One of nature’s most graceful creatures provided inspiration for the innovative robots that were tested last May in a competition between students at Princeton and the University of Virginia. The two teams are working to create a robot that can glide through the water as swiftly, and maneuver as efficiently, as a manta ray. If successful, the “manta bot,” as it sometimes is called, could provide important benefits for the U.S. Navy.

When he returned to Princeton, Smits mentioned his observations to Hilary Bart-Smith, then a postdoctoral researcher who was working on the design of airplane wings, and suggested that she instead try designing wings for an autonomous underwater vehicle that could ply the ocean as a ray does. Four years ago, the Office of Naval Research solicited proposals for “bio-inspired” sea vehicles of just the type that Bart-Smith — by then an associate professor at Virginia — was working on. The two professors applied together and were awarded a five-year grant of $6.5 million in 2008.

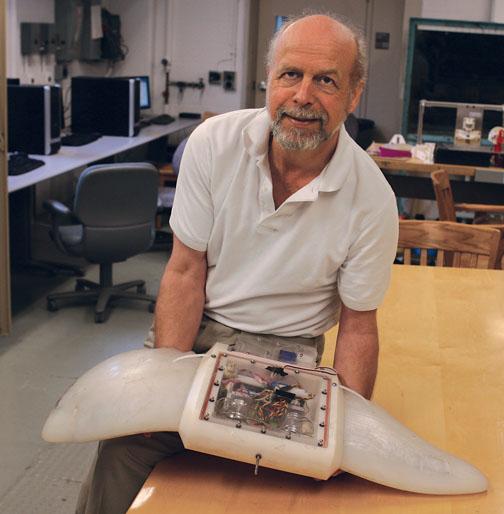

Smits and Bart-Smith decided to arrange a competition between their students to see who could design the best manta bot. Mohammad Javed ’11, a mechanical engineering major, took on the project as a senior thesis and represented Princeton. He designed a robot using a single sheet of plastic. Each fin contains four very thin steel cables that radiate from a center point and attempt to mimic the way a manta moves when it swims. He added a horizontal rudder to increase its maneuverability. The center of the robot contains a motor, sensors, and a computer that receives signals telling it what to do.

The competition was held in a tank at the U.S. Naval Surface Warfare Center near Washington. Javed and his Virginia competitors each were given an hour to have their robots perform several tasks that included moving over and under a submerged bar, diving to the bottom and resurfacing, making the tightest possible turn, and swimming as quickly as possible in a straight line.

Although Javed’s ray swam well, motors that powered the fins overheated at one point. Later in the competition, the bot crashed to the bottom of the testing tank and could not resurface. However, both Princeton and Virginia succeeded in “achieving ray-like propulsion,” in the words of one of the judges, and the contest ended in a tie.

Javed is now working for the oil-industry supplier Schlumberger in the United Kingdom, while the manta bot sits in a campus laboratory, waiting, Smits says, “for someone to give it some loving attention.” The bot still needs work on depth sensors, propulsion, accelerometers, and programming, he says — the perfect challenge for a student in search of a thesis project this year.