970s. Some of those students have become celebrated photographers in their own right, including one, Fazal Sheikh ’87, who has won a MacArthur “genius” grant. Others have gone on to curate some of the top photo collections in the world: Malcolm Daniel *91 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City; Peter Barberie *07 at the Philadelphia Museum of Art; and Ellen Handy *94 at the Ransom Center in Austin, Texas.

“The contribution Emmet has made is just indescribable,” says Peter Bunnell, who came to Princeton in 1972 to create the country’s first Ph.D. program in the history of photography and recruited Gowin a year later. “He gives everything of himself. ... The idea that you had trouble figuring out how to mix the developer could be solved in two seconds. But what you really had to figure out was: What am I making a picture of and why? What does it mean? And Emmet is just so good at articulating that.”

Indeed, a conversation with Gowin in the airy kitchen of his home in Newtown, Pa., is like setting off on a long ramble in the company of wise men and women from different disciplines and times — with Heisenberg, say, and William Blake and Wittgenstein. You don’t know exactly where you’re going, but you know it’s going to be fascinating getting there.

Gowin was born in Danville, Va., which sits on the state’s border with North Carolina. Emmet Gowin Sr. was a Methodist minister, a doctor of divinity serving a community where few finished high school. While sincere in his striving for goodness, Emmet Sr. had a narrow sense of right and wrong. “My father frightened me with his theology,” Gowin told one interviewer. “He was so tender but carried also in him this thou-shalt-not,” Gowin recalls today. His mother was a Quaker, and young Emmet found comfort in her gentler approach to the world. Still, there’s no doubt that he has his father to thank for his love of language and stories. “I grew up listening to his sermons,” he says.

When Gowin was 2, the family moved to Chincoteague Island, where he wandered the marshes sketching birds and plants and marveling at the changes he saw in nature. In his early teens, he saw an Ansel Adams photo of a burned stump sprouting new shoots, which the minister’s son immediately knew was an image of resurrection. “I had never thought of a photograph as anything but a representation of what it was,” he muses. “I was defenseless [before it]. I thought it was Christ. This was the body dead and resurrected. But it had been transformed: It was not the same matter it left the world in. That was closer to my own theology, too.”

He was saved, in a way, the night he went to a dance and met Edith Morris, who became his wife in 1964 and remains among his most important photographic subjects. Theirs is a collaboration of equals. Even now, when he talks about their marriage, Gowin’s voice trembles with emotion: “If you are married, if you think you love somebody, that’s the sacred moment in your life,” he says. “Treat it as if it’s sacred.”

What Edith remembers most about the night they met is how exotic he looked: “He was all in black,” she recalls. “Elvis dressed in black, but nobody else did. It stood out that he was an individual, even then. He collected stamps and coins and had gotten his Eagle Scout badge. He listened to jazz. I never saw anybody like this! Where did this guy come from?”

Some of their dates took them driving down into North Carolina — “just holding hands and kissing every so often, the way you do,” says Gowin — where they visited a black church out in the country, and he shyly asked for permission to take some pictures. The minister appealed to the congregation. “Amen!” the people roared. These photos became one of his earliest books, a beautiful handmade volume of which Gowin made six copies.

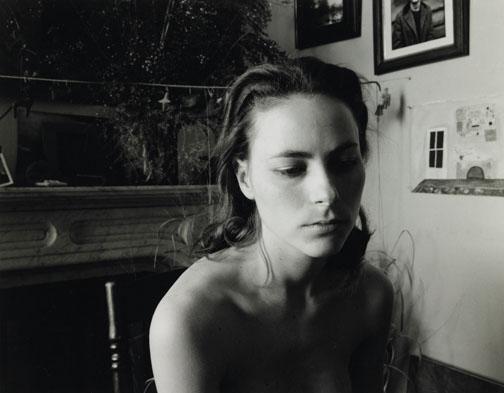

Gowin was embraced by Edith’s sprawling family, which could not have been more different from his. They were millworkers with little formal education, but a bottomless supply of kindness and acceptance. He began to take photographs of Edith and the family as they worked and played on the farm. Viewed together, they are a detailed record of life on a particular farm, at a particular time. But they also seem timeless, luminous, as if a window has been opened onto what Gowin, channeling mythologist Joseph Campbell, calls “the radiance of the invisible that comes through the visible.” In one, two children wrestle on the grass; in another, they play with a spouting hose. Many are of Edith, who, in some photographs, is naked.

In his introduction to his 1976 book, Emmet Gowin: Photographs, Gowin explained the moral bargain he felt he was striking when taking these photos: “I admired their simplicity and generosity, and thought of the pictures I made as agreements. ... My attention was a natural duty which could honor that love.” Gowin has hundreds of photographs of Edith, making a thorough record of their 45 years of marriage. They are now collaborators on a true labor of love: “We always thought that somewhere near the end of our lives there would be a book of pictures of Edith,” he says. “We always felt like we should take that as far and get as old as we can in the making of those pictures because the beauty of youth is just too much. But beauty being older is another thing.”

Though Gowin started college in Richmond as a business major — “a camouflage trick for my parents” — he soon switched to photography. He went off to the Rhode Island School of Design in 1965 to do graduate work with Harry Callahan, one of American photography’s greatest innovators. Within a week of his starting school, Gowin got a letter from his draft board. “I wasn’t going to register for the draft,” he says. “I didn’t believe in killing people, and I didn’t understand what it was all about.” He drove back home to explain this. His draft board, it turned out, was made up entirely of women, and amazingly understanding women at that. They urged him to apply for status as a conscientious objector, which he did.

That same weekend, he took a picture that caught him by surprise and taught him a valuable lesson: to resist what he calls “the control me,” the part of him that had rigid plans for the future. He had brought a camera but had no film. He borrowed some film holders from Callahan, who warned him that he wasn’t even sure they contained film. Back at the farm, Edith’s niece, Nancy, begged Gowin to take a picture of her. He did, and sensing he might have captured something special, he rushed to a friend’s darkroom to develop the film he hoped was inside. In the gorgeous picture he’d made, Nancy lies in the grass surrounded by a halo of her dolls. Looking at that photo, he says, “I felt like the old me had died and something else emerged. I had gone home for an entirely different reason, not of my own choosing. And here it was, like a gift: There was film in the camera. There was a child saying, ‘Take my picture.’ The most important things come to us in this way, as a kind of unearned grace.”

“The point was the intimacy” of the family photos, says Joel Smith *00, who is curating the Princeton exhibition. “What was important to him was to record this relationship between himself and this world he was in. That was as interesting as anything he could go out searching the world for. The connection was the thing that made it worthwhile.”

In 1971 Gowin got the sort of break any young artist hopes for: a two-man show, with Robert Adams, another young photographer, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The first reviews were terrible. “They couldn’t see beyond the snapshot [quality] what he was doing,” says Smith. “It took some time for the emotional power of the works to come through. That was something he needed to teach the world of photography.”

The curator of the MOMA show was Bunnell, who moved to Princeton the following year. Back then, photography was under the auspices of the architecture school and was offered as either a kind of practical “art experience” for architects or a therapeutic palate cleanser for students needing a break from their “serious” work. At first, Gowin’s was a part-time position. With no one quite sure what to make of it, he was free to shape the curriculum as he pleased.

Gowin’s classes tended to begin with a question about some technical problem that he himself was wrestling with — for example, the proper lens length or the nuances of light. But they’d quickly turn to the richer questions that have always made Gowin’s teaching so effective: “What is home to you?” he’d prod gently. “What is the difference between home and every place else? Why do you love some things and not love others?”

Gowin was also reluctant to come right out and tell students what he thought of their work. Like the late photographer Frederick Sommer, who was his friend and mentor for 30 years and encouraged him to read widely, Gowin can sound cryptic and mysterious, as if inviting further meditation on a topic. “One great gift was his refusal to give pat answers,” says Sheikh, who describes himself as an “artist-activist” working with displaced people around the world, most recently in Somalia. “Art is about the fact that no one can give you a clear and concrete answer, which is frustrating when you’re starting out.”

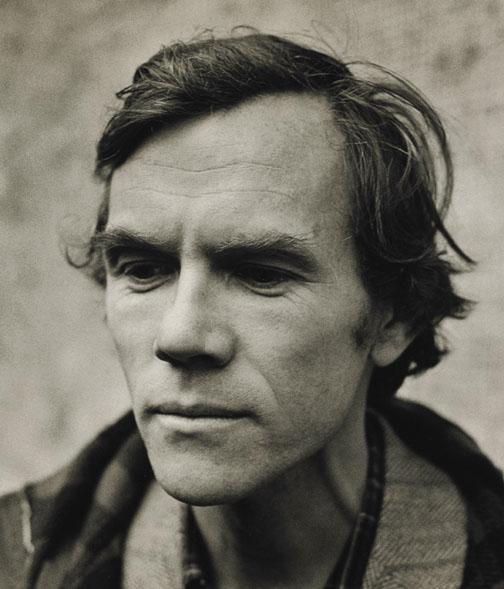

As a student, Sheikh had been making self-consciously arty work that explored his African heritage. On a trip to his father’s family home in Kenya, he took some portraits of local people. He didn’t think much about them until he showed them to Gowin, who was struck by one particular image of a local man. He urged Sheikh not to overlook this simply because it seemed easy to make or was overly familiar. This was the same lesson Gowin himself had learned about his pictures of Edith and her family: What was important was the emotional connection.

He taught the students how to make a mask, a kind of three-dimensional overlay that exaggerates the light and shadow, and how to use selenium, a toner that adds a red or purple tint to a print. One of his favorite assignments was to ask students to experiment with old processes, like callotypes from the 1840s and gum bichromate prints from the late 19th century. When one student, Art Carpenter ’83, built a 4 x 5 camera out of wood, no one was more delighted than Gowin. Starting in 1987 Gowin began to assemble a year-end portfolio to which each student contributed one photo. Gowin, too, would include one of his, one more reminder that he was just another humble student of the art.

Meanwhile, the teacher’s own work had continued to evolve. On a trip home to Danville the year he came to Princeton, he noticed that children had built a tree house, and out of curiosity he climbed up to take a look. “Just getting up to a high place changed and liberated your vision,” he says. It dawned on him that the landscape and its occupants were bound together inextricably. “It was an awareness that this place had not always looked this way,” says Gowin, but had been shaped by the people who lived there.

The photo he made from the treehouse, View of Rennie Booher’s House, Danville, Virginia, prompted Gowin to broaden his focus to include landscape — the world that people live in. After a disappointing trip to Peru in 1974, on a Guggenheim Fellowship, which had yielded little other than the sense that he didn’t really understand the place, he was visiting friends in Italy and began to take “working landscapes” — pictures of local people picking olives in Siena and, later, shearing sheep in Yorkshire. These were healthy landscapes, affirmations of man’s legitimate place in nature if he is respectful and careful. In 1980, a few weeks before he was to begin taking pictures of Washington State landscapes commissioned by a Seattle arts group, Mount St. Helens exploded. After six weeks he had about 500 shots of landscapes, but even the best ones struck Gowin as generic photos of the American West. He found a pilot willing to take him up over the crater. In an hour and a half he had taken 18 pictures that all were better than the earlier shots. The world looked different from a plane.

On one trip to the volcano, David Maisel ’84 went along as Gowin’s assistant. He recalls how they hiked into a forbidden zone lugging an 8 x 10 camera, tripod, and other equipment, and became lost (Gowin, a former Eagle Scout, found the way out). “This willingness to put yourself in physical risk, but carefully not carelessly, and to have repeated encounters with subject matter that pulled you in — that was important,” says Maisel.

Gowin was awed by the forces he saw at work at Mount St. Helens. He began to wonder at human attempts to change or harness nature, and the awful results. Since then he has taken aerial pictures of golf-course construction in Japan, strip mining in the Czech Republic, and toxic-waste aeration ponds in Arkansas. He’s flown over Hanford, Wash., the source of plutonium and a place where no one can live for the foreseeable future. Thanks to Gowin’s meticulous craftsmanship, many of these scenes are not immediately recognizable. They look like stunning abstract paintings.

After 10 years of petitioning the government, he finally was given permission in 1997 to photograph nuclear test sites in Nevada. At first this was exhilarating. “But by the third time, I was just so heartsick,” he says. “I didn’t want to think about tearing the world apart anymore.”

That was Dec. 23, 1997. Gowin flew home for Christmas and then was off to Ecuador, where through a mutual friend he’d been invited to spend time with an entomologist whose family collected butterflies and moths. Crawling around on the jungle floor he was terrified of snakes, but at the same time astonished by what he saw, by the beauty and abundance of life, unlike anything he’d ever seen before. It was the perfect antidote to the blasted world he’d just come from. He felt an irresistible pull similar to the one he’d experienced when he’d met Edith’s family, and began returning to the jungle on school breaks, attaching himself to small scientific expeditions. He is retiring now partly, he says, because he feels an urgency to finish this project. “You don’t know how much time is allotted to you, and the best time to go is right in the middle of the school year.”

And so it is back to the jungle and to those striking moths, which, he notes, show best “in the dark of the moon. They come to the light, which is pretty wonderful.” He hopes to make a book of 100 pages; by midsummer, he had 27. Gowin arranges 25 pictures on each page, in rows of five.

Merrell Noden ’78 is a frequent PAW contributor.