When writing a book about the BP oil spill — a highly technical subject he researched at hyperspeed — Washington Post writer Joel Achenbach ’82 relied on a simple rule: Never pretend to know more than you did.

The first obstacle facing Achenbach as he reported on the disaster was simply understanding the opaque and insular language of engineers and other oil-industry workers. When he attended his first investigative hearing after the spill, he found the rig workers’ language and vocabulary “completely foreign. I thought, ‘What on earth are they talking about?’ ” So he taught himself a passable fluency in engineer-speak by borrowing the most technical books about petroleum engineering he could find and poring over them every morning.

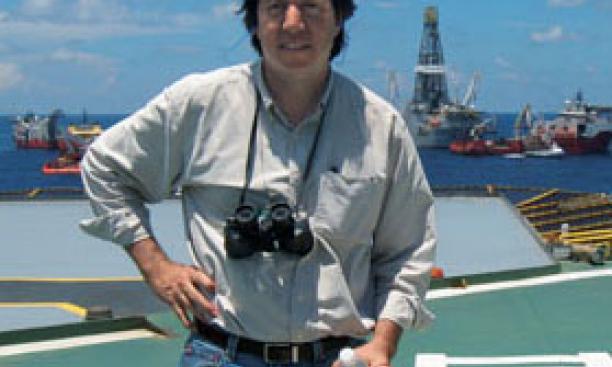

Achenbach’s A Hole at the Bottom of the Sea: The Race to Kill the BP Oil Gusher, published by Simon & Schuster, follows the disaster from just before the blowout in April 2010 through the capping of the well in August. His research included a helicopter ride over the disaster site as the spill was under way, several visits to the “war room” in Houston (the “rabbit warren” where officials of BP and the government developed their strategy to contain the leak) and coverage of multiple investigatory hearings that followed the spill.

He also read 19,000 pages of government e-mail traffic. The e-mails “enabled me to go behind the scenes to see what it was like for these folks, day to day, hour to hour,” he says. “It’s a reminder of how rough it all was. Everyone was groping in the dark.”Achenbach isn’t interested in pointing fingers, but rather in re-creating the events as they happened and reflecting on what can be learned from the disaster. He sees the BP spill as symptomatic of a broader problem: Modern technology is becoming so complex that ordinary individuals cannot adequately understand how things work, especially low-probability, high-risk situations like the BP spill, in which the best-laid backup plans crumbled amid scenarios no one expected.

“If anyone wants to say that BP is evil, stupid, and greedy, I think they miss the bigger picture,” says Achenbach. “We’re living in a highly engineered era where our technology is increasingly complex and vast in scale, and where potential failure looms. That’s not because technology is getting worse, but because it’s getting better.”

This doesn’t mean that everyone needs to know exactly how a blowout preventer works — or how a satellite stays in orbit or how an electrical grid shifts electricity around. “That’s what engineers are for,” Achenbach says. Still, he adds, some knowledge of technology and the language that describes it increasingly is important for ordinary people.

Part of being an informed citizen, he says, “is knowing enough to realize when people are telling you a plausible story or not.”

Louis Jacobson ’92 is a staff writer in Washington with PolitiFact.com.