Richard Morse ’79 stands at the bar of the Hotel Oloffson in downtown Port-au-Prince, elbow resting on the counter, chatting with a guest who sips the hotel’s trademark rum punch. It’s a typical spot to find Morse, manager of Haiti’s most famous hotel, on a weekday evening. But tonight his usual detached cool is ruffled.

His wife, Lunise, is still getting ready. The bus with the other band members left for the concert in remote southwestern Haiti hours ago, while it still was daylight. Now Morse will have to drive in the dark. But years of marriage and playing music together have taught Morse one thing about his lead singer and principal talent: Lunise can’t be rushed.

Morse asks for a glass of water. He is a portrait of marital and managerial despair. Not exactly what you’d expect from the leader of one of Haiti’s best-known bands. The two near-identical portraits of Haitian revolutionary hero Jean-Jacques Dessalines that bracket the bar seem bemused.

By day Morse runs one of the handful of hotels in Haiti’s capital left standing after January’s earthquake. By night he crisscrosses the island in an SUV to play his signature Creole spirituals set to rock music. He’s got four gigs this week, another four next. It’s Haiti’s summer festival season, and while the drives are long and the weather is oppressive, he accepts every offer he can.

It’s been this way since the earthquake. Song and dance, so much a part of the cultural life in a nation where half the people can’t read or write, were all but absent from Haiti in the aftermath of the quake. The 53-year-old Morse helped to bring it back. He was among the first musicians to hold a concert — three months after the quake, on the hotel’s front lawn, free for all. Thousands came to sing and cry. It was as if the island itself shuddered in pain and ecstasy, in profound release. Since then, Morse’s band has toured tent camps playing free concerts.

After an hour, Lunise emerges, wearing a striking yellow dress and head scarf. Morse straightens from the bar. He calls for his 19-year-old son, William — named after Richard’s grandfather, Princeton Class of 1902, football player, president of Cottage Club — and says it’s time to go. The five of us — Morse, Lunise, Will, a photographer, and I — walk down the main staircase, past the statue of Baron Samedi, a Vodou lwa — or deity — of the dead, and pile into a Toyota Land Cruiser for the four-hour journey to the concert venue, a remote village called Saint-Louis-du-Sud.

With the collapse of the presidential palace and the Notre Dame Cathedral, the 115-year-old Hotel Oloffson — owned by the powerful Sam family, which boasts two former Haitian presidents — is perhaps the most famous building left standing in Port-au-Prince. The gingerbread mansion teeters on a hillside overlooking downtown, its tree-lined circular driveway an oasis of tranquility in a city of dust and dirt. It is in a state of decades-long decay, “supported on the back of its termites,” novelist and frequent guest Herbert Gold wrote in The Hudson Review. An interior staircase slants perilously; the walls are cracked and frayed. Gold says that the way you know something is broken in the Oloffson is when it falls down.

That this hotel, of all places, withstood an earthquake that flattened the city and killed an estimated quarter-million people is both remarkable and, somehow, fitting. It’s a magical place. Graham Greene best captured that magic in his novel The Comedians: “With its towers and balconies and wooden fretwork decorations it had the air at night of a Charles Addams house in a number of The New Yorker. You expected a witch to open the door to you or a maniac butler, with a bat dangling from the chandelier behind him.” Little has changed in the nearly half-century since that was written, or the quarter-century Morse has managed the hotel, except perhaps the witches have been replaced by lwa.

“I don’t even know how I got into the hotel business,” Morse says. His first love always has been music. Twenty-five years ago he came to Haiti with a vague plan to learn his mother’s folk music and adapt it to modern ears. Back then he imagined himself as an international rock star. Now he prefers to play his music for Haitians. “I came to Haiti for the rhythms,” he says, “and I learned the rhythms don’t walk alone.”

Post-apocalyptic Port-au-Prince is filled with piles of the concrete remains of buildings. Yet during the day, hundreds of people swarm the streets. They’re part of massive open-air markets that are the only economy left downtown. Vendors hawk bruised cabbages, handicrafts, and donated goods. Cardboard containers tossed into fetid canals are lit on fire. People cram aboard brightly colored Tap Taps, jitneys that take them back and forth to the tent camps they now call home. Death is taken for granted. One evening at dusk, my driver swerved to avoid the body of a young man freshly shot in the head, lying in a pool of cherry-red blood.

Tonight, as we drive through downtown toward the concert, the city streets are pitch-black. There are almost no street lamps or electricity of any kind — just flames from kerosene lamps and burning trash. The city’s permanent sheen of dust diffuses the opposing headlights. It feels like we’re driving into a cave.

We drive southwest, toward one of two narrow peninsulas that extend from the mainland like pincers on a beetle. “We’re headed toward the epicenter of the earthquake,” Morse says. Fissures scar the two-lane road headed out of the city. Pockmarked pavement suddenly gives way to gravel, then just as jarringly is paved again. I say it feels like we are driving on the surface of the moon. Morse laughs.

This is the main road in southwest Haiti, one of the poorest parts of this poor country. The alternate paths are by foot or by donkey. It is unclear whether the patches of gravel in the road are from decay, natural disaster, or corruption.

We have the radio on, and it plays the latest song by hip-hop star Wyclef Jean. Jean’s brief run for Haitian president was cut short when the nation’s electoral council ruled him ineligible because he hadn’t lived in Haiti for five consecutive years prior to the election. Jean wrote a protest song that had become a runaway hit among his many fans. In the song, the Haitian-born Jean addressed the criticism that he was a blan, a word that literally means white but is used in Haiti to mean non-Haitian, by singing in poor Creole, the country’s indigenous tongue. Morse listens intently. Though Morse writes his songs in Creole, he sings with an American accent. Suddenly, Morse bursts into laughter. “Wyclef sang douce makoos instead of douce makoss,” he says. “He’s just memorizing the lines. He really can’t speak Creole.”

“That was the worst song ever,” his son Will cracks from the back. “I bet Wyclef wrote it on the plane back to the U.S.”

We are now in the countryside. We drive past broken-down trucks, past rows of banana trees, past the inky darkness of the sea, past peasants walking their cows like pets, past fishing villages where the main street is marked by a single oil lamp, past dozens of tent villages. We drive past a sign that reads in English, “We need help.”

Richard Auguste Morse was born into WASP privilege. His father, Richard M. Morse ’43, was a history professor and the head of Latin American studies at Yale. He sent his son to elite boarding schools, and the son fulfilled his destiny to become a third-generation Princeton man. “I can trace my father’s side of the family back to Massachusetts in 1635. Puritans,” he says. “My ancestors would have hunted me down and stoned me and my mom.”

Emerante de Pradines was a Haitian dancer and singer known widely as the most beautiful woman in Port-au-Prince. She was the first person to sing Vodou songs in Creole on the radio even as the government was trying to stamp out the Afro-American folk religion. She met her husband at a dinner party, and they married at a time when mixed-race couples were not seen on Ivy League campuses. “It was a scandal,” she says. They spent 17 years in New Haven. Emerante taught in the drama school and became a cherished figure on campus.

Today, Emerante is 92 years old and a widow. She runs a school for poor Haitian children on a hillside outside the capital. “Richard was born in a law country,” she says of the United States. “I was born in a free country.” Haiti was the world’s first republic ruled by former slaves. “Richard has a good heart, but sometimes he can be a little confused about his birth.”

As an undergrad at Princeton, Morse and some Princeton classmates started a band called the Groceries. Their first paid gig was at Terrace Club, for $400. They graduated to the underground rock scene in New York, one more startup band trying to make it big. But Morse was restless.

During that time, Morse visited Haiti with his mother. Emerante remembers watching her 22-year-old son walk up three flights of stairs to the upper balcony of her family’s multi-tiered home outside Port-au-Prince where she still lives. Morse turned to face the verdant valley, opened his arms wide, and yelled, “Ah, this is my country!”

Soon afterward, Morse quit the Groceries, or he was kicked out, or some combination of the two, and he moved to Haiti in 1985. As a day job he took over the lease at the historic Oloffson. It was big news on the island, and even got written up in The New York Times.

This first part of Morse’s journey follows an arc similar to that of “Mr. Brown,” the expat hotelier and narrator of The Comedians. In the novel, Mr. Brown inherits the “Trianon” hotel from his mom, feels an unlikely and powerful connection to the place and the people, and makes the hotel his home. But things get hairy, as they always seem to do in Haiti, and Mr. Brown is forced to move abroad. He becomes a mortician in the Dominican Republic.

Morse veered from the second part of that script. The politics in Haiti got hairy, but Morse stayed. He married Lunise, a Haitian singer and dancer. He founded the band RAM, taking the name from his initials as well as from the name of the animal, important in Vodou ritual. He set Afro-Caribbean folk rhythms to rock instrumentation in a formula that became known as “Vodou rock.” He took RAM on several European tours, briefly tasting the life of an international rock star he had imagined for himself.

When I first ask Morse about his connection to Vodou, he doesn’t want to talk about it. But on my last afternoon at the Oloffson, he relents.

“Want to see my room?” he asks. His dog (named Tiger Woods) and I follow him down the snaking stairs of the hotel compound, past the pool, to an annex where I’d been staying. “Tiger Woods loves Vodou,” he laughs. He fishes for his keys and opens a padlocked door.

Vodou is the religion slaves brought to the New World, a melding of West African practices with Judeo-Christian beliefs. Vodou has a supreme god and creator. Believers also worship lesser spirits, the lwa, each of which is associated with a Christian saint. Vodou and music are intimately tied. That is what Morse meant when he said Haitian rhythms “don’t walk alone.”

Inside the room, tables are filled with relics: holy water, gourds, a machete, cigar butts, bottles of rum and champagne. Each table seems dedicated to a lwa. There is a framed portrait of Dessalines. On the bed is a guitar. Morse says this is where he writes many of his songs.

He slides off his shoes and goes into a closet, emerging with a candle lit from a flame he says is never extinguished. He sits on the floor, pours olive oil into a small container, fashions a floating wick using four corks and a twisted cotton, and lights the wick with the candle. It flickers on our faces in the darkened room.

“In a dream, someone gave me these words that at first I didn’t understand: Follow your mother,” Morse says. That was nine years ago. “Vodou is part of my inheritance,” he says. “It just took me a while to get there.”

Richard, the son of an atheist father, went through an initiation in Jacmel to become a Vodou priest. His mother was there for the four-day ceremony. I ask him what it was like. Difficult, he says. “I had a lot of non-belief in my blood I had to get through.” After it was over, his mother embraced him. She told him, “I didn’t think it would take you this long.”

Thursday nights at the Oloffson are RAM nights. In a country wracked by coups and corruption, violence and poverty, RAM Thursdays are about the only sure thing.

When Morse established the Thursday-night show in the early 1990s, some fans complained. They had to work the next day. Morse persisted. “I did it because Thursday was pub night at Princeton,” he says.

One sweltering Thursday evening in August, the lobby and veranda fill with a mix of locals, aid workers, and a smattering of tourists. White and black mix easily. A bouncer collects guns at the door — a practice that began in response to threats against the band from military authorities.

Morse is preparing in a back room. As on most Thursdays, tonight he will wear the top hat of the lwa Baron Samedi. The bar manager arrives to tell him that they have run out of Rhum Barbancourt, Haiti’s best-known rum. And not just the bar, the manager explains — the entire country. This sort of thing is part of running a hotel in Haiti. During the earthquake, Morse and his family scoured the island to find food for the hotel guests camped in his driveway. Now he makes a call and a stash of rum is on its way.

RAM plays two sets. The first set is for the foreigners. The band has conga drummers, electric guitar, and horns. At times they sound like a New Orleans brass band. About 150 people gyrate in the humid hotel lobby.

The second set starts at 1 a.m. The scene has shifted. The white faces are gone. The music gets more intense, more intimate, more ceremonial. The crowd thickens into an intense personal closeness. People move as a single mass. The hallway lights flicker on and off with periodic brownouts that are endemic in the capital, but the sound system is on a generator, and the music continues uninterrupted.

Morse, who sings and leads the band, dances stiffly. His top hat bobs above the crowd like a toy boat. He purses his lips and peers through his glasses, scanning the crowd and his band members with a satisfied look.

A mass of young men springs amoeba-like onto a square of open dance floor in front of the bar. The men are lithe and feminine as they leap up and down and mosh and grind and fall into each other. Homosexuals are outcasts in Haiti, and the Oloffson is known as the only place where a man can be openly gay. The young men finish showing off, sweaty and laughing, and rejoin the fray to applause.

At 3 a.m., Morse leads the band in a conga line through the crowd. People dance through the lobby, past the bar, onto the porch, and finally off stage right. Morse poses for a photo before disappearing into a back room. The crowd disperses quickly. Tables are covered in empty bottles of Prestige beer wrapped in white napkins.

On our journey to Saint-Louis-du-Sud, an hour past Jacmel, we are stopped at a police roadblock. This is where driver’s licenses are checked — and small bribes are often collected. Morse says he never carries his license, that he doesn’t need it. As a police officer approaches, Morse turns on the interior light of the SUV. The officer immediately recognizes the leader of RAM and, after a fawning chat, waves him through. “You know, Dad,” Will says, “you should really drive with your license. It’s the law.” Morse glances back at his son. “Why?” Morse says later that’s one of the perks of being a rock star in Haiti.

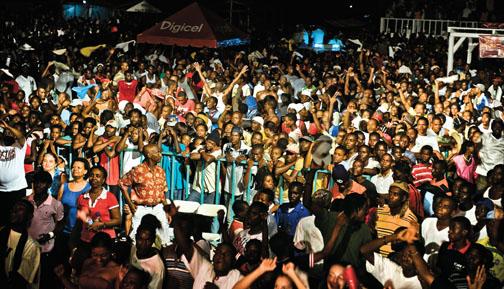

It’s past 11 p.m. when we arrive at the venue in Saint-Louis-du-Sud. Tonight’s concert is the headline event of the town’s annual Saints Day festival. It’s sponsored by the local government, and it’s the social event of the year for all the neighboring villages. It has drawn a crowd of 15,000. “We’re a long way from Nassau Street,” Morse tells me.

He skips the parking lot and directs the SUV toward the stage. We drive through a pedestrian area clogged with cardboard roulette tables with handmade wheels and food stands with hot dogs and pork and conch and chicken cooked by gaslight. As we inch along, vendors pick up their tables and pedestrians part. This is a poor part of the country, and people make way for anyone in a car.

A man on a motorcycle refuses to move. He sits on the tail of the bike, elbow resting on his knee, and stares into our headlights. His eyes are red. He keeps staring. Morse waits. Finally, the man slides off the seat and slowly walks the motorcycle into the darkness. “In a poor town, he’s a man with an income, probably from abroad,” Morse says. “He wanted to prove that he’s a big man. But I’m the one in the car.”

The crowd consists of rural farmers and their kids. “Before, you were in the Republic of Port-au-Prince,” Morse says. “Now you are in Haiti. The music we play is their music. And it puts me in touch with them. To the elites I’m a traitor, politically and socially.”

Morse is part of a musical movement in Haiti called mizik rasin, or roots music. Rasin bands incorporate the drum rhythms of traditional and ceremonial music with melodies from rock and pop. Most of the words in Morse’s songs are drawn from Haitian parables or Vodou prayer. Some, such as “Boat People Blues” and “The Visa Song,” are drawn from current events. The lyrics are often elliptical but politically suggestive. “The country is not in a good state,” he sings in a song ostensibly about the weather. “When I try and go up above, I get the crack of the whip. When I try and go below, I get a bottle of bad juju.”

To be a musician in Haiti, and in particular to sing folk music in Haiti, is a radical political move. It has long been so: Morse inherited his mission from his grandfather, the well-known troubador Auguste de Pradines, whose 1920 song “Angelique O!” describes a domestic squabble but also was interpreted by the masses as a call for an end to the U.S. occupation of Haiti. “When we were in the Groceries, Ronald Reagan didn’t stop to find out what we were singing about,” Morse says. “Ronald Reagan didn’t care, the police didn’t care, the CIA didn’t care, the military didn’t care. In Haiti, all of their equivalents care what we sing about.”

Morse almost always has stood in opposition to the 21 governments that have ruled the island since he arrived. He was an early supporter of President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, but he soured quickly as the Aristide government turned violent. He has been threatened repeatedly and told to leave the country. His songs have been banned from the radio. Armed thugs have disrupted his concerts. And yet, while generations of musicians have been forced out of the country by their blunt lyrics, Morse has managed to stay.

Novelist and journalist Bob Shacochis, in his book The Immaculate Invasion about the 1994 U.S. intervention in Haiti, writes about an assassination attempt on Morse. It was Carnival of 1998, and René Préval was the president. Morse had clashed with the mayor of Port-au-Prince, another political musician named Manno Charlemagne. RAM was playing on a float decorated with angels.

Shacochis writes that the assassination attempt began when the driver of the float, which had been inching along for six hours, suddenly stepped on the gas and careened into the crowd: “‘Stop the float!’ Lunise screamed into the microphone to no avail. ‘Stop the float!’ Gerrard Laforrest, the chief of RAM’s security team, was the first person killed. The driver plowed onward through waves of celebrants, jumped the curb in an attempt to tip the float, then smashed into a tree. Equipment and people on the float were pitched into the air; a drummer broke both legs. The band’s generator burst into flames; people trying to put out the fire were beaten by unknown assailants. Then the silence descended, disrupted only by sirens and the cries of the injured — dozens of victims, and eight people dead ... Hidden inside the wreckage by their friends, Morse and Lunise hopped to the ground, running for their lives through back alleys of Port-au-Prince until they were finally safe, for the moment, inside the Oloffson.”

Wyclef Jean and Manno Charlemagne now live in the United States. Other Haitian musicians have been killed. Yet Morse, through a combination of luck and will, continues to speak out and play music in Haiti. “Everyone thinks I can speak out because I’m an American,” Morse says. He isn’t sure he disagrees.

“With my music, I’m providing a safe haven for folks as the government fails,” he says. “There are times when the Haitian people can’t speak out. But I can write a song.”

Since the earthquake, Morse has found a following beyond his music. His Twitter account, RAMHaiti, has 14,600 followers. His acutely observed dispatches were among the first bits of information to flow out of Haiti after the earthquake. “I’m trying to find a positive point of view, and all I can come up with is: A lot of people didn’t die,” he wrote a day after the quake. Some of his tweets have the sound of a song: “Will Haiti start anew? That’s the question of the day. What’s the direction? Same direction as last year? No one seemed to like that path.”

As the 16 members of RAM take the stage in Saint-Louis-du-Sud, the atmosphere is electric. Their second song is “Madame Letan,” which translates to “Mrs. The Weather.” Morse wrote it in 1998, when four hurricanes came through town: “Hello Madame Letan, what have you done to me? You took my mother, you took my father, you took my pig, you took my goat, you took my cow, you even took my false teeth. What’s there left for me in this country?” That was before the earthquake.

Morse says the lyrics of this song, as with many of his songs, are based on a traditional Creole prayer.

After the assassination attempt, Morse lowered RAM’s profile in Haiti. “We were too popular,” he says, “and it was messing with the government.” The band did three European tours and skipped out on Carnival for a decade. Then, in 2008, Morse was persuaded to write another Carnival song. He wrote about Jean-Jacques Dessalines, a leader of the Haitian revolution who named himself emperor until his assassination in 1806. The former Vodou priest is adored among the Haitian people for his fighting spirit, and every October there’s a national holiday to commemorate his death. The RAM song became an instant hit.

“We celebrate the death of Dessalines, but we don’t celebrate his life,” Morse sings in the final song of the concert. “Father Dessalines, you will always be our general, you will always be a great emperor.”

Morse puts down the microphone and turns to the crowd. Everyone is dancing and waving white towels and singing along. He is where he always wanted to be. On stage. A rock star. With his people. He opens his arms wide, takes it all in. He is back on that balcony with his mother. He has found his country.

Dan Grech is the radio news director of the WLRN Miami Herald News, a daily newscast produced jointly by The Miami Herald and public-radio station WLRN.