From 1912, there’s the only surviving recording of America’s biggest burlesque and vaudeville star of the 19th century, Lillian Russell. Even older, there’s a tiny snippet of sound from Thomas Edison’s laboratory, one of the inventor’s staff members singing a bit of “Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star,” recorded in 1888 on a tin cylinder meant to be part of a child’s talking doll — the earliest known commercial sound recording.

But of all the finds and treasures of sound in the Library of Congress’ vast vaults of tape, records, and discs, the one James Hadley Billington ’50 finds most moving is the recording of voices of former American slaves, interviewed in the 1930s by the Works Progress Administration.

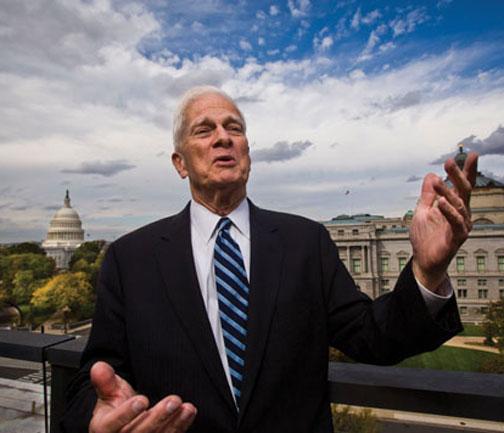

“There’s a big difference between reading about it and hearing somebody telling you their story,” says Billington, a former Princeton history professor who is marking 25 years as the Librarian of Congress. Each year, the library adds 25 pieces of sound to the National Recording Registry, a hall of fame of sorts that is the audio expression of the library’s main mission, as Billington puts it, “to be a mint record of the cultural and intellectual achievements of the American people.”

This year’s additions to the decade-old registry include the Edison cylinder — discovered in a desk in 1946 but unplayable until last year, when digital mapping tools developed by the library and the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory scanned the 5/8-inch-wide surface to unlock the strains of “Twinkle, Twinkle.” “Green Onions” by Booker T. & the MGs was chosen both for its infectious tune and because the rhythm-and-blues group was racially integrated — a rarity when the song came out in 1962. The Vince Guaraldi Trio’s A Charlie Brown Christmas was selected because it introduced jazz to millions of Americans in 1965 both through the TV broadcasts of the animated Peanuts special and through radio play of the “Linus and Lucy” theme; Donna Summer’s 1977 hit, “I Feel Love,” pointed the way from disco to electronica and became a gay anthem.

Overseeing these selections is Billington, who — long before he was a librarian — was one of the nation’s pre-eminent historians of Russia, as he remains today. For nine years, he taught Russian history at Princeton, following his older brother, David, onto the faculty. (David Billington ’50 retired in 2010 after 50 years as a Princeton professor of civil and environmental engineering.) James Billington studied Russian history as a Rhodes scholar at Oxford and went on to write five books on the topic, to found the Kennan Institute for Advanced Russian Studies at the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars (where he was director from 1973 to 1987), and to accompany President Ronald Reagan to the Soviet Summit in Moscow in June 1988, as the Cold War began to wind down. Through all those years, he has been a powerful advocate for international education and exchange — of both people and cultural materials.

During his long tenure at the helm of the world’s largest library, Billington has moved the Library of Congress into millions of American homes with a deep digital catalog of manuscripts, photos, maps, and video, in addition to registries of American sound and film treasures. He has enabled voters to keep tabs on their representatives in Washington with digital and ever-more-detailed connections to the workings of Congress.

“The American public owes a lot to Jim Billington,” says Princeton University Librarian Karin Trainer, noting the digital collections he created. Her own favorites, she says, are the American Memory Project, which contains documents, photographs, videos, recordings, and maps, “with something of interest for everyone from schoolchildren to prize-winning senior scholars”; and the National Digital Newspaper Program, through which readers can search the contents of 19th- and 20th-century American newspapers.

The Recording Registry — like the older National Film Registry, to which selections will be added in December — serves all three of the library’s chief goals: to acquire, preserve, and make accessible to the public the heritage of a nation that “tends to be a throwaway society,” Billington says. Still lean and energetic at 83, he presides over the Library of Congress from a rooftop office with glorious views of the Capitol Dome out one window and the library’s distinctive cupola out the other.

Billington, whose own musical experience consists of working as a “super” — an amateur, “supernumerary” actor — in opera productions in his native Philadelphia during his years at Princeton, meets each year with a panel of experts on music, sound, and preservation. The panel nominates recordings for the registry, and Billington gives final approval. He nudges the panel to broaden the definition of important sounds beyond songs and speeches — to include, for example, the wail of a steam-powered foghorn that was a daily part of the lives of those who lived near Lake Michigan between 1906 and 1981, or the song of the humpback whale, a recording that enjoyed a burst of popularity in the 1960s and turned popular opinion against the killing of whales. The great majority of the 350 selections in the registry are musical compositions, but some spoken-word and natural-sound recordings are added each year. (To nominate a recording for inclusion in the registry, go to www.loc.gov/nrpb.)

The idea, Billington says, is not to “just engage in nostalgia or fulfill a scholar’s desire to preserve everything,” but to capture and explain American history through the sounds that made a difference in both high and pop culture. (Alas, only some snippets of the recordings on the registry are available online because of rights issues, but the library is working to win permission to put more of the nation’s aural history on its website.)

“The amazing thing about American music is it’s broken down the division between what’s classical and what’s popular,” says Billington, pointing to the library’s collections of the works of Frank Sinatra, the Gershwin brothers, and Victor Herbert to show how artists used classic forms and blended different ethnic traditions to create new genres.

A quarter-century into his tenure, Billington still gets excited enough to leap out of his chair as he describes the library’s latest project, an effort to “bypass the whole education bureaucracy and get our cultural heritage out to kids in K-12 with an online history of America through song,” a site that’s expected to be available around the end of this year.

Even as Billington has helped focus scholars, librarians, and readers around the world on the huge opportunities made available by the information revolution, he also has insisted that Americans think seriously about what we’re at risk of losing as we embrace new media. As readers move from reading printed books to zipping around the infinite library of the Web, Billington worries that the basic building block of our intellectual and cultural history — the sentence — is losing its central position. The library proudly announced in 2010 that it had acquired every public tweet tweeted since Twitter’s inception in March 2006 — billions of them, to be archived digitally — in a process still in the early stages. But at the same time, Billington wonders what communicating in 140-character blurts is doing to the ability of Americans to express themselves in linear fashion.

“Is the new technology moving us more toward plebiscite democracy?” he asks. “Are we losing representative government?

“Serious argument and discourse were made possible by the sentence,” he says. “Now, on chat rooms and Twitter, you have combinations of acronyms. I’m a big believer that conversations with mute authors of the past are better than the noise of debates filled with slogans or chat rooms filled with people who haven’t read anything.”

Relying in part on his 12 grandchildren to stay up to the minute on technological change, Billington is no Luddite; he presses the library’s curators to take advantage of social media to push holdings out to users wherever they may be. He has no plans to retire: There’s more to be done, he says, “to preserve the values of the book culture while incorporating the heightened possibilities for greater knowledge offered by new technologies.”

That’s a challenge facing both the library and the nation, he says. As readers’ attention spans shrink and Google’s algorithms take the place of human connection, Billington fears, “it may soon be as difficult to read a Dickens novel as it is for us now to read Beowulf.”

Marc Fisher ’80 is a senior editor at The Washington Post.