If Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels ’71 decides to seek the Republican presidential nomination next year — and he remains coy about his intentions — he would have to win over crowds like the one that packed the ballroom of the American Conservative Union in February for the Conservative Political Action Conference.

Daniels, some pundits suggested, had conservative fences to mend because of remarks he made to The Weekly Standard — that the gravity of the country’s fiscal problems make it necessary for the left and right to “call a truce” on divisive social issues such as gay marriage and abortion. But if Daniels did not sound as angry as other CPAC speakers, he still managed to excite the activists by throwing out a different topic.

The federal budget deficit, he said, confronts us with “the new red menace, this time consisting of ink,” and “an enemy, lethal to liberty, and even more implacable than those America has defeated before.” Moreover, he said, it is the “generational assignment” of baby boomers like himself to do something about it. “No enterprise,” Daniels declared, “small or large, public or private, can remain self-governing, let alone successful, so deeply in hock to others as we are about to be.”

Dire as the federal fiscal outlook is, the situation in many states is worse. And Daniels has drawn national interest because of the record he has amassed in Indiana. Over the last six years, he has transformed a big budget deficit into a large surplus, created a public-private alliance to spur economic development, and privatized some state services while still allowing for the occasional tax hike. New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie gets a lot of the press as a fiscal reformer, but Daniels, who was elected governor in 2004 and re-elected handily four years later, has a longer track record, one that led Governing magazine to include him among its Public Officials of the Year in 2008. Newsweek’s Andrew Romano ’04, who spent several days with Daniels last summer, characterizes him as “about as parsimonious as you can be as an actual working politician.”

Devotees of Ayn Rand-style, laissez-faire capitalism will be disappointed by Daniels. “Government should be limited but active, and its activity ought to be directed at enabling the private sector to flourish,” he tells PAW. “Skepticism about big government is very healthy and very American. But we will never let skepticism about big government mutate into contempt for all government. I think that some people, maybe thoughtlessly, let that happen.” He adds that he believes in “a carefully defined sphere for public activity,” and within that sphere, “we are duty-bound to demonstrate effectiveness and spend every dollar very wisely.” As governor, he has been trying to translate that philosophy into changes that taxpayers can see.

Daniels is a man who believes in measuring things, which led him to create a state version of the federal Office of Management and Budget, which he directed for two years under President George W. Bush. To improve service at Indiana’s Bureau of Motor Vehicles, he insisted that customers’ receipts be stamped with the time they entered and the time they were served; customer wait times have dropped from 40 minutes to less than 10 minutes. Indiana had straddled the Eastern and Central time zones; to increase efficiency, Daniels moved most of the state to the Eastern Zone. Because prison costs take up an increasingly large share of the state’s budget, Daniels has pushed for more flexibility in sentencing, particularly for nonviolent offenders. He even directed the Indiana revenue department to save the paper clips on citizens’ tax forms so the office could reuse them. “He’s a little gutsier than your typical accountant,” says Larry DeBoer, a professor of agricultural economics at Purdue University. “He comes across as more of a policy wonk than many political leaders do.”

It is not easy to pigeonhole Daniels ideologically. He has expanded the availability of all-day kindergarten, though he fell short of a campaign pledge for universal access. He transferred responsibility for child-welfare programs away from localities and to the state, greatly increasing the total number of caseworkers. Recent job reports show a decline in Indiana’s unemployment rate, though it remains above the national average, and the state has landed three new auto plants.

It would be a mistake, however, to view Daniels as a mushy centrist. One of his first steps in office was to break the power of state public-employee unions. While another Midwestern Republican governor, Scott Walker of Wisconsin, caused a firestorm in February by moving to strip state employee unions of collective-bargaining rights, Daniels did the same thing, to much less fanfare, on his second day in office and since has defended it as “absolutely central to our turnaround.”

Elimination of collective bargaining gave Daniels greater freedom to consolidate services, cut the number of state employees (Indiana now has the fewest state employees per capita in the nation) and outsource printing, computer purchases, and prison food services. Not all privatization efforts succeeded, including a plan to outsource the state’s welfare enrollment program, and one project — leasing the Indiana Toll Road to a private consortium — was particularly controversial, though it has increased revenues and seems to have grown in acceptance since the 75-year lease began in 2006. The policies have driven down membership in Indiana’s state employee union by 90 percent, and Jeff Harris, a spokesman for the Indiana AFL-CIO, says that the governor “has seemed to put the profits of corporations ahead of the livelihood of ordinary Hoosiers.”

However, when Democrats in the state General Assembly left the state in late February in an attempt to thwart Republican efforts to make Indiana a right-to-work state, Daniels urged Republicans to back down. Although he supported such legislation in principle, he said, pursuing it now would sidetrack important measures that would require Democratic votes. Those remarks drew Daniels an editorial rebuke from The Wall Street Journal.

Although Daniels has a traditional conservative’s dislike of taxes, he has at times proposed raising them. When local school districts attempted to raise taxes to replace cuts in state funding, Daniels had the state education department post a Citizen’s Checklist online that residents could use to question their school boards about whether they had really made all possible economies. On the other hand, in his first state budget, Daniels proposed raising several taxes and fought the state House speaker from his own party to get some of them passed.

In 2008, Daniels pushed legislation that capped property taxes — caps that since have been incorporated into the state constitution. Lost revenues were offset partially by an increase in the more regressive state sales tax — but DeBoer, at Purdue, notes that sales-tax receipts dropped sharply as the recession progressed. That has meant teacher layoffs and significant cuts in other services. Daniels points out that the property-tax caps can be raised by local referendum, and that more than a third of such referenda have passed. “What it says to me,” he reasons, “is that if government can make a good case [for tax increases], at least in our state, citizens will go along with it.”

Brian Howey, who writes a daily online briefing on Indiana politics, says it will be impossible to know the results of Daniels’ budget cuts for the next five or 10 years. But he gives the governor points for eliminating the “smoke and mirrors and tomfoolery” that’s usually a part of the budgeting process.

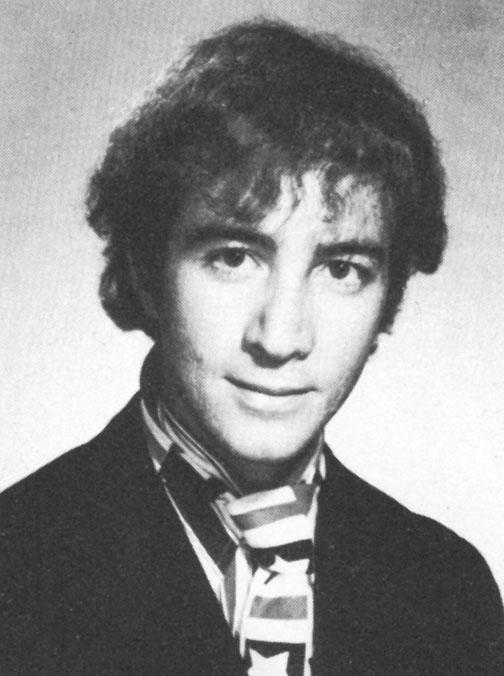

Although he grew wealthy as senior vice president at the Indianapolis-based pharmaceutical giant, Eli Lilly & Co., Daniels has spent much of his career in the public sector. As a Princeton undergraduate, he served on the steering committee of the Union for National Draft Opposition and the Orange Key Vietnam Moratorium Committee. He describes those years as a time of “experimenting, sampling,” and indeed, in 1970, Daniels was arrested for possession of marijuana and LSD, spent two nights in jail, and paid a $350 fine on a reduced charge of maintaining a common nuisance. (Years later, in an article for The Washington Post, he dismissed the experience as “an unfortunate confluence of my wild-oats period and America’s libertine apogee.”) In his senior year at the Woodrow Wilson School, Daniels said in the Nassau Herald that his plans were to cruise the Caribbean and then “be a political consultant to acceptable candidates.”

He found his acceptable candidate in Republican Sen. Richard Lugar, who was then mayor of Indianapolis and known as “Richard Nixon’s favorite mayor” for his staunch conservatism. Daniels worked for Lugar and moved with him to Washington, earning a law degree from Georgetown at night, until he joined the Republican Senatorial Campaign Committee in 1983. In 1985, he joined the Reagan White House as a chief political adviser, and left two years later to head the Hudson Institute, a conservative think tank. In 1990, Daniels entered the private sector to become an executive for Eli Lilly (he eventually was vice president for corporate strategy and policy), leaving in 2001 to direct the OMB for two years.

As OMB director, Daniels is said to have tried to get the Rolling Stones’ song “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” to serenade callers on hold, but settled for having it played over the public-address system at the Government Printing Office when congressional staff collected their copies of the budget. Bush, a famous bestower of nicknames, dubbed him “The Blade” — though Daniels also worked on the $1.35 trillion Bush tax cuts and the Medicare Part D prescription-drug benefit, which helped turn a large budget surplus when he entered the job into an even larger deficit when he left it. Daniels also has been criticized for vastly underestimating the cost of the Iraq war in official projections.

He has tried to explain his OMB record by citing the government’s need to respond to a recession and the 9/11 attacks, but also suggests that he was just following orders. “[D]on’t look at two and a half years when I was in the supporting cast with no vote,” he emphasized on Fox News. “Look at six years [as governor], where I was in a responsible position, submitting budgets and fighting for them.”

Daniels has some thoughts on the national fiscal problems that, like his truce remark, might get him into trouble with some segments of the Republican primary electorate. “Let’s not approach this ideologically,” he says of the current budget debate. “Let’s have the philosophical debate tomorrow. For today, can we agree that the arithmetic does not work? So, the question is, what will produce the necessary revenues over time?”

To produce those revenues, Daniels has said he is willing to consider instituting a value-added tax, increasing gasoline taxes, and cutting defense spending. He favors raising the retirement age for Social Security and ending benefits altogether for the wealthy. “There is absolutely no reason,” he says, “that today’s young people should send me a pension check.”

As for Medicare, he has spoken favorably about both means-testing and eliminating the program altogether in favor of a voucher system. He has seemed sympathetic to rationing health care: “We all want to live forever,” he told a group of health-care reporters earlier this year. “We cannot afford — no one can — to do absolutely everything that modern technology makes possible to absolutely the very last day of the very last resort.” (Daniels also said, however, that decisions about when to end treatment should be made by a patient’s family.) He is sharply critical of the Obama health-reform legislation, saying it creates a costly new entitlement; he points instead to the health-savings accounts for the working poor that he has instituted in Indiana, which have broadened coverage — though not as much as predicted — and been paid for partly by raising the cigarette tax.

Daniels has disparaged cap-and-trade legislation and expressed skepticism about the validity of climate-change science. Mostly, he tries to steer the discussion into finance. “I don’t know if the CO2 zealots are right,” he told the The Weekly Standard. “But I don’t care, because we can’t afford to do what [environmental activists] want to do.” He has supported alternative-energy production, clean-coal technology, and conservation, however.

“Daniels actually is willing to talk about the elephants in the room,” writes Newsweek’s Romano in an e-mail, “reforming entitlement programs, slashing defense spending, and raising taxes if necessary.”

The governor is not noted as a fiery speaker; most reviews of Daniels focus on his height (5 feet 7 inches) and hair (receding). But in almost every presidential election, Jonathan Martin observed in Politico, one putative candidate wins plaudits in the press for his ideas and willingness to speak honestly. This year, Martin said, Daniels is the “heartthrob of the elites.” Indeed, reviews of his CPAC speech were laudatory.

Time

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.