I arrived in Dachau on April 29, 1945, as part of the 20th Armored Division, which helped to liberate the awful concentration camp there. Sixty-five years later, on April 29, 2010, I returned as the representative of the 7th Army, whose three divisions – the 42nd, 45th, and 20th – liberated the camp. In 1945, as a private first class, I entered the camp briefly; in 2010 I sat next to the president of Germany. In 1945 I saw poor emaciated skeletons of crazed prisoners trying to hug me; this year I returned to greet several hundred citizens from all over Europe, still hugging me. During the war I was a young GI, scared and ready to combat the German army; in April 2010 I sat next to a German colonel who helped translate for me an article about Dachau in the Munich paper.

A Dachau anniversary many years later is a unique affair. Each former prisoner has a story to tell. Many returned, hoping to find old cellmates. This seldom happened, but many made new friends, all bound together by the hardships they had endured. One Frenchman told me how he and 15 others were ordered to destroy food supplies by dumping them in the stream around the camp, a sort of moat – despite the fact that that all 15 were starving and dying of hunger. Suddenly they jumped the one SS guard, hiding in the woods until they were rescued a few days later by the Americans.

Another prisoner, a former German opposition leader who spent seven years in the camp, described the death march through Munich designed to send the remaining ambulatory prisoners up into the Tyrol, where the Nazis vainly hoped to make a last stand. A French friend recounted how those who fell behind were summarily executed by the Nazi SS guards. On this marche au mort the prisoners had to push carts full of civilian clothes so that the SS guards could shed their uniforms and fade into the local villages. Suddenly, at a signal, the French on this march killed all the remaining guards and took over local homes while awaiting the Americans’ arrival.

Another Frenchman told us how he and a small group of deportees were jammed into a railroad car en route to Dachau when the car was abandoned in a gulley and became a target for Allied bombers who thought it was a German troop train. The French prisoners ripped their clothing apart and fabricated a tricolor, which they put on the top of their car. Later they thought they would all be executed if left there, as the train could not move. Fortunately, my French friend and another prisoner managed to slip through the German lines and arrived at an American outpost. There they identified themselves, not easy with prison garb on, and persuaded their American friends to return to the train with a bulldozer, pulling the former cattle car back to safety.

Dozens of conversations over this 65th anniversary revealed remarkable feats of courage by former prisoners. Curiously, however, there seemed little bitterness versus the current German population. The survivors knew that there were enormous differences between their Nazi captors and the many German victims of the regime. Furthermore, German politicians, schoolteachers, and many survivors all have exhorted German youths never to fall for extremists, right or left, in the future. A new visitors center and updated museum show graphic pictures of the camp in 1945, impressing the hundreds of visitors how horrible conditions were then.

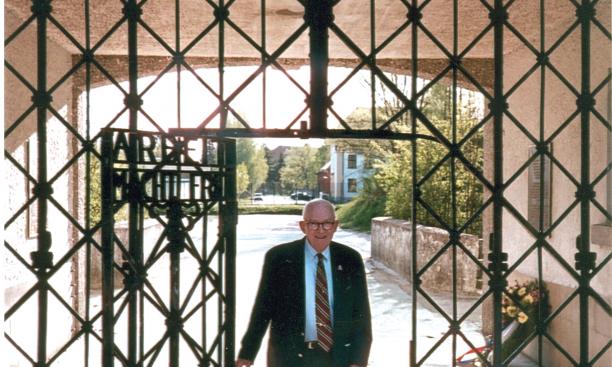

On April 29, the exact anniversary, I was invited to speak to a group of some 30 survivors at the entrance to Dachau where the infamous sign – Arbeit macht frei (Work makes you free) – is still implanted over the entry doorway. The sign is particularly nasty and ironic when applied to the prisoners who were forced to do hard labor. Half of this group were French; the others Dutch, Danes, and Israelis, so I spoke in English and French. This was followed by a solemn ceremony where I placed a wreath below the 20th Armored plaque, which I had helped to install after the 50th anniversary in 1995. Another plaque to the 42nd Division shares the entrance to this terrible camp.

After this ceremony, we were all invited to the museum auditorium for a rather unusual event. It happened that during the four months preceding the liberation, seven pregnant women were kept in one room as they cooked for the SS guards. Their husbands had been executed in December 1944 but the wives were spared, as they were cooks. During the next four months they all gave birth in the same room, sharing milk and other bare essentials. After they were liberated, they all disappeared until two young German ladies decided to track them down. Finally, all seven were found; only one mother is still alive, and she spoke to us by video. The “seven babies,” as they were described, were brought back to Dachau for this anniversary, and they are all 65 years of age.

The leader, a well-known Toronto doctor whom I was sitting next to, was amazed that he had been found. There was a Brazilian businessman who could speak only Portuguese. The others, all women, were from Eastern Europe, speaking Polish, Rumanian, or Czech. Each told his or her story that will be included in a film series, designed to cover the expenses of finding the “babies” and bringing them back to Dachau. I was present the next day when all of the 65-year-olds were invited to become honorary members of the International Committee for Dachau (CID).

The former president of the CID was Gen. Andre Delpeche, the leader of the French prisoners who killed the guards on April 29 as we entered the camp. He was then a captain, and he remained in the French army afterward. I had come to know him well in 1995 and 2005, but at 89 he could not attend the anniversary events this year. He was succeeded as president by Pieter Dientz de Loos, a Dutch lawyer whose late father had been a Dachau survivor. The CID has branches in most European countries, and I was invited to join as the first American member with the possibility of setting up an American branch.

Early on Sunday, May 2, we all attended an ecumenical service in the large Catholic chapel at the far end of the camp, where there are Protestant, Jewish, and Russian Orthodox chapels as well. The Protestant chaplain gave the sermon in German, and I was very surprised to hear my name mentioned. The pastor later gave me an English version in which he said, “Alan Lukens and 30,000 other American soldiers shared their provisions with the 35,000 prisoners, in the same way that Jesus had fed 5,000 people with five loaves and two fish.” I was a little taken aback by this analogy, but I was the only American the pastor had met, since I had spoken to him and the Catholic priest the day before.

After the service we gathered in an enormous tent holding some 1,500 people, mostly survivors and their families, plus numerous official delegations from all over Europe. President Horst Kohler of Germany attended for the first time at Dachau, giving an inspiring speech. His very presence made a major statement. He abhorred the Nazi past, stressing that the new Germany was part and parcel of the democratic Europe. He was followed by Martin Zeil, Bavaria’s minister of economic affairs, and Karl Fuller, president of the Bavaria Foundation, both of whom echoed the same refrain as President Kohler.

Then came my turn as the liberator, speaking for the 30,000 members of the 7th Army forces. The only other American veteran there was Dee Eberhard, president of the 42nd Division, who was applauded when I asked him to stand. Fortunately, President Obama's message arrived just in time, so that I was able to include it in my remarks. President Kohler came over to me after my speech to thank me personally.

Following the speeches, about 100 wreaths were carried to the wall, similar to the Vietnam memorial in Washington, D.C. I contributed one from the 20th Armored Division, carried by my son and grandson. They also helped to carry the U.S. wreath offered by American Consul General Conrad Tribble and a special one given by my French survivor friends.

Following the official ceremonies at Dachau was a memorial event at Hebertshausen, a satellite of Dachau, where 4,000 Russian prisoners were executed in the fall of 1941 after the German attack on the Soviet Union. Later, in the main square of the city of Dachau, another service was held for 10 prisoners executed in cold blood by the Nazis only hours before the liberation. These were leaders of a movement in the camp to turn over the camp to us, who were caught by the SS guards just before we arrived.

After these special services everyone – survivors, their families, German and foreign officials, and we two veteran liberators – adjourned to a gigantic tent where ample wiener schnitzel and beer were offered to all by the German hosts, allowing us to relax and renew old friendships. I had attended the 50th anniversary in 1995 and the 60th in 2005, where there were many more American veterans. This 65th was even more moving, since so many survivors had managed to come even though most were in their late 80s.

Despite their age their minds remained razor-sharp, and they vividly remembered the worst aspects of their imprisonment and the joy and excitement of April 29, 1945, when we entered the camp.

This could be the last gathering to mark the anniversary, given the ages of both survivors and liberators. Nevertheless, the impressive Memorial Foundation, headed by Dr. Gabriele Hammermann, which includes the museum, visitors center, and the four chapels, has become a permanent fixture in Bavaria. The German authorities insist that all schoolchildren visit Dachau so that this disastrous part of German history not be forgotten by future generations. We must all keep in mind the motto of the Dachau Memorial: “Never Again.”

The 65th-anniversary commemoration of the liberation of the Dachau concentration camp will long be remembered by the survivors and by me. I was fortunate that my son and grandson were there to take part with me in this moving and emotional historic event.

Alan W. Lukens ’46 was a Foreign Service officer from 1951 to 1987.