Last December, Bernard Haykel was conducting research in India when a fruit vendor named Mohammed Bouazizi set himself on fire in a small town in Tunisia — a spontaneous response, it appeared, to degrading treatment by the police and a dearth of opportunities available to a young man like himself.

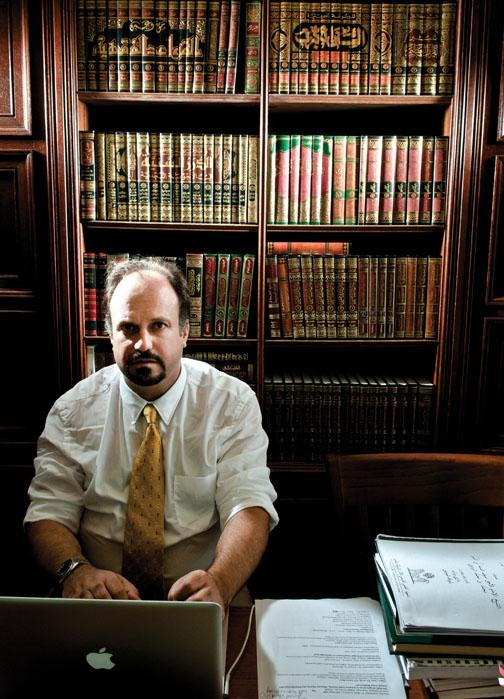

“I heard about it and thought, ‘What an odd thing for an Arab and a Muslim to do,’ because suicide is really prohibited in Islam,” recalls Haykel, a professor of Near Eastern studies. Yet others emulated Bouazizi in the days that followed.

Frustration long has been both palpable and powerful in the Middle East, particularly among the young, but these suicides were “unprecedented,” Haykel says, “a remarkably shocking symbol of resistance” that said, “my frustration has reached such a level that I’m not willing to live in this world anymore.” Haykel, like many observers, had believed the acts would have little effect on regimes insulated from the plaints of their people by oil money and security services. Instead, Bouazizi’s impetuous act set off a dizzying cascade of uprisings that became the “Arab Spring.”

Haykel had thought change in the Middle East would come violently, if at all — that Islamists, possibly al-Qaida, would drive it. Instead, he says, “You had these mass populist movements that didn’t seem to have an ideology, that didn’t have a leadership, that were not afraid to die, that were calling for individual dignity, freedom — not freedom as we understand political freedom, but freedom from the oppression of the state and the petty oppression of the state — the police, and local corrupt officials — for economic dignity and economic opportunity. It was something we hadn’t seen before.”

The professor didn’t sleep for days, lest he miss something. He was overcome with elation — “but also confusion,” he says. His research slowed. He started thinking about rewriting the syllabi for his courses. “It’s been very distracting from my work,” he says, “but I couldn’t not follow it. I just couldn’t.”

It may have distracted Haykel from the work he was doing, but, in a very real way, this was his work. As a regional specialist, a scholar, a writer, a teacher, and a man of Arab descent, he has been trying to understand, perhaps even prepare for, these kinds of events for a long time.

As the Arab Spring erupted, Haykel was on sabbatical, working on a book that will examine the ways in which Saudi Salafis have exported their faith — and their intolerance — beyond Arabia. Theirs is a puritanical, ultraconservative sect that calls on modern-day Muslims to live and practice as the first three generations of faithful — the Salaf al-salih, or “pious ancestors” — did during and after Muhammad’s lifetime. Though relatively small in number, Salafis are found throughout the Middle East, Arabia, and South Asia. Haykel has been studying them for nearly two decades.

Haykel has a broad array of interests and areas of expertise. A conversation with him could well touch on the origins of Islamic jurisprudence, the balance of power in modern-day Yemen, the role of ecology in regional politics, or al-Qaida’s internal feuds. His research is as likely to involve dissecting pre-modern Arabic texts as tracking online chat rooms used by Islamic militants or interviewing al-Qaida recruiters, and he’s as liable to publish his results in scholarly journals as in major media outlets. It’s his work on Salafis, however, a group that exists simultaneously in the current moment and in centuries long past, that best embodies his approach: constant movement between yesteryear and the present day, and a prevailing belief that they’re not as far apart as it first would seem.

“I’m a polyglot,” says Haykel, a child of multiple cultures and multiple identities. He was born in Beirut in 1968. Both his French-Lebanese father, who was raised in Guadeloupe, and his mother, who is American, visited Lebanon for the first time on their honeymoon; captivated by the place, they decided to stay. Their idyll was shattered when civil war erupted when Bernard was 7. Haykel’s father, a surgeon, saw the conflict’s toll every day, while his son saw firsthand how religion could impact daily life when Islamic fundamentalists took over their hometown, Tripoli, and then again, from a remove, when Islamic radicals seized control of Iran in 1979.

In 1984, after Haykel stumbled into a firefight and was nearly killed, his parents sent him to the United States to finish high school. Georgetown followed, then Oxford, where an interest in diplomacy morphed into a fascination with Middle Eastern scholarship. One mentor, Wilferd Madelung, stressed the study of original texts. Another, Paul Dresch, believed social anthropology was key to understanding cultures. Haykel thought both were correct and began applying their methods to field research in Yemen and the study of the Zaydi Shia sect. He says he found Yemen “intoxicating.”

He soon began delving into the life of Muhammad al-Shawkani, an 18th-century Salafi who urged the Muslims of his day to look to the original texts — the Koran and the hadiths, or sayings of the prophet Muhammad — rather than imams and latter-day interpreters to find Islam in its purest form. Haykel’s dissertation became his best-known book, Revival and Reform in Islam: The Legacy of Muhammad al-Shawkani, which shows how al-Shawkani and other Salafis propagated a rigid, radical movement designed to recapture the most unadulterated expression of Islam and to re-educate or expel wayward Muslims — particularly the Shia, whom they viewed as apostates of the worst kind.

To this day, Haykel wrote in 2009, Salafis “seek to reform other Muslims to their own version of Islam, ideally through missionary work but in some cases” — al-Qaida in particular — “through violent action.” The book Haykel is writing contends that despite its focus on Muslims who lived more than 1,000 years ago, the creed is suited to modern Muslims who want something pure, uncorrupted, and ostensibly incorruptible. Salafist belief is anti-hierarchical and thus, Haykel argues, highly appealing to people who grew up under indomitable political hierarchies in the years after secular Arab nationalism failed to deliver on its promises. (There are similarities, he says, to the Tea Party’s harkening back to an imagined “pure” American-ness of the founding fathers.)

He also has written about Salafism’s influence on modern politics; the virulent form practiced by al-Qaida leaders like Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, who targeted Shiites in Iraq; and the manner in which it undermined al-Qaida’s ability to claim a broad constituency. In 2008, he wrote that he’d interviewed a former bodyguard of Osama bin Laden who said that “these younger militants were out of control, unprincipled, uneducated in Islamic law, and incapable of assessing what was in the best interests of the Muslims.” That new breed, he continued, likely would pull further away from the leadership in Pakistan and seek to launch their own attacks on the West — which is precisely what happened.

Collectively, the work earned Haykel a reputation as a versatile scholar who combines classical knowledge with on-the-ground research and access to people who otherwise might not receive a Western academic too warmly. “He is one of the very few people in the world who straddles two connected but very different disciplines: the classical study of Islam — Islamology, if you will — on the one hand, and then contemporary Middle East politics on the other,” says Thomas Hegghammer, a senior research fellow at the Norwegian Defense Research Establishment and a 2007 postdoctoral fellow at Princeton.

“There are a lot of discussions in Washington that bounce around with the same information because people don’t have unique sources,” says Jon B. Alterman ’87, a former State Department official who directs the Middle East Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. “What Bernie brings in is an entirely different data set.”

Haykel came to Princeton from New York University in 2007. He arrived as interest was surging in the regions that Near Eastern studies covers — roughly, North Africa to South Asia, and Turkey and the Caucasus to Arabia and into East Africa. His appointment was part of a larger move in the department to more fully embrace the modern greater Middle East. In came specialists on Iran and Persian studies, on Afghanistan and Pakistan, on Arabia, and specifically on what was happening in these places at that very moment. Haykel was given a means to carry this out when he became director of Princeton’s Institute for the Transregional Study of the Contemporary Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia (TRI), which had been founded in 1994 with a grant from Prince Moulay Hicham Benabdallah ’85 of Morocco to cultivate contemporary Middle Eastern studies. He could tap the talent in many departments to offer courses, bring in speakers, organize conferences, and offer fellowships.

Haykel’s role, he believes, is to be a translator — an explainer — of events. Whether teaching a precept or a graduate seminar, testifying before a congressional panel, or addressing the broader public in print, on television, or in online chats on bloggingheads.tv, Haykel sees his primary task as to explain what is happening and how it happened, and to contextualize the present with informed perspectives rooted in a rigorous study of the past.

“The academics who have taken this region seriously have a great advantage on the rest of us, because they understood Islam or Islamism long before it was a faddish or current topic, so they’re more likely to be immune to history or simple prejudice about the Islamic world,” says Thanassis Cambanis *00, author of A Privilege to Die, a book about Hezbollah. “They’re much more likely to isolate what is important in understanding a phenomenon like the rise of al-Qaida without resorting to simplistic and inaccurate tropes about Islam as a religion or Arab culture, and that’s incredibly helpful.”

When Haykel did begin to speak out, he readily admitted that he had not anticipated what had happened, but said that while the Arab Spring was a pan-Arab event, there were significant differences between countries and there was still great cause for concern. “The toppling in Tunisia and in Egypt is not necessarily a template for other places,” he told PAW late in the summer. “There are other regimes where the societies are structured differently. They’re less homogeneous, they’re more sectarian, where resistance will be much, much tougher and where the game of politics is zero-sum.”

The United States, he wrote, was “blindsided” by these events; the Obama administration’s response “erratic.” The rebels in Libya were nearing the capital, the future in that country — with or without Qaddafi — anything but assured; while the regime in Syria seemingly was bent on answering the question, “How brutal can a regime be in this day and age and get away with it?” Bahrain’s royal family benefited from the patronage of the Saudis, whose troops helped crush demonstrations there. Yemen was continuing toward the brink of chaos, another Somalia in the making, where the regime had atomized old tribal orders and al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula was finding more room to operate. But U.S. policy in the country was centered almost entirely on flying drones overhead and conducting counterterrorism operations.

The Saudis, meanwhile, were backing associates of President Ali Abdullah Saleh (if not Saleh himself), thinking the old regime could maintain the kind of stability that would prevent millions of Yemenis — “hungry, heavily armed, and envious of Saudi wealth,” as Haykel wrote — from pouring across the Saudi border. Both approaches, though, risked further alienating — and possibly further radicalizing — a population already furious about the years of corruption and control it has endured. Furthermore, the country was running out of natural resources, including water. “It’s a tragedy in the making,” Haykel says. “I wish that when either Saudi Arabia or the United States was thinking about Yemen, they weren’t just thinking about the threat of al-Qaida but thinking more holistically about the place.”

The House of Saud was “leading the counterrevolution against the Arab Spring uprisings,” Haykel wrote, due to the same mindset. “The kingdom’s response is centered, as its foreign and domestic policy has long been, on ‘stability.’ The Saudis don’t want anti-Saudi forces, including such enemies as Iran and al-Qaida, to increase their influence in the Middle East.” The reformists were seen as a fifth column; to stave them off, the royals reverted to a familiar mix of religion and largesse. A council of Saudi religious scholars was enjoined to declare that public demonstrations were un-Islamic, Haykel noted, while public salaries were raised, public-sector jobs were added, and new housing units were promised — all moves primarily made to appease young people. (He also pointed out that the nation’s Shia minority started protesting before allying with other would-be reformers, making it easier for the regime to paint its calls for change, and any demonstrations, as Iranian meddling.)

In Egypt, Tunisia, and elsewhere, such short-term strategies, which left larger issues unaddressed, were at the root of the uprisings. “The thing about Saudi Arabia is, essentially, you have this old leadership that has decided to kick the can down the road and to put off problems that are inevitably going to emerge, specifically with this youth bulge — the jobs they need to find, the diversification of the economy that they need to do — in other words, to move away from such heavy dependence on oil revenues,” he told NPR in June.

Across the region, Haykel tells PAW, “The demands are the same everywhere. The demands are that people as individuals don’t want to be brutalized by their own state. They want economic opportunity. There’s a focus on individual rights over collective rights and collective forms of identity.” The key to the Arab Spring, though, still is Egypt, the largest and most historically significant of the countries affected. Even measured progress toward a more open, accountable state, Haykel says, “will be hugely important because the others in the region — Saudis, Jordanians, Syrians, and Algerians — will say, ‘If the Egyptians can have this, why can’t we?’” But, he adds, “The problem with Egypt is, it has a population of 80-plus million now, and it’s still growing. And how are they going to produce the jobs for these people? Unless the West and the Gulf countries — Saudi and others — really help Egypt along, it might end up becoming an incredibly disappointing place for ordinary Egyptians, who then might turn to more radical forms of politics.”

After bin Laden was killed early May 2, Haykel warned that “political Islam or Islamists, a much broader current than al-Qaida, is far from over,” and pointed out that Salafis were making inroads into places like Gaza and Jordan. In Egypt, too, the largest demonstration since Mubarak’s fall, in July, was dominated by Islamists demanding that religion be the basis for the new constitution. The Arab Spring was a modern movement with modern goals, but Haykel’s work helps him understand that in the ensuing chaos, the old ways — of culture, politics, and religion, including Salafism – could fill the vacuum. What’s more, he posits, America’s conduct in the region also could bring about a reckoning. “I find it really hard to believe that the last 10 years of war between the United States and al-Qaida, in which tens of thousands of Muslims have been killed, principally by Americans, but also by al-Qaida, is just going to be forgotten now that the Arab Spring is upon us,” he says. “I can’t imagine that there isn’t going to be a deep and nasty legacy, and kind of a vendetta, feud-style mentality that will remain engrained in the minds of many al-Qaida supporters and even ordinary Muslims for the death of so many people.”

In August, Haykel traveled to Lebanon. Confusion still reigned in the region, he said by phone from Beirut, and people were feeling their way through. In his way, he was doing the same, trying to grasp what was unfolding, and pondering how to present it to students this fall. His simultaneous pursuit of several strains of study — across borders, religious divides, disciplines, and centuries — means he never will be totally settled. The comparisons and juxtapositions can be jarring, but they yield, he believes, greater insight. For a region, confusion is deeply unsettling. For his work, Haykel says, it’s necessary. “It’s not comfortable, but I would much rather have that and reach a reasoned conclusion about a set of events than to be fixated from the beginning,” he says. “I think confusion is underrated.”

Phil Zabriskie ’94, the managing editor for publications at Doctors Without Borders-USA, has been a staff writer at Time magazine and a freelancer for other publications.

Haykel came to Princeton from New York University in 2007. He arrived as interest was surging in the regions that Near Eastern studies covers — roughly, North Africa to South Asia, and Turkey and the Caucasus to Arabia and into East Africa. His appointment was part of a larger move in the department to more fully embrace the modern greater Middle East. In came specialists on Iran and Persian studies, on Afghanistan and Pakistan, on Arabia, and specifically on what was happening in these places at that very moment. Haykel was given a means to carry this out when he became director of Princeton’s Institute for the Transregional Study of the Contemporary Middle East, North Africa and Central Asia (TRI), which had been founded in 1994 with a grant from Prince Moulay Hicham Benabdallah ’85 of Morocco to cultivate contemporary Middle Eastern studies. He could tap the talent in many departments to offer courses, bring in speakers, organize conferences, and offer fellowships.

Haykel’s role, he believes, is to be a translator — an explainer — of events. Whether teaching a precept or a graduate seminar, testifying before a congressional panel, or addressing the broader public in print, on television, or in online chats on bloggingheads.tv, Haykel sees his primary task as to explain what is happening and how it happened, and to contextualize the present with informed perspectives rooted in a rigorous study of the past.

“The academics who have taken this region seriously have a great advantage on the rest of us, because they understood Islam or Islamism long before it was a faddish or current topic, so they’re more likely to be immune to history or simple prejudice about the Islamic world,” says Thanassis Cambanis *00, author of A Privilege to Die, a book about Hezbollah. “They’re much more likely to isolate what is important in understanding a phenomenon like the rise of al-Qaida without resorting to simplistic and inaccurate tropes about Islam as a religion or Arab culture, and that’s incredibly helpful.”

When Haykel did begin to speak out, he readily admitted that he had not anticipated what had happened, but said that while the Arab Spring was a pan-Arab event, there were significant differences between countries and there was still great cause for concern. “The toppling in Tunisia and in Egypt is not necessarily a template for other places,” he told PAW late in the summer. “There are other regimes where the societies are structured differently. They’re less homogeneous, they’re more sectarian, where resistance will be much, much tougher and where the game of politics is zero-sum.”

The United States, he wrote, was “blindsided” by these events; the Obama administration’s response “erratic.” The rebels in Libya were nearing the capital, the future in that country — with or without Qaddafi — anything but assured; while the regime in Syria seemingly was bent on answering the question, “How brutal can a regime be in this day and age and get away with it?” Bahrain’s royal family benefited from the patronage of the Saudis, whose troops helped crush demonstrations there. Yemen was continuing toward the brink of chaos, another Somalia in the making, where the regime had atomized old tribal orders and al-Qaida in the Arabian Peninsula was finding more room to operate. But U.S. policy in the country was centered almost entirely on flying drones overhead and conducting counterterrorism operations.

The Saudis, meanwhile, were backing associates of President Ali Abdullah Saleh (if not Saleh himself), thinking the old regime could maintain the kind of stability that would prevent millions of Yemenis — “hungry, heavily armed, and envious of Saudi wealth,” as Haykel wrote — from pouring across the Saudi border. Both approaches, though, risked further alienating — and possibly further radicalizing — a population already furious about the years of corruption and control it has endured. Furthermore, the country was running out of natural resources, including water. “It’s a tragedy in the making,” Haykel says. “I wish that when either Saudi Arabia or the United States was thinking about Yemen, they weren’t just thinking about the threat of al-Qaida but thinking more holistically about the place.”

The House of Saud was “leading the counterrevolution against the Arab Spring uprisings,” Haykel wrote, due to the same mindset. “The kingdom’s response is centered, as its foreign and domestic policy has long been, on ‘stability.’ The Saudis don’t want anti-Saudi forces, including such enemies as Iran and al-Qaida, to increase their influence in the Middle East.” The reformists were seen as a fifth column; to stave them off, the royals reverted to a familiar mix of religion and largesse. A council of Saudi religious scholars was enjoined to declare that public demonstrations were un-Islamic, Haykel noted, while public salaries were raised, public-sector jobs were added, and new housing units were promised — all moves primarily made to appease young people. (He also pointed out that the nation’s Shia minority started protesting before allying with other would-be reformers, making it easier for the regime to paint its calls for change, and any demonstrations, as Iranian meddling.)

In Egypt, Tunisia, and elsewhere, such short-term strategies, which left larger issues unaddressed, were at the root of the uprisings. “The thing about Saudi Arabia is, essentially, you have this old leadership that has decided to kick the can down the road and to put off problems that are inevitably going to emerge, specifically with this youth bulge — the jobs they need to find, the diversification of the economy that they need to do — in other words, to move away from such heavy dependence on oil revenues,” he told NPR in June.

Across the region, Haykel tells PAW, “The demands are the same everywhere. The demands are that people as individuals don’t want to be brutalized by their own state. They want economic opportunity. There’s a focus on individual rights over collective rights and collective forms of identity.” The key to the Arab Spring, though, still is Egypt, the largest and most historically significant of the countries affected. Even measured progress toward a more open, accountable state, Haykel says, “will be hugely important because the others in the region — Saudis, Jordanians, Syrians, and Algerians — will say, ‘If the Egyptians can have this, why can’t we?’” But, he adds, “The problem with Egypt is, it has a population of 80-plus million now, and it’s still growing. And how are they going to produce the jobs for these people? Unless the West and the Gulf countries — Saudi and others — really help Egypt along, it might end up becoming an incredibly disappointing place for ordinary Egyptians, who then might turn to more radical forms of politics.”

After bin Laden was killed early May 2, Haykel warned that “political Islam or Islamists, a much broader current than al-Qaida, is far from over,” and pointed out that Salafis were making inroads into places like Gaza and Jordan. In Egypt, too, the largest demonstration since Mubarak’s fall, in July, was dominated by Islamists demanding that religion be the basis for the new constitution. The Arab Spring was a modern movement with modern goals, but Haykel’s work helps him understand that in the ensuing chaos, the old ways — of culture, politics, and religion, including Salafism – could fill the vacuum. What’s more, he posits, America’s conduct in the region also could bring about a reckoning. “I find it really hard to believe that the last 10 years of war between the United States and al-Qaida, in which tens of thousands of Muslims have been killed, principally by Americans, but also by al-Qaida, is just going to be forgotten now that the Arab Spring is upon us,” he says. “I can’t imagine that there isn’t going to be a deep and nasty legacy, and kind of a vendetta, feud-style mentality that will remain engrained in the minds of many al-Qaida supporters and even ordinary Muslims for the death of so many people.”

In August, Haykel traveled to Lebanon. Confusion still reigned in the region, he said by phone from Beirut, and people were feeling their way through. In his way, he was doing the same, trying to grasp what was unfolding, and pondering how to present it to students this fall. His simultaneous pursuit of several strains of study — across borders, religious divides, disciplines, and centuries — means he never will be totally settled. The comparisons and juxtapositions can be jarring, but they yield, he believes, greater insight. For a region, confusion is deeply unsettling. For his work, Haykel says, it’s necessary. “It’s not comfortable, but I would much rather have that and reach a reasoned conclusion about a set of events than to be fixated from the beginning,” he says. “I think confusion is underrated.”

Phil Zabriskie ’94, the managing editor for publications at Doctors Without Borders-USA, has been a staff writer at Time magazine and a freelancer for other publications.

Near Eastern studies Ph.D. candidate Gregory Johnsen has been traveling to and writing about Yemen for more than a decade:

“There’s a real danger that the U.S. and countries in the region — Saudi Arabia and the GCC [Gulf Cooperation Council] — are missing a unique window of opportunity to press for positive change within Yemen. If the U.S. and the GCC countries aren’t able to take advantage of that, then we’re going to hear about Yemen for some time to come in the news. We’re going to be reading about it for quite some time, and it’ll be for all the wrong reasons.”

Associate professor Michael Reynolds focuses on the Caucasus and Turkey:

“For many Muslims in the Middle East and elsewhere, there was always kind of a question: Can you be an authentic Muslim and also be a liberal democrat? … [In] today’s Turkish model, [run by the ruling party] the AKP, the big hope is that it is sending the message that you don’t need to choose between these two things. ... I hope Turkey will serve as an inspiration, but I think it would be a mistake to assume Turkey is a model for these countries because the conditions inside are so different.”

Michael Barry is a lecturer in Near Eastern studies with a specialty in Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan:

“There’s going to be a period of tremendous flux in which there is no possible doubt that the Sunni Islamists and their Pakistani allies in one way or another are going to try to preserve influence or increase it. That doesn’t mean that they will. ... That’s why I don’t think we can afford to take away our eyes from this Pakistani-Afghan nexus.”

Jon B. Alterman ’87 is director of the Middle East Program at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies:

“There’s an underlying trend, which is that a combination of education and technology empowers individuals. ... That’s going to affect the way societies work. And I would argue that it will mean both less social control, but also you will have a constant empowered opposition that will try to be disruptive of the mainstream.”

Associate professor of politics Amaney Jamal directs the Workshop on Arab Political Development:

“Democratization doesn’t happen overnight. Between protest episodes and the consolidation of democratic institutions, you could see a decade, or two decades. There’s going to be some turmoil in the Arab world. These are not going to be smooth transitions.”

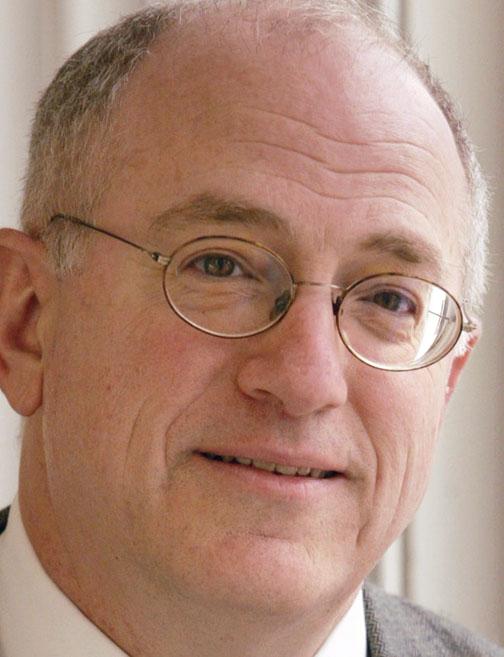

Woodrow Wilson School professor Daniel Kurtzer has been U.S. ambassador to Egypt and to Israel:

“There are two critical things for American policy. ... One is to see whether or not the Muslim Brotherhood will represent a moderate force within society or whether it’s the beginning of a much more dramatic Islamization, which could be inimical to our interests. No. 2 is the Egyptian economy, which has been at a standstill since January. If it doesn’t pick up soon and forcefully, then the political issues will give way to very significant economic and social issues, and that’s not going to be healthy.”