Last year, working in Parramos, Guatemala, Princeton in Latin America fellow Cindy Kroll ’11 spent half of each day as an English and math teaching assistant in a junior high school and half a day helping a public-health clinic. As if that weren’t enough to fill her schedule, Kroll also volunteered to teach English to fifth- and sixth-graders.

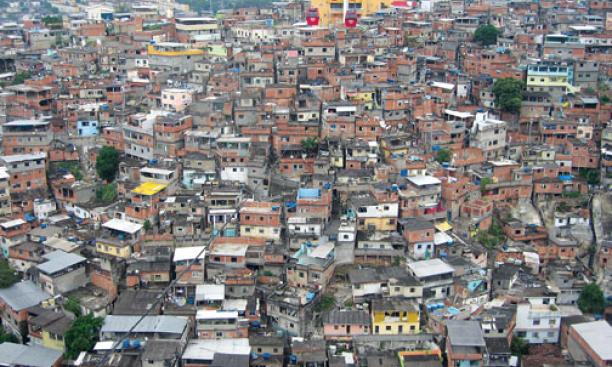

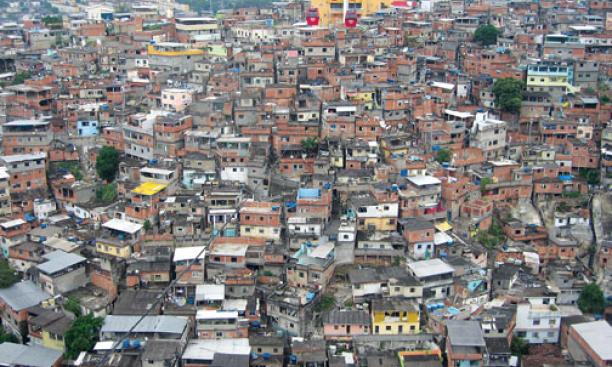

Hank Song ’11, a PiLA fellow with Associação Saúde Criança (Child Health Association, or ASC) in Rio de Janeiro last year, did more than work as a grant writer and fundraiser. As his Portuguese improved, Song volunteered with ASC’s family-care center and visited some of Rio’s most underprivileged favelas, or shanty towns.

Laura Morales ’09, in Peru during 2009–10 as a biologist and assistant researcher at a remote research station in the cloud forest of the eastern Andes, started a small museum collection with bones, pictures of animal tracks, flowers, stuffed animals, etc. She skinned a road-killed skunk she found so that she could add its pelt — a hit with children who saw it — to her collection. “Skinning a skunk ... there’s something they don’t teach you at Princeton,” Morales said in an email.

This year, the 10th anniversary of PiLA’s founding, 33 fellows are at work in 15 countries. If David Atkinson ’63, president of PiLA’s board of directors has his way, by 2020 the organization will have 100 fellows working in education, health, human rights, microenterprise, environmental protection, and the arts.

“We want to have a broad representation throughout the entire region,” said Atkinson, who grew up in Brazil. “We also need to do something in Haiti, and we’d like to move into the English-speaking Caribbean.”

His enthusiasm and ambitions for PiLA, which started with just two fellowships in 2003–04, are shared by donors such as international economist Arminio Fraga *85 of Brazil, who will be honored for his support at a 10th-anniversary celebration at New York’s Racquet and Tennis Club Oct. 25. PiLA has increased its presence in Brazil, thanks to Fraga, and this year six fellows are working in health and education in Rio’s slums.

Similar to Princeton in Asia and Princeton in Africa in its mission of service, PiLA was launched in the fall of 2002 by Daniel Pastor ’03 and Allen Taylor ’03 with support from students, alumni, and faculty. Though the University provides office space and a website, PiLA relies entirely on donations.

Applications for PiLA fellowships have burgeoned: 290 last year, up 100 from the previous year. Executive director Claire Brown ’94 attributes the jump to a weak job market for recent graduates combined with an increase in available fellowships — six to eight more each year. Of the approximately 150 fellows who have participated, slightly more than half are Princetonians.

Connections that fellows make in Latin America often go beyond the year they spend with PiLA. Morales, who immigrated to the United States from Colombia as a child, said she joined PiLA because she “didn’t want to be part of the loss of human capital from the region.” Now a graduate student at the University of California, Davis, she continues to visit Peru for her work in restoration ecology.

Attorney Adam Abelson ’05 says his work with Human Rights Watch in Chile fueled his interest in international law and his concern about the “potential for abuses” of government power. “My work in Chile continues to inform my work and my worldview,” Abelson said.

Though fellowships last only a year, Atkinson says it’s not unusual for partner organizations to hire participants after their year is over. Hank Song, for example, hopes to become a physician working with underserved populations. But for now he’s still in Rio, developing a framework for international volunteer participation with ASC.

“I feel extremely fortunate to have been able to volunteer with Saúde Criança,” Song said in an email. “The opportunity to talk to and form real connections with people from starkly different backgrounds and from an entirely different continent and culture is an experience that has shown me the importance of a global perspective and an open mind.”