In baseball, thinking too much is a liability.

Last month alone, major leaguers cited over-thinking for nearly every conceivable flaw, from erratic pitching (San Francisco’s Tim Lincecum and Texas’ Rich Harden) and a long hitting slump (Oakland’s Jack Cust) to unsuccessful base-running (Minnesota’s Denard Span).

Baseball is awash with data, sorted and studied in nearly every conceivable way. Fans can go online to find, for instance, how often their favorite player swings at a pitch when the count is three balls and one strike. Pro players see the same sort of information — and more — in scouting reports.

So how does Ross Ohlendorf ’05, an operations research and financial engineering graduate and starting pitcher for the Pittsburgh Pirates, deal with the deluge of data? Carefully, he says.

Ohlendorf occasionally finds a useful trend in his own statistics. Last year, left-handed hitters were having trouble hitting his slider but handling his changeup, so he started throwing more of the former. Before each game, Ohlendorf studies statistics about opposing batters to develop a basic game plan.

But there’s a downside. The most important thing, Ohlendorf says, “is executing your pitches and throwing them where you want to. Sometimes I’ve fallen into that trap of thinking too much. It’s something that I’ve learned to manage.”

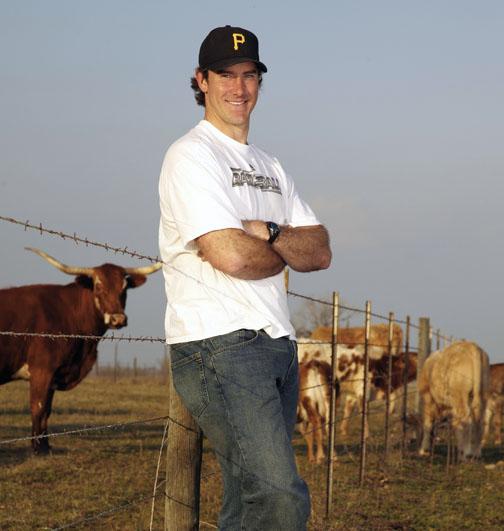

Ohlendorf is a rising star on the diamond — in nearly two full seasons with the Pirates, the hard-throwing right-hander has emerged as one of Pittsburgh’s most reliable pitchers — though he hasn’t been able to turn around the Pirates dismal record. He’s also — according to ESPN baseball analyst Tim Kurkjian, at least — the “smartest player in baseball,” and he has plenty of avenues for exercising his mind. In baseball’s offseason, he manages business operations with his father and brother at the family’s longhorn cattle ranch near Austin, Texas. Last year, Ohlendorf learned about farm policy from the government’s side of the desk as an intern at the Department of Agriculture in Washington, D.C.

His talent, interests, and Princeton pedigree have made him a top attraction on a team with few household names. Sports Illustrated’s Mark Bechtel joked that Ohlendorf is “just another Princeton-educated rancher who throws in the mid-90s and fell one question short of acing the math SAT.” In the same article, former Pirates pitching coach Joe Kerrigan compared Ohlendorf to another Princeton scholar-athlete, Bill Bradley ’65, and Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack suggested that the young pitcher might be an attractive political candidate one day.

Ohlendorf says that he’s stopped reading his clippings and dislikes being in the spotlight. “Some of my interests are a little bit different,” he concedes. “But I don’t want to feel too different, and I don’t feel like I am too different.”

A major league clubhouse is one of the few workplaces on earth where a broad-shouldered, trunk-legged, 6-foot-4-inch man who flings a ball 95 miles per hour might not be considered “too different.” Ohlendorf’s teammates agree that he’s a regular guy — with a few subtle quirks. He’s better than average at crosswords, and he reads more than his share of books (“mysteries, mostly — very light reading,” he says). When the pitchers kill time in the dugout by calculating batting averages in their heads, Ohlendorf is the only one who can accurately estimate three decimals. “You can tell he has a higher education than most,” says teammate Daniel McCutchen, a University of Oklahoma grad.

Princeton baseball coach Scott Bradley, a former major league catcher, says that Ohlendorf has a tireless work ethic, instilled by his ranch upbringing, but Ohlendorf is quick to note that he wasn’t raised on the ranch. He grew up in Austin, a city of nearly 800,000 people, where both parents worked in administrative jobs at the University of Texas. His mother, Patti, is the university’s vice president for institutional relations and legal affairs. His father, Curtis, is retired from the library’s IT department. The family started raising longhorns during Ross’ teen years on land that his paternal grandfather once farmed, about a half-hour outside of Austin. The herd has grown to about 300 head of cattle, and Curtis Ohlendorf says his son has a “natural cow sense” to move the animals along.

Ranching is the one topic that Ohlendorf never tires of discussing, says Princeton roommate Paul Ackerman ’05. “After you get the 30-minute overview from Ross,” he says, “you want to know everything there is to know about raising longhorns.”

For example, the young pitcher has plenty of thoughts on the best way to photograph cattle — important in the longhorn business because many potential buyers start their shopping online. The website for the Ohlendorfs’ Rocking O Ranch displays rows of perfectly posed animals, heads facing the camera with their bodies in profile. Taking those pictures requires the right lighting — early morning and late afternoon work best, Ohlendorf says — and a bit of practice. “You have to squat down and have some patience,” he says. “Some are more apt to look at you the whole time, and others couldn’t care less what you’re doing. They just stand there and eat.” Working outdoors is part of the draw, but Ohlendorf also enjoys the business dynamics of running a ranch: In addition to updating the Rocking O website, he helps make decisions about which animals to keep, which to sell, and how to set prices.

Ohlendorf chose Princeton over Harvard partly because he wanted to major in operations research and financial engineering (ORFE), and as a freshman, he studied chemistry alongside the premed students, even though it had little to do with his intended major. Ackerman, now a neurosurgery resident at Loyola University Medical Center in Chicago, remembers studying for the freshman chemistry final with Ohlendorf, going chapter by chapter through the textbook and reviewing everything that could be on the exam. When they got their grades, it was Ohlendorf, the math whiz, who answered the final question that had stumped most of the class. Ackerman wanted to know how he knew the right formula. “I just derived it,” Ohlendorf said. “It’s the only thing that made sense.”

Nine years after first encountering Ohlendorf in a freshman seminar about issues in intercollegiate athletics, Harold Feiveson, a senior research policy analyst at the Woodrow Wilson School, still recalls the future major leaguer’s work. A major class paper, he remembers, dealt with the “Chris Young rule,” the Ivy League’s decree that prohibits a professional athlete in one sport from competing collegiately in another. (Young had to give up his Princeton basketball career after going pro in baseball.)

Ohlendorf, who had toyed with the idea of playing two sports at Princeton, was sympathetic with Young’s situation. But his research, which included an interview with former Princeton president Harold T. Shapiro *64, also explained the Ivy presidents’ viewpoint in careful detail. “He was very good at trying to understand the arguments from the other side,” Feiveson says of Ohlendorf. “Sometimes, you take a position and you become an advocate. With Ross, it was more reflective.” In the end, the pitcher effectively refuted the league’s logic.

Drafted by the Arizona Diamondbacks at the end of his junior year, Ohlendorf started his pro baseball career early and split his senior year into two fall semesters to accommodate spring training. While negotiating his first contract — a monthly salary of $1,000, plus $280,000 in bonus money — Ohlendorf came to realize just how important a young player’s signing bonus could be, given the relatively low salaries that players earn in the minor leagues.

His 140-page thesis examined how the bonus investments compared with the long-term returns that teams earned as their draftees developed into major leaguers, and on average, Ohlendorf found, the teams fared quite well — the average draftee does not earn what he’s worth. That’s especially true for later draft picks who reach the major leagues. (Ohlendorf, who does not yet qualify for salary arbitration or free agency, is slated to earn $439,000 this year — a hefty salary for a 28-year-old, but a free-agent pitcher with similar skills might earn 10 times as much.)

If Ohlendorf was miffed by the realization that players are underpaid, he didn’t let it show in his thesis. Even now, when Ohlendorf discusses the project, he talks about the economic mechanisms at work — a “controlled market” in which a player’s only choices are to sign with the team that drafts him or sit out and wait for a year until the next draft. Mike Chernoff ’03, the director of baseball operations for the Cleveland Indians and a former Princeton teammate of Ohlendorf, says that the thesis was on par with research from analysts who work in major league front offices.

Ohlendorf’s latest challenge was a brief foray into government, paved in part by his baseball connections. Last season Vilsack, a former governor of Iowa, returned to his native Pittsburgh to throw out the first pitch at a Pirates game. Ohlendorf took the opportunity to chat with the agriculture secretary, and after sending off his résumé and talking with a few of Vilsack’s colleagues, he landed a part-time, unpaid internship at the agriculture department starting last October.

During his 10 weeks in Washington, Ohlendorf returned to his academic roots, delving into economic analyses of department programs and flying under the radar, with one notable exception — traveling with Vilsack and first lady Michelle Obama ’85 to an event that promoted healthy eating and physical activity for children. In February, as spring training approached, baseball writers picked up the story; Ohlendorf, a bit surprised by the attention, told The New York Times: “If there are things that interest me, and I am interested in a lot of things, I try to make an effort to learn more about them.”

Ohlendorf had arrived at Princeton with a fastball that already reached the mid-90s on the radar gun, and each year, he improved his control and refined his pitches. As a freshman, he earned a spot in the Tigers’ starting rotation, and in his sophomore and junior seasons, he was the staff ace on a pair of Ivy League championship teams. Former teammates say that Ohlendorf was among the team’s best all-around athletes. In batting practice, he would launch towering home runs (a trait that has carried over to the majors, though he’s yet to hit one in a game), and in pick-up basketball games, he showed off the shooting skills that had made him an all-state player in high school.

Bradley, who has mentored more than a dozen future pros, is happy to talk about Ohlendorf as a pitcher — his explosive delivery, the way he “just overpowers a baseball.” But his favorite story about Ohlendorf doesn’t even involve baseball:

It was Ohlendorf’s freshman year, on a morning after a lacrosse game, and the baseball players were scheduled to pick up trash at Class of 1952 Stadium — a common way for athletics programs to earn a little extra money for their travel budgets. Most of the players wandered downhill in jeans, but Ohlendorf jogged to the stadium in sweats, looking like he was ready for a scrimmage. And in the hour that followed, he cleaned with a Paul Bunyan-esque fervor that still brings a smile to Bradley’s face.

“He treated it like it was going to be his game day,” the coach says. “He was literally running from garbage can to garbage can, flinging bags of garbage over his shoulders.” The message to his teammates was easy to absorb: Nothing was beneath Ohlendorf, and whatever the task, he was going to be the best at it.

After leaving college baseball in 2004, Ohlendorf steadily climbed the ladder of the minor leagues, earning his first major league call-up as a relief pitcher for the New York Yankees in September 2007. He had every reason to be star-struck: His teammates included a string of surefire Hall-of-Famers like Alex Rodriguez, Derek Jeter, and Mariano Rivera, and the Yankees were in the midst of a tense pennant race with the Boston Red Sox. When the team’s playoff run ended a month later, Ohlendorf cleaned out his locker, packed his car, and began driving back to Austin. “That was when I really started to think about how cool the last month had been,” he says. “While at Princeton, I went to a couple of Yankees playoff games. Three years later, I was sitting in the bullpen.”

But his time in pinstripes would be short-lived. The following year, Ohlendorf was traded from the Yankees, one of baseball’s elite teams, to the Pirates, a once-powerful franchise with 18 consecutive losing seasons — the worst record of any U.S. pro team in history. In recent years, the Pirates have tried to rebuild with young talent, and Ohlendorf was part of that strategy. On balance, it’s been a positive move: In New York, he seemed destined for bullpen duty. In Pittsburgh, he has been able to prove himself as a major league starter. He posted a 3.92 earned-run average in 2009, best among the team’s starters, and was one of the team’s two leading pitchers, each with 11 wins. This season has been less successful, in part because of anemic support from the Pirates’ offense. Ohlendorf won just one of his first 12 decisions, but he has improved his strikeout rate and maintained a respectable 4.07 ERA.

In the minor leagues, scouts were surprised to find that the velocity of Ohlendorf’s pitches actually increased near the end of the season, and this August, he seemed to be peaking late again. But that changed quickly Aug. 23 when Ohlendorf felt soreness in his shoulder and left his start against St. Louis after just eight pitches. The injury, diagnosed as a strained muscle, sent Ohlendorf to the disabled list, likely ending his season.

Ohlendorf hasn’t pinned down what he’ll do during this offseason, and he’s in no rush to move on from his current career. If he hadn’t been drafted, he probably would have gone to Wall Street, like many of his ORFE friends. He also can imagine himself back in Washington — the agriculture department internship sparked an enduring interest in government. He hopes to remain involved in the ranching business and return to school to study business, law, or both. Staying in baseball, on the management side, is an appealing path, too; as the Pirates’ alternate representative for the players’ union, he will sit in on meetings about baseball’s next collective-bargaining agreement.

He’s happy in Pittsburgh, where he can walk to the ballpark from his apartment downtown. He loves the major league lifestyle, traveling from city to city in chartered airplanes and staying at top-notch hotels.

“Most other jobs I can do when I’m older,” Ohlendorf says. “Baseball, just from a body-aging standpoint, I can only do for so long. ... I’d like to be able to continue to do it for a while.”

Brett Tomlinson is an associate editor at PAW.

Chris Young ’02

THESIS TITLE: “The Integration of Professional Baseball and Racial Attitudes in America: A Study in Stereotype Change”

SYNOPSIS: Did Jackie Robinson’s integration of professional baseball in 1947 indirectly shape racial attitudes and stereotypes in America? Young, a politics major, hypothesized that since segregation in the 1940s limited contact between whites and blacks, much of what whites knew or believed about African-Americans was shaped by newspapers. He studied New York Times stories in the three months before Robinson’s debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers and the three months afterward. In the post-integration period there were more stories about African-Americans. The percentage of negative stories dropped significantly, and the percentage of neutral stories increased. The proportion of positive stories rose slightly. “The intriguing part of this study is that such a significant change in media content was observed despite the fact that all sports-related articles were excluded,” Young wrote. The data supported the idea that Robinson’s short-term contributions reached well beyond baseball.

PERSONAL TIE: On April 15, 2007, when Major League Baseball celebrated the 60th anniversary of Robinson’s debut, Young took the mound for the San Diego Padres against the Los Angeles Dodgers. The Dodgers, with each player wearing Robinson’s No. 42 jersey, won the game, 9–3.

Ross Ohlendorf ’05

THESIS TITLE: “Investing in Prospects: A Look at the Financial Successes of Major League Baseball Rule IV Drafts from 1989 to 1993”

SYNOPSIS: Minor league baseball players earn minimal salaries — currently $1,100 per month for first-year players — but are compensated up front with seemingly generous signing bonuses. First-round picks can earn millions before they even lace up their cleats. The draftees then are committed to one team for several years under baseball’s “reserve clause,” and when they reach the majors, they generally earn the league’s minimum salary for their first three seasons. Do teams profit from this system? Yes, according to Ohlendorf’s economic analysis, which tracked 500 top draft picks. By comparing the cost of paying each player with the cost of paying a comparable free agent, Ohlendorf found that on average, teams earned a 60 percent return on their bonus and salary investments. Draftees have come to expect bonuses, based on what was paid in previous years, but if those bonuses never existed, Ohlendorf says, “most players would probably sign for free.”

PERSONAL TIE: Ohlendorf’s work was sparked by clubhouse conversations with minor league teammates who believed that signing bonuses were too high for the top picks and too low for players chosen in later rounds.

Will Venable ’05

THESIS TITLE: “The Game and Community: An Anthropological Look at Baseball in America and Japan”

SYNOPSIS: Venable’s thesis compared American and Japanese culture by presenting histories of baseball’s evolution in each country. He included an exploration of how the affinity for baseball is passed from generation to generation, showing how communities form around the game at different levels of society. But the most interesting reading is in his detailed descriptions of how the game is played and practiced. He drew parallels between Japan’s corporate culture and the work ethic instilled on the baseball diamond. For Japanese pros, a typical spring-training day begins at 7:30 a.m. and concludes with lectures and indoor practices in the evenings. In between, players are pushed to exhaustion by drills designed to build a fielder’s fighting spirit. “The proper spirit is believed to be the key to ultimate success,” Venable wrote, “and attainment of spirit comes through hours and hours of repetition.”

PERSONAL TIE: Venable spent part of his childhood in Japan, where his dad was a “gaijin” (foreign player) in the Japanese professional baseball league. The younger Venable experienced Japan’s baseball culture while playing for a local Little League team, enduring marathon practices in the summer months.