If one weakness of today’s politics is unrelenting shouting, that is not a sin that afflicts Jim Leach ’64, a former 15-term Iowa congressman and now head of the National Endowment for the Humanities. “Mild-mannered” is a term that seems to have been created to describe Leach. He speaks calmly, often in little more than a whisper, and shows an eagerness to listen that is not always common in career politicians. His office in Washington’s refurbished Post Office building is filled with painted wooden cutouts of famous iconoclasts, among them Rep. Jeannette Rankin, the only member of Congress to vote against U.S. participation in both world wars; Henry Wallace, vice president under Franklin Roosevelt, who lost his place on the ticket to Harry Truman after disagreeing with high-ranking members of his party; and Chief Black Hawk of the Sauk nation.

As a congressman, Leach refused to accept PAC money or out-of-state contributions and was so adamantly opposed to negative campaigning that during his 2006 re-election campaign (which he lost), he called his opponent to apologize for mailings sent out by the national GOP and threatened to leave the Republican caucus if they continued. After leaving office, he took turns teaching at Princeton and at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. This is a man whose official House portrait shows him wearing a sweater vest under his tweed jacket. In mien and manner, he screams the word “professorial” — or he would, were it not so hard to imagine Jim Leach screaming anything.

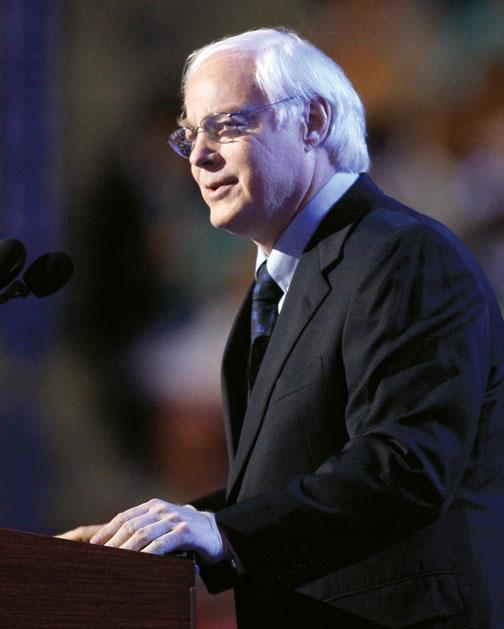

SO IT IS NOT SURPRISING that Leach has chosen to address the growing problem of incivility in our public life. As NEH chairman, he has embarked upon a 50-state “American Civility Tour” meant to raise awareness of the issue around the nation. He also made it the theme of his address at Alexander Hall on Alumni Day in February, when he accepted the Woodrow Wilson Award, Princeton’s top award for an undergraduate alum.

“The times,” Leach declared, “require a new social compact rooted in mutual respect and citizen trust.” Civility, however, is more than simple politeness, although such courtesies are certainly a part of it. “At its core,” Leach explained, “civility requires respectful engagement: a willingness to consider other views and place them in the context of history and life experiences.”

Recent incidents of public incivility abound. Right-wing talk radio hosts tar President Barack Obama as a “socialist.” Some liberal bloggers label former Vice President Dick Cheney a “fascist.” When the president appeared before a joint session of Congress last fall and said that his health-care plan would not provide benefits to illegal aliens, Rep. Joe Wilson, R-S.C., shouted out, “You lie!” The House slapped Wilson with a resolution of disapproval, but he also reportedly raked in campaign donations from those who applauded his misbehavior.

By historical standards, this is not much. We live in a country in which the sitting vice president, Aaron Burr 1772, killed the former treasury secretary, Alexander Hamilton, in a duel, and where half a century later, South Carolina Rep. Preston Brooks clubbed Massachusetts Sen. Charles Sumner with a gold-tipped cane on the Senate floor. Newspapers from the beginning of the republic were sharp-elbowed and nakedly partisan, without bothering to drape it with the “We report, you decide” mantle. But a more recent period of relative comity seems to have ended.

Behavior such as Joe Wilson’s would have been inconceivable a decade ago, says former Oklahoma Rep. Mickey Edwards, a Republican, who is now vice president of the Aspen Institute and a visiting lecturer in the Woodrow Wilson School. “We would never have had someone say, ‘You lie!’ during a presidential speech. Not because it shows a lack of deference to the president, but because at the time, the president was speaking as a guest of the institution. It violated the rules of decorum.”

This decline in decorum, which Leach also witnessed firsthand, prompted him to speak up about it when he took over at the NEH. Incendiary words matter, he insists, because calling someone a “socialist” or a “fascist” is not an argument, but a label that serves as a substitute for thought. The words we use, Leach explained in his Alumni Day address, “clarify — or cloud — thought and energize action, sometimes bringing out the better angels of our nature, sometimes baser instincts. When coupled with character assassination, polarizing rhetoric can exacerbate intolerance and perhaps impel violence.”

But, as Leach observes, incivility also takes a more insidious form in the tactical refusal to engage those with differing opinions in a search for the common good. The day after Congress passed health-care reform, for example, Arizona Sen. John McCain declared that the Republicans would not cooperate with the Democrats on any more legislation during this term, no matter what the issue. Both John Boehner and Mitch McConnell, the Republican leaders in the House and Senate, have described their caucus’s strategy as simply denying the Democrats a victory.

In theory, at least, civility should not be incompatible with partisanship. People ought to be able to argue vigorously without being uncivil about it. That is one of the reasons why Congress adheres to an elaborately deferential code of conduct in which members call each other “my good friend from Utah,” “the distinguished member from Ohio,” and the like.

Although such superficial niceties still prevail, they mask deepening problems. “Partisanship that refuses to see anything in another’s thought processes that might have some bearing on his own is very foolish,” Leach says in an interview. “If the Republican argument is ‘no victory’ [for Democrats], you have a system that becomes closer to nihilism but not quite, but certainly much closer to a European political system.” Such zero-sum calculations — if you win, I lose — are more routine in parliamentary systems, but those systems also give a willful minority much less power than minority-party members have in the United States — such as the filibuster or the hold a single senator can put on a nomination — to impede the majority from getting its way.

Today, the two parties seem to exist in different worlds. Each Senate office, for example, receives its own closed-circuit television feed of the proceedings on the floor. Republicans receive a feed from the Republican caucus that contains information about what is being debated and, in some situations, how the members are expected to vote. Democrats receive something similar from their caucus. In this sense, members of different parties literally are not even watching the same debate.

Jim Marshall ’72, a Georgia Democrat who has been in the U.S. House of Representatives since 2003, thinks that things have gotten worse since President Obama took office last year. Leach and others date the rising level of vitriol to the early ’90s, when a new generation of aggressively partisan conservatives under Newt Gingrich’s leadership took control of the House Republican caucus. Edwards suggests that the Gingrich group may have been retaliating for slights inflicted by the Democrats when Jim Wright was House Speaker. Still others date the era of bad feelings to Robert Bork’s Supreme Court confirmation hearings in 1987, which ended in the Senate rejecting his confirmation.

IN MANY RESPECTS, however, political incivility may reflect a broader fragmentation in American society. Civility has its root in the Latin word for “citizen” — civis — and in that sense, civility carries with it a shared sense of identity. Leach suggests that the rise in incivility may follow a weakening of that shared identity.

These days, anyone can start a blog or a Web site and reach an audience; the limit is only one’s marketing skills. Fifty years ago, the John Birch Society did not have the same capacity to reach a national audience as the Internet gives to hate groups today, a development that Marshall says has contributed to the proliferation of “niche weirdness.” When there were only three television networks and a half hour of national news each night, Walter Cronkite and Chet Huntley had to cater to a more heterogeneous audience than do today’s cable outlets. More of us now choose to exist within our own informational echo chambers, in which conservatives turn to Fox News while liberal politicos tune in to Keith Olbermann or Rachel Maddow at MSNBC.

“If the news comes on and you’re not interested in hearing news like that,” Marshall says, “you can change to find news that you want to hear. ... What we tend to do is go to the blogs or news sources that reinforce our own beliefs.” That increases people’s certainty that what they hear is right, because it is all they hear.

Sean Wilentz, the Sidney and Ruth Lapidus Professor in the American Revolutionary Era, suggests that the increase in political incivility reflects a broader coarsening of the culture. Just think about the once-forbidden words that now sprinkle casual conversation or the types of things that might be shouted during a sporting event or at another motorist. However, he suggests that things be kept in perspective. “No one has called anyone out for a duel lately,” he observes. Nevertheless, he agrees that the breach between the parties is much wider today than it was even, say, at the height of the debate over civil-rights legislation in 1964.

Polls suggest that the country itself is not as bitterly divided as Congress or the media say it is. That raises the question whether some of the vitriol is just a marketing ploy. Perhaps the only way to be heard above the media din is to shout.

“If you don’t have anything substantive to say, you can call somebody a name,” asserts Christopher “Kit” Bond ’60, who is retiring this year after four terms as a Republican senator from Missouri. Bond is one of those senators who has been able to remain a dogged partisan while maintaining good working relations across the aisle, something that seems attributable to his own sense of decency. With a little embarrassment, he tells a story of the time when former New York Sen. Daniel Patrick Moynihan, a Democrat, slugged him on the Senate floor after Bond denounced an earmark Moynihan had slipped into a highway appropriations bill. Some months later Moynihan apologized, and the two occasionally would relax in Moynihan’s office after a long day to discuss their shared interest in urban renewal over a glass of port.

It might be nice to think that some of the outrage is stage-managed, like professional wrestling, but Juliet Eilperin ’92, a political writer for The Washington Post, thinks most of it is all too real. “The fact that lawmakers don’t know each other as well as they used to has led to some of their misperceptions about each other,” says Eilperin, who chronicled the Gingrich revolution in her 2006 book, Fight Club Politics: How Partisanship Is Poisoning the House of Representatives (Rowman & Littlefield). “Many of them actually do think that their opponents are evil.”

Marshall tells a story about leaving the Capitol one day with a fellow Democrat from another state, whom he would not name. They passed another member of the Georgia delegation, a Republican, and Marshall said hello to him. “Was that a member of Congress?” the Democrat asked. “Oh, it must have been a Republican. I decided before I got here that I did not need to learn the names of any Republicans.”

Some look back nostalgically to the days when members of both parties, like Bond and Moynihan, would meet for a friendly drink or game of poker. In the House, certainly, and to a large degree in the Senate, as well, those days are gone, because the institution of Congress has changed. It is easier for members to return home on weekends rather than stay in Washington. Even when they are in the capital, there are so many committee hearings to lead, fundraisers to attend, and visiting constituents to meet that members have little or no time to socialize. “Each congressional office becomes a cul-de-sac in a neighborhood,” Leach says, “and it is hard to get out of that cul-de-sac.”

In the House, he explains, technology has taken much

of the guesswork out of redistricting. Most congressional seats today have been deliberately drawn to make them safe for one party or the other. If that is the case, a Democrat has less to fear in the general election than in the primary, when he or she might be attacked from the left. Republicans would have similar fears about a challenge from the right. There is much less incentive for members to seek common ground across the aisle and much more to guard their flanks.

Leach thinks this problem could be addressed by removing the redistricting process from the state legislatures and entrusting it to a nonpartisan body, as is done in Iowa. Eilperin advanced a similar prescription in her book. But neither thinks that this would entirely fix the problem. There has been a great regional sorting out in our politics that has made each party more ideologically pure and thus more isolated from the other. Today, for example, there is not a single Republican member of the House from New England and hardly any white Democrats from the South (although Marshall is a rare, and perennially endangered, example). Changing the redistricting process also would do nothing about incivility in the Senate.

This acrimony, too, shall pass, Wilentz thinks, as some of the political issues that drive it — health-care reform, anti-terrorism policy, financial regulation, deficit reduction, and so on — become less salient over time. But not just yet, he says: “I don’t see it going away anytime soon.”

Edwards questions whether the solution is to try to pull everyone back toward the middle. “The whole job of representing is to represent the views of your constituents,” he explains. “Democracy is not about everyone having a centrist view. But it is about having a good, serious consideration of other possibilities. We don’t need consensus, but compromise.”

To date, Leach’s civility tour has reached about a dozen states, though he plans to get to all of them eventually. He does not have any illusions that it will fix the problem, though he does hope that it will draw attention to it and his talks have been well received. Leach also has pushed an NEH initiative called “Bridging Cultures,” which seeks to increase understanding of people in different places and times. He has criticized the recent Supreme Court decision striking down limits on corporate campaign contributions, which he says may inflame incivility by increasing corporate influence and making it harder for marginal voices to be heard. “Moneyed speech that carries strings may be the most uncivil speech of all,” he said at Alumni Day. “It eviscerates reasonableness in public dialogue and distorts the capacity of citizens and policymakers to weigh competing views in balanced ways.”

In her book, Eilperin quotes then-Rep. Richard Gephardt, a Democrat who served as both majority and minority leader in the House. He suggested that civility would return only if the voters demanded it. “The voters,” Gephardt told Eilperin, “will ultimately judge if they’re getting what they want or what they need.” Congress’s abysmally low approval ratings suggest that the public is far from satisfied. Leach hopes that the most effective voices will be the ones that belong to speakers who do not shout, but reason and listen.

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.