A yearlong study has documented that undergraduate women at Princeton are underrepresented in the most visible leadership positions and as recipients of major academic prizes — disparities that have existed for the past decade.

“By and large, women feel that they are not expected or encouraged to fill certain types of leadership positions — but not that they are not entitled to fill them,” the Steering Committee on Undergraduate Women’s Leadership wrote in a 100-page report released March 21. “Women find many doors closed at Princeton, but few that are actually locked.”

The study group, announced by President Tilghman in the fall of 2009 — the 40th anniversary of coeducation at Princeton — was charged with exploring how students define and experience leadership and “the critical question of whether women undergraduates are realizing their academic potential and seeking opportunities for leadership at the same rate and in the same manner as their male colleagues.”

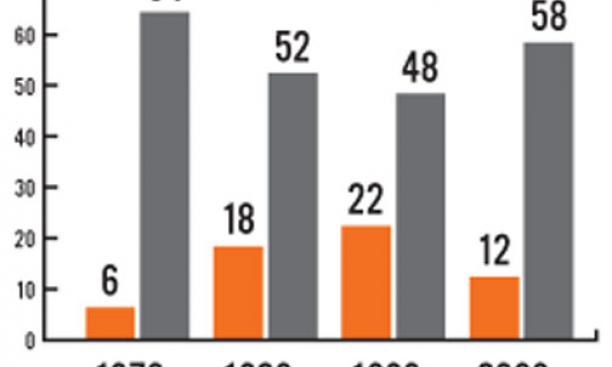

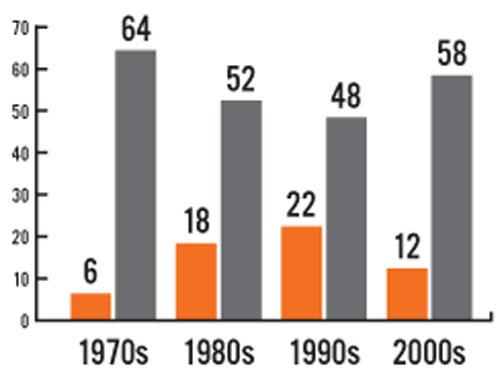

The committee found an “upward trajectory” in the number of women leading key campus organizations (student government, the Honor Committee, The Daily Princetonian, class president) as women’s enrollment increased during the 1970s through the 1990s. But it found a “striking” downturn in the numbers during the 2000s.

This pattern was mirrored in the gender balance of recipients of the Pyne Prize, the highest general honor for an undergraduate. Women outnumbered men who received the award in the 1990s — even though there were fewer women than men in the student body — but won only a third of the prizes in the 2000s.

The report also found that while women in general have higher grade-point averages and receive more honors and high honors, men dominate “the very highest levels” of academic achievement — including election to Phi Beta Kappa, University honors and prizes, and Rhodes and Marshall scholarships. (Men also dominate the lowest levels.)

The committee said it found similar gender imbalances among elective student positions at peer schools, but on the issue of the highest academic honors, Princeton’s experience stood out: “At many (though not all) of our peer institutions, women are outstripping men at this level.”

Differences between men and women are evident as students arrive as freshmen and begin to experience Princeton differently, the report said. While men and women bring similar academic credentials, women are less intellectually confident and less inclined to think of themselves as leaders, the report said.

The committee said that women are deeply involved in a range of campus activities, often in those perceived as “high-impact” as opposed to “high-profile,” and that “the essential work of keeping an organization on track ... is often done by women.”

Women who attended Princeton in the early years of coeducation “regarded themselves as pioneers and demonstrated notable courage and self-confidence,” the report said. But the committee found that women students today “tend not to invite the vulnerability associated with running for office or pursuing a leadership role unless they are explicitly encouraged to do so.”

Men, on the other hand, “are more likely to consider themselves plausible candidates for office or prizes and step forward without special encouragement,” the report said. The contrast also shows up in precepts and seminars, the report noted, where men tend to speak up more quickly, while women appear more hesitant to speak.

Committee members said that such traits are reflections of societal norms, though they may be intensified by aspects of the campus environment.

Some key changes noted by the committee were taking place as Princeton was being led by its first woman president (Tilghman took office in June 2001) and women held a number of top administrative and academic posts.

“The degree to which the institutional culture discourages women’s leadership stands in peculiar tension with the current reality of significant women’s leadership in the senior administration,” the report said. One alumna told committee members that while female students admire senior University leaders who are women, they “become ‘The Man’ and are not seen as women, only as leaders.”

The report offered recommendations to provide “parity of opportunities” for men and women, adding that most of the ideas would benefit all students.

MENTORING: Responding to a theme heard consistently from alumnae, the committee recommended strengthening faculty mentoring, encouraging upperclass women to mentor younger women students, and involve more graduate students and alumnae.

LEADERSHIP TRAINING: The committee suggested a “broad-based effort,” using existing campus programs and initiatives at other institutions as models and holding events that would encourage women to run for office.

ORIENTATION: The report called for a revamping of freshman orientation, citing the importance of a student’s first 100 days at Princeton in making choices about activities, willingness to step forward as a leader, and forming social networks.

FACULTY INITIATIVES: To prevent unintentional bias, the committee suggested tools such as “blind grading” (evaluating exams or papers without the student’s name attached) and the “five-second rule” (giving more students a chance to speak by waiting before calling on students in class), as well as encouraging exceptional students to apply for prestigious fellowships or graduate school.

MONITORING/RESEARCH: The committee called for more research on the experiences of Princeton students before they enroll and after they graduate, and suggested a progress report in 2019.

Tilghman said in an interview that the task for her administration will be to develop specific plans from the committee’s broad recommendations.

Preparing men and women to be leaders is one of the University’s most important missions, she said. “It’s the only way you can justify the enormous investment that this University makes in each and every one of its graduates: You have to believe they will go out and have a real impact,” she said, adding that leadership can be shown in many different ways.

Tilghman pointed to the report’s finding that social and academic life are intertwined at Princeton, and said that what happens in social settings has a profound effect on what happens in class. She said she believes that women are allowed a narrower range of acceptable behavior “in all spheres of life,” and if that is the case, it would not be surprising that in the classroom, women would have “inhibitions about either doing too well or too poorly — they want to be in the middle.”

She said that the University should celebrate all types of campus leadership, but that some positions “can have a more impactful effect on your life after graduation than others — that’s the way the world works.”

The study group was led by Professor Nannerl Keohane, former president of Duke and Wellesley. It included faculty, students, and administrators; 15 of its 18 members were women.