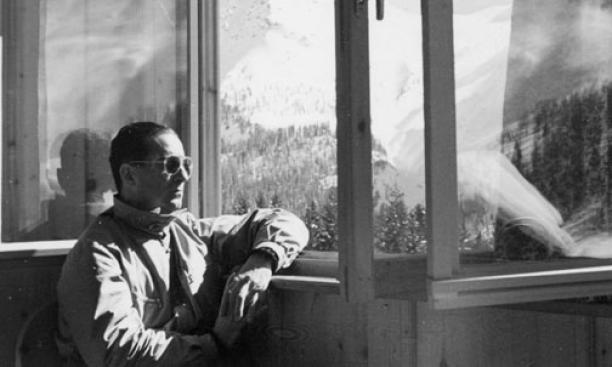

Try as one might, it is difficult to take the full measure of Moe Berg ’23 — and one suspects that is how Berg wanted it. The pieces of his life do not always seem to fit: He was a linguist who became a major-league baseball player, a nuclear spy who spent most of the last two decades of his life practically homeless. Berg, who died in 1972, has been the subject of two biographies, yet he remains an enigma.

Those hoping to understand this complicated man might start with a large collection of Berg’s papers, which were donated recently to the University. Some of those papers, along with several items of Berg memorabilia, are part of a Firestone Library exhibit that runs through Aug. 5.

Berg straddled several worlds without being completely at home in any of them. The child of Jewish Russian immigrants, he was a social outsider in the WASPy Princeton of the early ’20s, but he was a true student-athlete who knew Sanskrit and a half-dozen other languages and was a star shortstop on the baseball team. The Brooklyn Robins signed Berg less than a month after graduation and put him in their lineup the next day.

He spent parts of 15 seasons with five major-league teams, almost all of them as a backup catcher. Berg had a rifle arm but a banjo bat, hitting .243 for his career with only six home runs. Told that Berg spoke seven languages, a teammate once remarked, “Yeah, and he can’t hit in any of them.”

Casey Stengel once called him “the strangest man ever to play baseball,” and Berg’s papers suggest Stengel was right. The papers include many of Berg’s classified World War II reports, his employment applications to the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and the CIA, scraps of an unfinished memoir, a copy of a baseball contract, travel receipts, photographs, and even letters from a girlfriend.

Berg spent the winter after his first season taking classes at the Sorbonne. In 1926, he skipped two months of the season to finish his first year of law school. In 1934, Berg joined Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig on an All-Star team that visited Japan, but also struck a deal to film the tour for a newsreel company and took movies of the Tokyo skyline and harbor. In later years, Berg liked to boast that the Navy relied on that footage to plan Jimmy Doolittle’s 1942 bombing raid, but this seems to have been a tall tale.

The facts of his life story were interesting enough. During World War II, Berg’s linguistic talents made him attractive to the OSS, the predecessor of the CIA. The OSS dropped Berg into Yugoslavia to report on local resistance groups, and later asked him to interview Italian scientists. In his most dangerous assignment, Berg posed as a student and attended a lecture given in Switzerland by Germany’s top nuclear physicist, Werner Heisenberg. Berg went armed with a pistol and a cyanide capsule. If Heisenberg’s lecture convinced him that the Germans were close to developing an atomic bomb, Berg was to assassinate Heisenberg and use the cyanide to kill himself.

Although the CIA recruited Berg for at least one assignment after the war, the agency declined his application for full-time work, partly because of his increasingly eccentric behavior. For the rest of his life, he had trouble holding a job and lived with relatives.

After Berg’s death, his papers passed through several hands before William Sear, an Atlanta baseball collector, bought them in 2001. Sear gave them to Princeton last year.

Several of those items are part of the current Firestone exhibition, “A Fine Addition: New and Notable Acquisitions in Princeton’s Special Collections,” which also includes Hemingway and Fitzgerald letters, a 16th-century medical treatise, and a rare 13th-century gold coin.

Berg would have appreciated being in such company. Nicholas Dawidoff, who wrote the 1994 biography The Catcher Was a Spy, believes that Berg was haunted by a sense that he had failed to live up to his early promise. “To avoid exposure as a charlatan,” Dawidoff writes, “Berg lived a bedouin life, ever on the move, always avoiding sustained relationships where people might get a clear look at him.”

Journalist Lou Jacobson ’92, a longtime Berg buff who co-produced a 2010 podcast about him (available at http:// www.baseballphd.net/tag/louis-jacobson), agrees. “He was a genius,” Jacobson says, “but a complex and sometimes flawed person.”