Last time, you doubtless recall, I promised to talk about tennis or some other springtime diversion in this edition, especially for those who may not get their jollies from quantum mechanics. Fortunately, the nice folks down at Lenz Tennis Center have given us plenty to talk about, considering both the improving stature of the tennis teams and their spiffy new accoutrements amid the courts. The new structure is the Cordish Family pavilion, tennis being a fine family pastime – more so than quantum mechanics, I guess – and the entire clan (including tennis alums Blake Cordish ’93 and Reed Cordish ’96) having been kindly disposed toward endowing improved locker, team, coaches’ and viewers’ facilities for the varsity courts, adjacent to the fine new soccer complex and the still-improving lacrosse/field hockey complex south of Poe Field.

Speaking of which, the lacrosse teams are playing on a new surface this year, spiffy Field Turf (the same stuff that now adorns Powers Field at Princeton Stadium), that being the current state-of-the-art for bigtime collegiate lacrosse teams in New Jersey or further north, since they bizarrely play real competitive games in February when actual grass has the sense to be dormant. As you know, I’m the last apologist on earth for the Good Old Days, with their poignant touches of tuberculosis and Wite-Out, but here at History Central we do know irrationality when we see it, and February lacrosse qualifies without much debate. Meanwhile, next door on Bedford Field, a new field hockey AstroTurf surface will be installed by August, since high-powered collegiate field hockey now requires a different artificial grass to be competitive than the one on the lacrosse field, and thus the three nationally-ranked programs end up on two fields instead of one. (Remember the part about irrationality?)

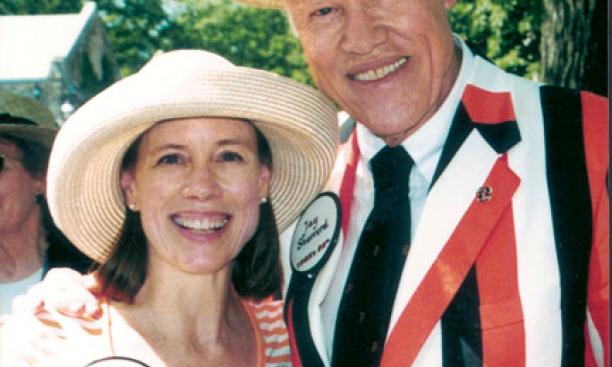

The good news here – aside from all three teams remaining nationally competitive – is that the folks who have donated the funds for the new lacrosse surface at the Class of 1952 Stadium admirably have chosen to name it after a true alumni hero, the legendary late Jay Sherrerd ’52. For those who were not so fortunate as to know Jay, he was a Philadelphia financier who co-founded an investment management firm that later was sold to Morgan Stanley. But for decades he spent huge amounts of time working for Princeton, where he appeared always to be involved in three or four simultaneous major projects; in addition to sitting on Princo’s board, he oversaw the Robertson endowment, had major roles in three University capital campaigns, and spearheaded the Class of ’52’s wildly successful annual-giving campaigns – it’s the second-highest donating class in history – as well as the class’s campaign to build 1952 Stadium, which partly recognized the sea change brought to lacrosse at Princeton by coaches Bill Tierney and Chris Sailer. He also donated directly to Princeton’s next generation; namely, his daughters Susan Sherrerd ’86 and Anne Sherrerd *87, the first graduate alum to serve as president of the University’s Alumni Association. Amid all of this, he was a trustee for a very unusual 20 years, chairing the board’s resources committee twice. His generous bequest at his death in 2008 is the basis for the new Sherrerd Hall on Shapiro Walk, where ORFE and even more esoteric systems-type folks hang out. Most important, he was a happy warrior, with a great sense for people (he barely knew me, but always called me by name) and a quiet grin no matter what the multi-million-dollar occasion; he was working twice as hard as anyone else in the room, and enjoying it twice as much too, infectiously.

Here at History Central, recalling Jay and his legacy brings up a fascinating parallel that is almost unbelievably apt. The term legendary has been used before regarding another trustee, namely Dean Mathey 1912, and despite the fact that he now appears here with a four-digit class numeral it applies today. Like Sherrerd, his day job was on Wall Street – he was a lead partner at Dillon Read – but his home and his rapt attention were in Princeton, with every facet and detail of the University’s operation and advancement throughout the mid- 20th century. Twice intercollegiate tennis doubles champion (remember, this is a tennis column) and Phi Beta Kappa as an undergraduate, by the time he was 37 he was a University trustee, and reputedly saved the endowment by bailing out of stocks and into bonds in 1928, then reversing course and putting 80 percent of it back into stocks in 1942, thus catching the market going in both directions. Remaining on the board for an awe-inspiring 34 years, he sat at one time on every one of its nine standing committees, and chaired both the investment committee and his true love, buildings and grounds, where he served his entire 34 years; he made countless donations to the Princeton landscape, many in support of the great Beatrix Ferrand, from the brick wall behind Maclean House in memory of his father-in-law to the Class of 1912 pavilion between Poe Field and the soccer complex, in memory of his classmate Sanford White 1912. Owning a local estate and sensitive to the expensive Princeton real estate market, he also was a champion of subsidized faculty housing, and donated a housing complex near the Grad College in memory of his first wife. He was on the trustee committee that greeted President Harold Dodds *1914 in 1933, and again President Robert Goheen ’40*48 in 1957. Goheen explained Mathey’s dedication, largesse, and length of service thus: “Dean liked people.”

The startling and instructive comparison is this: When Mathey died in 1971, there was not a single physical item on the campus named for him; the same was true of Jay Sherrerd when he died 37 years later. The University, of course, eventually corrected that by naming Dean Mathey Court (appropriately, faculty housing) and Dean Mathey College for him, as it subsequently has honored Sherrerd with the ORFE building (although he originally objected to the idea) and the lacrosse field, but we should consider that what these giants of Princeton volunteerism accomplished was not for recognition – they demonstrably avoided it – but for the good of their chosen beneficiaries: all of us. And while it’s highly important that we now have their names prominently around us to recall what they stood for, they actually valued much more profound ideas. Their modesty bespeaks it, eloquently.

“I believe the causes of this loyalty to our private colleges,” said Mathey (in words that I swear I can hear coming from Jay Sherrerd’s lips), “go back to the first law of nature, namely survival. For, it seems to me we sense how fleeting all things are, not only the things we build with our hands, but life itself and even our posterity. And along with this we also sense, subconsciously perhaps, that the great seats of learning . . . some established as far back as the eleventh century – have withstood the ravages of time better than any other thing to which we ourselves may contribute.” From Mathey’s first visit to Princeton for a high school tennis tournament in 1907 until Sherrerd’s death in 2008, the University flourished for a century, in no small part because of the two of them.

About a hundred yards away from the new Sherrerd Field is the tennis pagoda (remember, this is a tennis column), which has never had a name. Built originally south of Dillon Gym amid the old courts in 1960, it offered the same great view of matches as the spiffy new Cordish complex, but without the amenities. When Whitman College wiped out the old pagoda courts, it meticulously was moved south to its new home, despite the newer Lenz Center already having one (now replaced by Cordish). Aside from being a nod to team tradition, the old tennis pavilion has another notable characteristic: It’s the gift of Dean Mathey and fellow tennis captain Joseph Werner ’21, and it includes carved in stone the words of legendary (there’s that word again) sportswriter Grantland Rice that appear at the beginning of this column. If there’s one thing that should be remembered of both Mathey and Sherrerd, it’s that they knew full well that in the end, the game wasn’t tennis or lacrosse or financial engineering; that is why they played it so well.