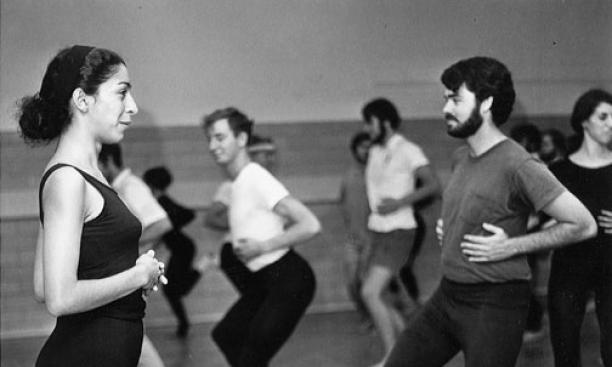

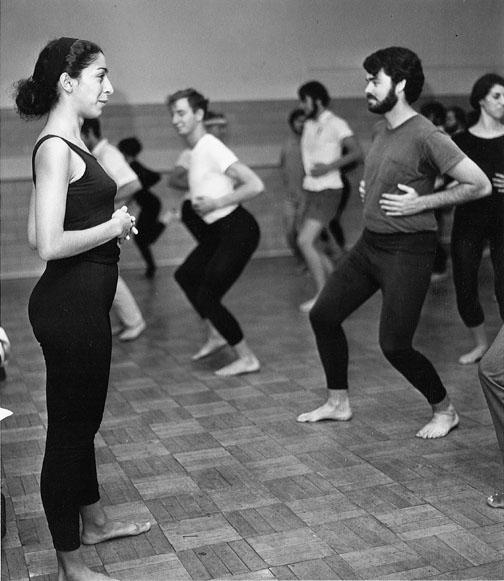

In a similar way, Cohen came to Princeton in 1969 with a vision of bringing instruction to each class not only in dance movement, but in choreography and critical writing as well — improvising with the resources available until, 40 years later, the seed has blossomed. Today a professor of dance, Cohen will retire in June.

Cohen’s multidisciplinary approach transformed two generations of students, ranging from novices who had no idea what a plié was to those with ballet barre training.

“Ze’eva changed lives in the studio,” says Jill Sigman ’89 *98, a choreographer who has performed with Cohen. “For some it was through simply sharing the joy of moving and the value of a physical existence in the world. For some it was about making connections between dance and other fields of study. For some, like myself, it was about revolutionizing their aesthetics.”

In recognition of Cohen’s achievements as a dancer, choreographer, teacher, and head of dance for nearly 40 years, the Lewis Center for the Arts is sponsoring a tribute April 3 at 6 p.m. in McCarter Theatre Center’s Berlind Theatre. Utah’s Repertory Dance Theatre will perform two Cohen-choreographed works: “Rainwood,” a signature piece, and “Ariadne.” Seven alumni will dance “Wig Wise,” a Cohen piece set to Duke Ellington’s music. Also on the program is a decade-by-decade photo retrospective of dance at Princeton.

Cohen’s first noncredit class (it became a for-credit course in 1971) was in modern dance — she says it provided an accessible starting point for a wide range of students.

Since then, Princeton’s dance program has grown to nearly a dozen courses in movement, choreography, dance history, and performance, taught by 13 faculty members and guest artists. With the division of the Program in Theater and Dance into two separate entities last year, and Susan Marshall’s arrival in September as the first director of dance, Cohen’s foundational work has evolved to a new level.

An established performer before teaching at Princeton, Israeli-born Cohen came to the United States in 1963, trained at Juilliard, and danced with the Anna Sokolow Dance Company, as well as with other troupes.

Cohen then branched out with what was, at the time, a trailblazing concept — a one-woman show of works by different choreographers. For a dozen years she toured internationally before starting her own dance company.

She taught part time at Princeton when she was not on the road. Fifty of the 60 students who enrolled in her first course were men, and the first performance, “To Dance Is To Live,” was an outdoor Earth Day celebration on Poe Field. In 1974 the Program in Theater and Dance was established under the umbrella of the Humanities Council, which allowed undergraduates to work for a certificate (the program now is part of the Lewis Center). The introductory course affectionately became known as “Dance for Klutzes.”

In the 1990s Cohen began teaching full time, and Princeton’s dance program adapted to the changing needs of undergraduates. The gender balance shifted, and students with years of training behind them began to clamor for more classes devoted to technique. This spring, for the first time, Princeton is offering a for-credit ballet course.

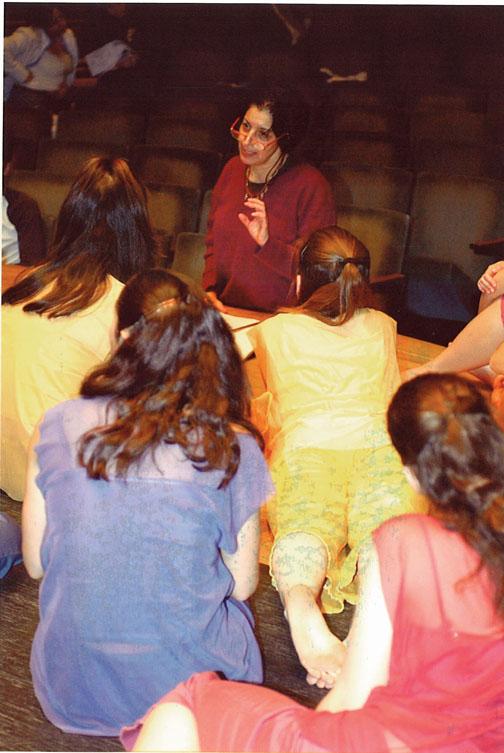

Cohen says she strove to help dancers and non-dancers alike articulate their own vision with greater clarity. “One of the gifts Ze’eva gives students,” says choreographer Mariah Steele ’06, “is to open them up so they can find their own voice — in dance, in choreography, and then that translates into life.”

Maria LoBiondo is a frequent contributor to PAW.

In a similar way, Cohen came to Princeton in 1969 with a vision of bringing instruction to each class not only in dance movement, but in choreography and critical writing as well — improvising with the resources available until, 40 years later, the seed has blossomed. Today a professor of dance, Cohen will retire in June.

Cohen’s multidisciplinary approach transformed two generations of students, ranging from novices who had no idea what a plié was to those with ballet barre training.

“Ze’eva changed lives in the studio,” says Jill Sigman ’89 *98, a choreographer who has performed with Cohen. “For some it was through simply sharing the joy of moving and the value of a physical existence in the world. For some it was about making connections between dance and other fields of study. For some, like myself, it was about revolutionizing their aesthetics.”

In recognition of Cohen’s achievements as a dancer, choreographer, teacher, and head of dance for nearly 40 years, the Lewis Center for the Arts is sponsoring a tribute April 3 at 6 p.m. in McCarter Theatre Center’s Berlind Theatre. Utah’s Repertory Dance Theatre will perform two Cohen-choreographed works: “Rainwood,” a signature piece, and “Ariadne.” Seven alumni will dance “Wig Wise,” a Cohen piece set to Duke Ellington’s music. Also on the program is a decade-by-decade photo retrospective of dance at Princeton.

Cohen’s first noncredit class (it became a for-credit course in 1971) was in modern dance — she says it provided an accessible starting point for a wide range of students.

Since then, Princeton’s dance program has grown to nearly a dozen courses in movement, choreography, dance history, and performance, taught by 13 faculty members and guest artists. With the division of the Program in Theater and Dance into two separate entities last year, and Susan Marshall’s arrival in September as the first director of dance, Cohen’s foundational work has evolved to a new level.

An established performer before teaching at Princeton, Israeli-born Cohen came to the United States in 1963, trained at Juilliard, and danced with the Anna Sokolow Dance Company, as well as with other troupes.

Cohen then branched out with what was, at the time, a trailblazing concept — a one-woman show of works by different choreographers. For a dozen years she toured internationally before starting her own dance company.

She taught part time at Princeton when she was not on the road. Fifty of the 60 students who enrolled in her first course were men, and the first performance, “To Dance Is To Live,” was an outdoor Earth Day celebration on Poe Field. In 1974 the Program in Theater and Dance was established under the umbrella of the Humanities Council, which allowed undergraduates to work for a certificate (the program now is part of the Lewis Center). The introductory course affectionately became known as “Dance for Klutzes.”

In the 1990s Cohen began teaching full time, and Princeton’s dance program adapted to the changing needs of undergraduates. The gender balance shifted, and students with years of training behind them began to clamor for more classes devoted to technique. This spring, for the first time, Princeton is offering a for-credit ballet course.

Cohen says she strove to help dancers and non-dancers alike articulate their own vision with greater clarity. “One of the gifts Ze’eva gives students,” says choreographer Mariah Steele ’06, “is to open them up so they can find their own voice — in dance, in choreography, and then that translates into life.”

Maria LoBiondo is a frequent contributor to PAW.