Politicians are politicians everywhere, it seems, and for the most part the Navajo Nation is no exception.

The Navajos were electing a new president, and two days before the August primary, 200 people filed into a candidate forum at Monument Valley High School in Kayenta, Ariz. Seven of the 12 presidential hopefuls in attendance pressed the flesh and passed out slick campaign brochures. An eighth candidate, however, did things differently.

That candidate, Rex Lee Jim ’86, also had a small flier, his offering “A New Direction Together for a Stronger and Prosperous Navajo Nation.” But Jim’s flier was slipped inside the pages of his book of Navajo poetry, Saad (“Voice of Expression”). Within a few minutes, dozens of voters were poring over its pages.

Passing out books of poetry at a presidential debate is an unorthodox campaign strategy, to say the least. Jim did it, he says, to show that “here is a candidate who is creative and willing to expand the capacity of the [Navajo] language to embrace modern notions of literature.” Navajo is an oral language, and Jim is part of the first generation of Navajos to reduce it to writing and publish it, according to Alfred Bush, the longtime curator of the Princeton Collections of Western Americana.

Jim finished fourth in that presidential primary in August, but his political fortunes were revived less than two weeks later when one of the two finalists, Ben Shelly, the sitting vice president and something of a Navajo Tip O’Neill, tapped Jim to be his running mate. (Results of the Nov. 2 general election were not available for this issue of PAW.)

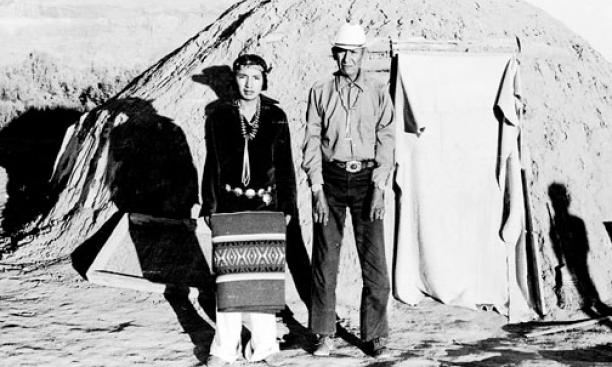

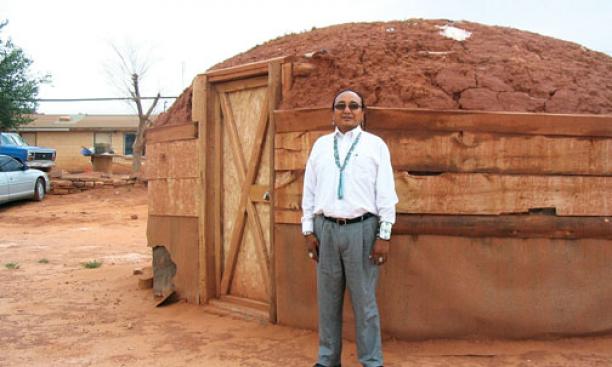

Jim — author, playwright, and medicine man — is unusual in the degree to which he keeps one foot in the traditional world and another in the wider world beyond it. He lives 15 miles by dirt road from the tiny village of Rock Point, Ariz., in a camp that lacks running water, yet he makes about 10 trips a year to Geneva, Switzerland, on United Nations business and more trips abroad as a representative of the Carter Foundation. He sits on the Navajo Nation Council, the tribe’s legislative body, where he chairs the public-safety committee. He campaigned every day in a uniform of dark sportcoat, dress pants, black lace-up shoes, and white dress shirt (along with Navajo jewelry), prompting the Navajo Times to write that he “could easily pass for a professor on the elite eastern campuses he once roamed.” Unlike any of the other candidates, he also wore his long hair in a traditional bun called a tsiyee. Though he is soft-spoken bordering on reticent, on the stump he declaims forcefully in fluent Navajo. Before the press conference at which Shelly and Jim made their first appearance as a team, the two candidates prayed together in a hogan, the traditional, round, mud-roofed Navajo dwelling. Then they posed for the standard political photograph with their clasped hands raised.

The traditional boundaries of the Navajo people are the four sacred mountains — Hesperus Peak, Blanca Peak, Mount Taylor, and the San Francisco Peak — but none of them sits within the lines of what is officially known as the Navajo Nation or Diné Bikéyah. Nomenclature among the Navajos is more a matter of taste than of political correctness: Many call themselves “Indian” (as does the federal government) and their home a “reservation,” but others prefer “Native American” or “Diné” (“The People”) and “Navajo Nation.” Even more, perhaps, refer to the area colloquially as “Navajoland” or simply “The Rez.”

Navajoland spans more than 26,000 square miles of northeastern Arizona, western New Mexico, and southern Utah, making it the largest Indian reservation in the United States, a territory that is larger than 10 of the 50 states. The Navajos are the country’s most populous tribe: According to the 2000 census, there were roughly 298,000 Navajos in the United States, about 174,000 of whom lived within the Navajo Nation. It is semi-autonomous, operating with a tripartite government and its own legal code, although one much proscribed by the Interior Department’s Bureau of Indian Affairs. There are constant reminders of the limits of the Navajos’ power: Its government can prosecute only misdemeanors, not felonies, and there is no private land ownership — Navajos lease their land from the federal government. This is, in part, to protect it from development, but the lack of clear title also makes it nearly impossible for Navajo businesses to get development loans.

This is ancestral land for the Navajos, but their history is a sad one. During the Civil War, federal troops rounded up more than 8,500 Navajos and moved them to a small prison camp in New Mexico. After an 1868 treaty permitted them to return to their territory, the Navajos largely were left alone until the discovery of oil on the reservation in the early 1920s led the Interior Department to institute a more organized form of tribal government.

In the summer, the roads of the Navajo Nation are filled with tourists on their way to Monument Valley, Canyon de Chelly, and the Four Corners. There is no more scenic area of the United States, nor are there many poorer ones. Almost one-third of all Navajo residences lack indoor plumbing or electricity. Sixty percent don’t have telephones. More than 40 percent of families live below the poverty line, and fewer than a quarter of the roads in the Navajo Nation are paved. School buses trying to pick up children who live outside the few small towns must negotiate paths that often are little more than ruts through the sagebrush. The unemployment rate, which is near 50 percent but runs as high as 85 percent in some places, has not gotten much worse during the recession simply because there were not many jobs to lose. Alcoholism is rampant.

Rex Lee Jim was born outside Rock Point, Ariz., in 1962, the fourth of eight children. His father was a farmer and a sheep and goat rancher; his mother, a housewife and weaver. As Navajos do, Jim introduces himself by identifying his ancestral clans: “I am of the Red House People, born for the Red Streak Running Into Water People. My maternal grandfather is of the Towering House People and my paternal grandfather is of the Mexican People.”

Jim concedes that the Navajo kinship system is complex. For traditional Navajos — the pull of tradition, Jim says, is weakening among the younger generation — clan identity determines many things, not least of which is whom a person may marry. Family relationships are a matter of clan identity rather than consanguinity. Navajos who never have met, for example, might consider themselves brother and sister, or father and son, because of their clan identities and their ages.

Traditional Navajo mores, Jim says, include strict rules of personal conduct, which were drummed into him when he was growing up, although such manners also are fading in influence these days. It is considered offensive for a woman to lie on her back in front of others or for men to lie on their stomachs, for example, because doing so carries sexual connotations. Physical contact in public is frowned upon, Jim explains, in part because of an ancient belief that the way for evil spirits to hurt a person was through his or her family. Kissing or even praising a child in public advertises to the spirits where a person is vulnerable; even now, Jim says, he greets his sisters only with a handshake. “Despite these elaborate restrictions, I do not feel deprived of the freedoms non-Navajos enjoy,” he wrote several years ago. “My parents taught and continue to remind me that what I grew up with is proper manners.”

Different family members have specific responsibilities in a child’s upbringing. Fathers, for example, teach boys the facts of life, as mothers do for daughters. Uncles, aunts, and grandparents pass along songs, chants, and stories. Jim’s maternal grandfather was a medicine man (the Navajo word — hatasi — means “singer”) and taught him the ancient ceremonies known as “blessingways,” keeping him out of school until the age of 8 to do so. Blessingways, Jim says, “are designed to address certain illnesses, whether spiritual, mental, or physical, so they require a certain set of knowledge and prayers. People come, they sing along, they pray with you.” He likens this form of crowd participation to cheering someone on at a basketball game. (Others have compared the longer blessingways, which can run for as long as nine days, to memorizing and then declaiming Wagner’s Ring cycle or the entire Old Testament in King James English.) Even when he was campaigning, Jim performed blessingways almost every weekend and on some weekdays, to mark a child’s birth or coming of age, when someone left to go into the armed forces or returned home, or “just when someone wants a blessed life,” he explains.

In addition to the traditional Navajo lore, Jim says, his grandfather passed along a restless curiosity. He lived to 102 and was still performing blessingways in his late 90s. Jim recalls lying next to his grandfather a few years before his death and caressing his hair. “My dear grandchild,” the old man said, “I wish I could live another 10 years so I could learn another song or two, or another ceremony.”

“He still wanted to learn, do more to help others more,” Jim recalls. “To me, that’s awesome. At that age, you don’t have to worry about material things. Your only concern is your own learning and improvement as a person, and then to channel that energy into helping others.”

Rock Point, population 724, is surrounded by red, striated cliffs and overlooks a farm-dotted valley through which a broad, muddy stream flows. As a boy, and even today, Jim would retreat to the promontory to look out across the valley for inspiration. But he also felt a tug toward the outside world, which was encouraged in the early 1970s by Sam and Janet Bingham, two journalists who had been driving to Boston and stopped in Rock Point, where they saw that the school was looking for teachers. The couple remained.

It’s 100 miles in any direction from Rock Point to the non-Navajo border towns where English is spoken, and Jim, like almost all the children of his generation, entered school speaking only Navajo. His older sister, Janice, who was working at a nursing home in Utah, would send him letters with English vocabulary words for him to study. Today, he says, the percentages are reversed, and most Navajo children enter school knowing only English.

In the Rock Point school — one of the first reservation schools to be run by a locally elected school board — the Binghams taught English partly by having children interview elders and translate their stories. Even before he was in his teens, Janet Bingham recalls, Jim “could take what people said and translate it so that it sounded like poetry.” Jim interviewed his mother, who told the story of her great-grandmother’s kidnapping by Mexican slavers.

The stories that Jim and other Rock Point students collected were compiled into a book, Between Sacred Mountains. Anthropologist Robert C. Euler wrote in the Journal of Arizona History, “Of the hundreds of books written about the Navajo, this one is unique. It was written about the Navajo by the Navajo and for the Navajo.” A grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities enabled the Binghams to produce a second book, Navajo Farming, which documented tribal ties to the land. Although still in junior high school, Jim worked on both projects as an all-purpose consultant, editor, interviewer, translator, and photographer.

Just more than half of all Navajo children finish high school, and fewer than 5 percent complete college. To help Jim beat those statistics, Sam Bingham arranged for him to spend a year at the Newfound School, a small, experimental school in Asheville, N.C. Jim’s family staged a blessingway for him before he left on a flight — his first — for North Carolina. There, Jim lived with John and Anna Ager, the school’s directors, and helped them with farm work. Although he was an eager student, John Ager says, there were a few cultural clashes. Jim played on the Newfound School basketball team, for example, and before one game it was discovered that their opponents had brought almost identical green uniforms. Ager suggested that the schools instead play shirts and skins, which alarmed Jim because taking one’s shirt off in Navajo culture is a way to declare war.

“I think he thought this was a little higher level of competition than he had been expecting,” Ager says, laughing.

The Agers had strong Princeton connections: The school property was owned by Ager’s father-in-law, James McClure Clarke ’39, and Ager’s brother-in-law, William Clarke ’76, recently had graduated from the University. At the end of the school year, the Agers took Jim to their summer home in Lake Placid, N.Y., and stopped in Princeton along the way. Jim was captivated. “I said, ‘I’ll come to this school,’” Jim recalls. “But John said, ‘Oh, you have to be very smart to go there.’” So Jim returned West and finished high school at a private school in Carbondale, Colo., before beginning at Princeton.

More so than most freshmen, Jim arrived at Princeton alone. His parents, who had lived their entire lives in the Navajo world, “had no idea what Princeton was all about,” Jim says. At 20, he also was older than most of his classmates, with horizons much broader and yet much narrower than theirs.

He revived the dormant Native Americans at Princeton group, with himself as the only member. It was not the only way in which Jim felt himself set apart. Early during his freshman year, he was approached by an African-American student who invited him to join the Third World Center. Her suggestion that the two of them shared a common bond as Princeton outsiders offended him.

“I thought, ‘One, I don’t consider you Native American. You’re black,’” he remembers. “Two ... I’m fluent and literate in Navajo. I have access to a whole different body of literature and stories and ways of life, and you don’t have that.’ The conclusion was that, no, we don’t have anything in common.”

Instead, Jim spent most of his time with the international students, which fit his conception of himself as a citizen of a foreign nation and not a hyphenated American. He was particularly close to his two sophomore-year roommates, Marcos Rodriguez, of Puerto Rican descent, and Jeff Sedayao, a Filipino. Rodriguez recalls that Jim agreed to room with them in a three-room suite on the condition that he got the one single bedroom, and that he became notorious within New New Quad for his addiction to the arcade game Ms. Pacman. After his junior year, Jim spent the summer in Tokyo teaching English through Princeton in Asia. He developed a strong interest in Japanese culture, he says, because the Japanese have been able to embrace Western culture without losing their own.

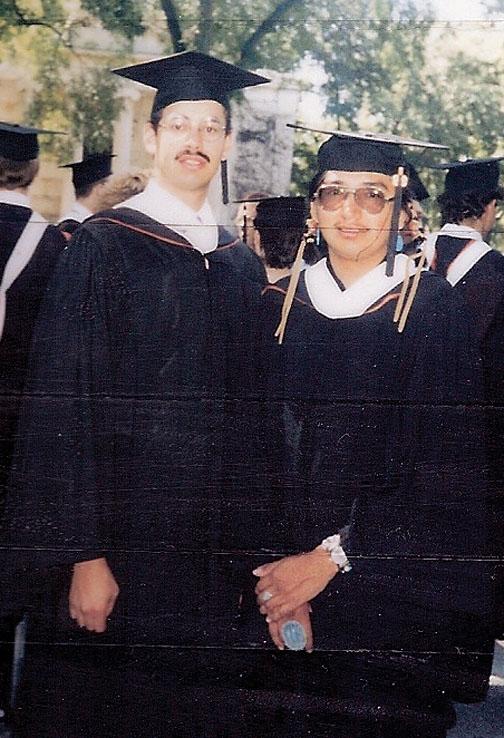

Academically, Jim’s adjustment to college was smooth. He banged out term papers late at night on a small manual typewriter. He majored in English, encountering a new world of literature, including Edmund Spenser’s epic Elizabethan poem, “The Fairie Queene,” which he still counts among his favorites. He also began working with Alfred Bush, reading and digesting Native American periodicals. Bush later helped publish two collections of Jim’s poetry, Ahi Ni’ Nikisheegiizh (1989) and Saad (1995).

It was during this time that Jim began to grow his hair long for the first time and wear Navajo jewelry. A quarter-century later, when asked why, he brushes off the question with a joke that cuts off the inquiry. “Who knows? Maybe I didn’t have enough money for a haircut?” His senior thesis, “Do Navajos Love as White People Do?,” examined the way white writers such as Zane Grey and Oliver LaFarge depicted Navajo concepts of love in their fiction. His thesis provides a window into his attempts to place himself between his own background and the non-native world.

“There is no doubt,” he wrote, “that white writers who write about Navajos will never achieve the level of thinking and feeling that Navajos have. Every time they try to deal with what makes a Navajo Navajo, they end up interpreting those qualities in their own terms. ... Instead of helping them out through their misinterpretations in the novels, these writers destroy the very people they try to help.”

No one outside Navajo culture, Jim concluded, could fully understand it, in large part because an outsider could not fully understand the language and the concepts it embraced. His thesis adviser, Thomas Roche, now the Murray Professor of English emeritus, recalls that when he would ask Jim to explain what non-Navajos got wrong in their depictions of Navajo tribal meetings, Jim would reply, “I cannot divulge sacred matters.”

“I knew,” Roche says, “I had gone as far as I could go.”

In the spring of 1986, Jim graduated with the intention of pursuing a master’s degree in English. He returned to Rock Point for the summer and, much as the Binghams had done 15 years earlier, learned that the school needed teachers and decided to stay. Over the years, he continued writing, publishing poetry in numerous magazines and anthologies in translations he calls “rough English.” One collection, Duchas-T’aa Koo Diné, published by the Irish Press in 1999, was translated into English and Gaelic. He received fellowships from the NEH and the Bread Loaf School of English at Middlebury College. He wrote the libretto for a Navajo opera he hopes to finish some day. And he eventually earned his master’s degree in English from Middlebury in 2001.

Jim also has remained involved in Navajo education, teaching creative writing, comparative religion, and a playwriting class in which students wrote and performed a play in Navajo. In 1995, Jim brought 10 of his Rock Point students to Princeton for a performance of traditional Navajo songs and dances. He serves on the faculty of Diné College, the Navajo college in Tsaile, Ariz., and from 1992 to 2002 directed its teacher-education program, training a new generation of Navajo teachers and developing curricula based on tribal language and culture.

“There’s an emphasis on Navajo that you teach who you are — and if you don’t know who you are, then how do you teach who you are?” he explained several years ago in an interview for the Native American Higher Education Initiative. Many of his students questioned the usefulness of their language. “I started writing and reading Navajo poems to them,” Jim continued, “and talking to them about all the places I traveled to, the Soviet Union, to China, to Japan, Vienna, different places, reading in Navajo, talking about the Navajo language. And then that inspires them. That says, ‘Yes, we can do something with this, we can move beyond the Navajo Nation, beyond the United States. We could travel worldwide using Navajo.’” Today Jim, who has never married, tries to pass those values along to his sister’s five children, three boys and two girls ranging in age from 11 to 23, for whom he is the legal guardian and who live with him and a younger brother outside of Rock Point.

Seeking to play a greater role in the Navajos’ future, Jim also entered politics. In 2002, he won a seat on the Navajo Nation Council and was re-elected four years later. He is especially proud of increasing the miles of paved roads within his district. Though he acknowledges the area’s poverty, he suggests keeping things in perspective: If one values clean air, breathtaking sunsets, wide-open spaces, and a lifestyle lived in harmony with ancient traditions, the Navajos are rich beyond counting.

In Jim’s capacity as a council delegate, he served as the Navajo Nation’s representative to the United Nations and participated in the drafting and passage of a Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples by the U.N. General Assembly in 2007. The Navajo Nation needs to start “thinking 50 years down the road, 500 years down the road,” he said at a subsequent meeting of the U.N.’s Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues. “How do we put ourselves in a position to help other indigenous people?” Work on these issues takes him to Geneva, New York City, and Washington, D.C., the latter as part of a group working on a similar declaration of rights for the Organization of American States. Last May, former President Jimmy Carter asked Jim to participate in a conference to improve relations between the United States and the five Andean countries of South America.

During his presidential primary campaign, Jim set up a campaign website and Facebook fan page, but there were no Rex Lee Jim billboards and only a few ads on the Navajo radio station, KTNN, each of which ended with the customary signoff — “I’m Rex Lee Jim, and I approved this message” — in Navajo. Jim relied on his personal ties to seemingly everyone in Navajoland and on face-to-face campaigning. “I believe voters like to meet their candidates,” he says.

In the general election, the Shelly/Jim team focused on infrastructure development and improved education. Win or lose, Jim says he plans to continue his international work, promoting awareness of Navajos and their issues. “The Navajo Nation needs to proclaim itself to be a sovereign nation, and we need to act like a sovereign nation, which means engaging in international lawmaking,” he insists. “When people talk about the right to self-determination, a lot of indigenous people think it means only the right to vote in national elections. But for the Navajo Nation, the right to self-determination includes self-government.”

Both the poet and the politician in Rex Lee Jim say that this starts with strengthening the Navajo identity and preserving Navajo heritage — and those goals begin with their language. He would like to see Diné College become a four-year institution and also offer graduate education. He deliberately has not translated most of his works into English because he believes that doing so saps them of their potency — and also because it would undermine efforts to encourage younger people to learn the language. He speaks Navajo whenever he can and says he uses the language to heal himself and overcome obstacles. By lifting his people’s pride in themselves, he believes, the Navajo language can prevent alcoholism and many other social problems.

“The gods,” Jim has said, “have already given you the Navajo language. All you have to do is tap into it.”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.