PAW ARCHIVE

Search PAW’s Archive

2025

February 2025

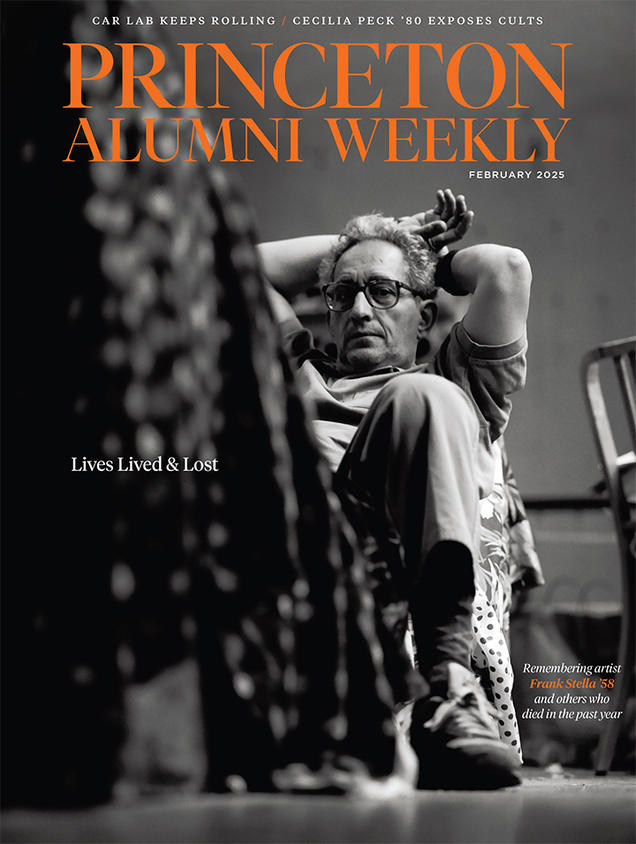

Lives Lived & Lost

January 2025

The 25 Greatest Princeton Athletes

2024

December 2024

Hidden heroines; U.N. speaker controversy; Kathy Crow ’89’s connections

November 2024

Princetonians lead think tanks; the perfect football season of 1964; Nobel in physics.

October 2024

Exit interviews with alumni retiring from Congress; the Supreme Court’s seismic shift; higher education on the ballot

September 2024

Sheikh Nawaf al-Sabah ’94 in Kuwait; Tiger Travels; Why the graduate student union vote failed.

July 2024

A Reunions to remember; 3x3 star Kareem Maddox ’11 heads to Paris; P.G. Sittenfeld ’07 has reached a verdict.

June 2024

Kahina Haynes ’11 and the problem with ballet; Andrew Golden steps down from Princo; Aaron Burr 1772’s forgotten family.

May 2024

The senior thesis at 100; attorney Brittany Sanders Robb ’13

April 2024

The art of Mary Weatherford ’84; The alumni interview endures

March 2024

The Food Issue: Hoagie Haven, Conte’s, coffee culture, a berry boss

February 2024

Lives Lived & Lost; Managing chronic pain through surfing

January 2024

Mellody Hobson ’91 and John W. Rogers Jr. ’80 fight for diversity in finance; Students talk mental health; Cornel West *80 election fears

2023

December 2023

The Legacy of Legacy; War & Words; Ross Tucker ’01 Is Going Places

November 2023

Brooke Shields ’87, Teaching organic chemistry; James Tralie ’19 at NASA

October 2023

Antiquities dealer Edoardo Alamagià ’73, Colorado Gov. Jared Polis ’96, Affirmative reaction

September 2023

Gen. Mark Milley ’80 retires as chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; A music career interrupted; ‘Trump Attorney 1’

July 2023

Rockin’ 2023 Reunions; What the Civil War cost Princeton; Addressing sustainability

June 2023

The women of ’73, Annual giving, A former Marine graduates.

May 2023

President Christopher Eisgruber ’83 on a decade of change; A basketball journey; Rabbi Gil Steinlauf ’91

April 2023

The Climate Issue; From Princeton to Policymakers; Tigers in the NCAA

March 2023

ChatGPT changes higher education; Toni Morrison exhibit; New provost Jennifer Rexford ’91.

February 2023

Lives Lived & Lost in 2022; Scholars from Ukraine and Russia; Why college rankings matter

January 2023

Crashing the conservative party; The future of fish; 100 years of Baker Rink

2022

December 2022

Attorney Alinor Sterling ’89; Organic chemistry and Maitland Jones Jr.; Renaming buildings

November 2022

Walter Kirn ’83 takes a road trip; Princeton drops fossil fuels; Coach Jesse Marsch ’96

October 2022

Dan Porter ’88 transforms sports; Adlai Stevenson 1922’s impact; The truth about dog years.

September 2022

Princeton astronomers look to Webb telescope; The doctor is on; Protecting Prospect Avenue

July 2022

Reunions 2022; Commencement times two; Alumni role: Has it changed?

June 2022

Ethics in the lab; Experiments in economics; Transfer program grows.

May 2022

Former ambassador to Ukraine Marie Yovanovitch ’80; The secret life of Jeffrey Schevitz ’62; Campus construction boom

April 2022

Following the data; A new Princeton Companion; the Ukrainian Philharmonic’s conductor

March 2022

How students with disabilities view Princeton’s campus; COVID lessons, Goin’ back for Alumni Day.

February 2022

Lives Lived and Lost 2021; The art of living; Mental health

January 2022

The philosopher musician; A new take on boarding school; Victory bonfire!

2021

December 2021

Two Texas mayors; Capitalizing racial identities; Endowment grows.

November 2021

A Ritchie Boy; Banner year for Princeton Nobels; Alumni reflect on Afghanistan

October 2021

Reckoning with the ancients; Haunted Princeton; A joyful return for students

September 2021

South African historian Jacob Dlamini, Author Michael Lewis ’82, Students return to campus

July 2021

A Commencement to celebrate; Return of the V-rade, Higher ed after COVID

June 2021

Return of the cicadas, Tiger wineries, A toolmaker’s mind

May 2021

Einstein at Princeton, A conversation with James Baker III ’52, How Lacy Crawford ’96 found her voice

April 2021

Frank von Hippel works to prevent nuclear disaster; Why we need civics

March 2021

Black and White and the Blues; Lincoln scholar Allen Guelzo

February 2021

Lives Lived and Lost, 2020; Students return; COVID-risk tool

January 2021

When song is silenced; facing failure; a refugee’s lessons

Looking for issues before 2006?

You can explore all issues prior to 2006 for free on Google Books:

The Magazine

Newsletters.

Get More From PAW In Your Inbox.