Nostalgia creeps in after 25 years. It happened to Edmund Wilson 1916; he wistfully recalled college days with Scott Fitzgerald ’17, whose eyes were “struck dark” before he reached his 25th reunion — his pen stilled by death. Wilson sighed to remember his once-happy friend “in a Princeton spring — how dimmed / By this damned quarter-century and more!”

Now it is Eighty-Eight’s turn to remember. One April night, my friend Julia invited me to a Women’s Center protest march down Prospect Avenue by candlelight:

Backlit students hung out of the windows of T. I., or gathered in bands around the front gates of Ivy, watching, murmuring, nobody daring to shout the obscenities they shouted last week when only a hundred women marched by, or to drop their pants like they did at Dial. Julia said it was the closest she’d ever felt to the Princeton community at large. I felt it, too. Here were so many of my friends, together in this worm-like column of humanity, along the rain-wetted street under the lamps and by the tiny light of the candles, and in the abrupt glare of the video-camera searchlight.

That little mid-’80s episode, as described in my yellowing coil-bound diary (U-Store, $1.39), suggests the political tensions we lived with. Feminists stressed the right of women to be on a campus from which they had been excluded for 223 years, then allowed for 15. Above all, we were to call them “women” — never, ever “girls.” And we banished “her sons” from “Old Nassau.” There were, however, far more sons than daughters: To the general misery of the former, Eighty-Eight had 725 men and only 427 women.

The ’70s had loosened mores, which had the effect of dividing us into camps — some permissive, some still stuck in the Eisenhower era. There was much fun: A contemporary survey showed 42 percent of us using drugs and 94 percent drinking. My grizzled English professor had survived kamikaze pilots and, later, rioting hippies in New Haven; in his autobiography, he singled out my generation for its frivolous disinterest in Shakespeare.

Today, nearly 6,000 full-time University employees capably erect a rational structure around adolescent lives. But if I remember it correctly, we were far less supervised. I see in my diary:

I went home to bed, on the sofa, and Danielle woke me at 1: 30 to say she hadn’t “done it,” but all the other girls had, even the “conservative” Laurie. Poor Danielle. She sat beside me in the half-darkness and communicated all her regrets at being somehow unable to strip naked and romp in the snow with a hundred leering Tiger Inn guys.

That was, of course, the Nude Olympics, one of those now-extinct indexes of how much freedom we had back then — freedom to be sophomoric. Symbolically, nothing was locked, and we clambered onto Guyot Hall’s rooftop to look at the stars. Then came fatal accidents, and 9/11, and now everything is locked.

But for us, the wide-open campus was a point of pride. Seemingly ancient alumni suddenly would appear in your dorm room, asking to see where they had lived 25 years before. Such total access helped you, in today’s parlance, be “connected to your social network,” which back then required trudging across the campus in Adidas to scrawl a note on a friend’s door at Princeton Inn College, rechristened Forbes.

My journal astounds me by showing that, when I quixotically organized an art show on that campus of engineers, I laboriously typed a letter to 35 undergraduates, licked 35 envelopes, applied 35 stamps. When I eventually got an Apple Macintosh, I wondered exactly what one ought to do with the thing and marveled to my diary: “I’m writing into the computer.” I carefully draped my Mac in a protective blanket every night, lest dust ruin its fantastically valuable innards.

None of us understood what an earthquake eventually would emanate from the article in The Prince reporting the University’s obscure plan to link campus mainframes into something “called Internet.” It might be dangerous, the reporter cautioned: “The government has said that scientists from Soviet-bloc countries should not be permitted to use the computers.”

Nor did I guess that the kid at the other table at Quad Club, Jeff Bezos ’86, would strive someday to supplant Gutenberg’s inked page with a portable electronic screen holding “every book ever printed” — Amazon’s Kindle. We did not predict that Third World Center board member Michelle Robinson ’85, who wrote in her senior thesis that she felt “like a visitor on campus; as if I really don’t belong,” eventually would command worldwide awe as a resident of the White House.

As that device “called Internet” reshapes the planet, I’ll bet our grandkids come to romanticize the old analog world, where you had to cobble things together by hand. The September we arrived in an Orwellian 1984, a campus scientist won an Emmy for making the mushroom cloud in the ABC television shocker The Day After — not with computer graphics, but by squirting dye in a water tank.

Recently Mudd Library put online a time capsule called the Class of 1986 Video Yearbook. I think our era will not be remembered for its elegance: short-shorts and tube socks and bug-eyed glasses ... sloppily facetious arch singing ... blow pong at Cottage. Time has canceled out our artless attire, and our typewriters, and even our language: Current students assure me that such favorite ’80s expressions as “bag it,” “brown-noser,” “gut course,” and “dweeb” are gone with the dodo and Devo. And a young friend tells me, “‘Girls’ is definitely the go-to word today. Not ‘women’ — that sounds almost condescending or ironic somehow.”

Back when ’70s-style feminism seemed as eternal a fact as the Soviet Threat, to say “girls” would have provoked a protest march. Such a change seems inconceivable to me — except that our Princeton spring has now been “dimmed / By this damned quarter century and more!”

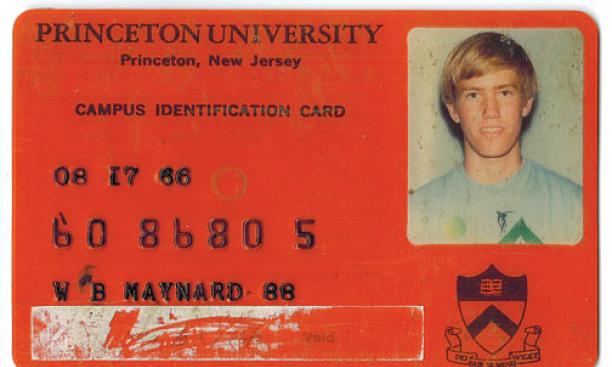

W. Barksdale Maynard ’88 is the author of Woodrow Wilson: Princeton to the Presidency (Yale University Press) and Princeton: America’s Campus (Penn State Press), published in 2012.