“Reading is a means of thinking with another person’s mind; it forces you to stretch your own. ... For learning purposes there is no substitute for one human mind meeting another on the page of a well-written book.” I found this quote of my late Dad’s via Google. (I never write about our most famous authors without consulting first with him.)

Born in 1896 on the brink of a new century, Fitzgerald’s life and career would alternate between success and setbacks like the alternating current of major and minor keys in a Mozart symphony. Just as his life bridged two centuries, so his work has a Janus-like aspect, looking back to the romantic lyricism and expansive dreams of 19th-century America, and forward to the syncopated Jazz strains of the 20th. “My whole theory of writing,” he said, “I can sum up in one sentence. An author ought to write for the youth of his own generation, the critics of the next, and the schoolmasters of ever afterward.” How magnificently — if posthumously — he fulfilled that ideal. His fleeting literary fortunes — a dozen years of commercial and literary success followed by distractions and disappointments — ended in 1940 with a fatal heart attack at the age of 44. He was then hard at work on the Hollywood novel he hoped would restore his reputation. At the time of his death his books were not, as is so often claimed, out of print with Scribner, his publisher. The truth is even sadder: They were all in stock at our warehouse and listed in our catalogue; but no one was buying them. When his daughter, Scottie, first approached the Princeton University Library and offered to give them her father’s papers she was turned down. They couldn’t be the repository, someone said, for every failed alumnus author’s papers. Fortunately she gave them a second chance, years later, to reconsider, and today those archives are the most avidly consulted holdings of the library, by scholars who come there, as if on pilgrimage, from all over the world.

A half-century later, more copies of Fitzgerald’s books are sold each month than the entire cumulative sale throughout his lifetime. His novels and stories are studied in virtually every high school and college across the country. I am the fourth Charles Scribner to be involved in publishing his works since my great-grandfather first signed him up, at the prodding of Max Perkins, in 1919. My grandfather, Fitzgerald’s contemporary and friend as well as publisher, died on the eve of the critical reappraisal and the ensuing revival of his works that gained momentum in the 1950s and has continued in full force down to the present time. It was my father who presided over a literary apotheosis unprecedented in modern American letters. I am struck by the realization that I am the first generation — of no doubt as many to come — to have been introduced to this author’s work in a classroom.

As a fledgling editor, I had the good fortune to work closely with Fitzgerald’s talented and delightful daughter, Scottie, together with her dedicated adviser Matthew J. Bruccoli, whose prolific scholarship and infectious enthusiasm have long fanned the flames of Fitzgerald studies. The day I met Matt, four decades and many books ago, I asked him what had prompted him to devote the lion’s share of his scholarly life to Fitzgerald. He told me exactly how it happened.

One Sunday afternoon in 1949 Bruccoli, then a high-school student, was driving with his family along the Merritt Parkway from Connecticut to New York City when he heard a dramatization of The Diamond as Big as the Ritz on the car radio. He later went to a library to find the story; the librarian had never heard of F. Scott Fitzgerald. But finally he managed to locate a copy — “and I never stopped reading Fitzgerald,” he added. This story struck a familiar chord — for I too remember where I was when I first encountered that same literary jewel “as big as the Ritz.”

It was an evening train ride from Princeton to Philadelphia: A commute was converted into a fantastic voyage. Fitzgerald later converted my professional life just as profoundly, claiming more of me than any living author. There are worse fates in publishing than to be “curator of literary classics,” especially if one’s own scholarly training is in Baroque art. Placed aside my other specialties, Rubens and Bernini, Fitzgerald seems very young indeed: a newcomer in the pantheon of creative genius.

There is something magical about Fitzgerald. Much has been written — and dramatized — about the Jazz-Age personas of Scott and Zelda. But the real magic lies embedded in his prose, and reveals itself in his amazing range and versatility. Each novel or story partakes of its creator’s poetic imagination, his dramatic vision, his painstaking (if virtuoso and seemingly effortless) craftsmanship. Each bears Fitzgerald’s hallmark, the indelible stamp of grace. He is my literary candidate to stand beside the demigods Bernini, Rubens, and Mozart as artists of divine transfigurations. The key to Fitzgerald’s enduring enchantment lies, I submit, in the power of his romantic imagination to transfigure his characters and settings — as well as the very shape and sound of his prose. There is a sacramental quality — one that did not wane along with the formal observance of his Roman Catholic faith. I say “sacramental” because Fitzgerald’s words transform their external geography as thoroughly as the realm within. The ultimate effect, once the initial reverberations of imagery and language have subsided, transcends the bounds of fiction. I can testify from firsthand experience.

When I arrived at Princeton as a freshman in the fall of 1969, I was following the footsteps of four generations of namesakes before me. Yet, surprisingly, I did not feel at home. It seemed a big impersonal place: more than 10 times as big as my old boarding school, St. Paul’s. There I had first been exposed to Fitzgerald in English class, where we studied The Great Gatsby. But my first encounter at Princeton was dramatically extracurricular. One day that fall, soon after the Vietnam Moratorium and the ensuing campus turmoil, I returned to my dormitory room to find that some anonymous wit had taped to my door that infamous paragraph from Fitzgerald’s The Rich Boy: “Let me tell you about the very rich. They are different from you and me.” (My next-door neighbors in the dorm represented a cross section of campus radicals; and while I was hardly “very rich” by Fitzgerald’s lights — closer to Nick Caraway than to the Buchanans — I was still the son of a University trustee.) Stung as I was by this welcome note, curiosity got the better of me. So off I went to Firestone Library, looked up the story, and read it.

Now hooked by Fitzgerald, I bought a copy of This Side of Paradise, his youthful ode to Princeton. Though University officials to this day bemoan its satirical depiction of their college as a country club (if there was any book they could ban, this would be it), they miss the point — the poetry, the sacramental effect of this early, flawed novel on their majestic campus. For me, this book infused the greenery and gothic spires with a spirit, with a soul, with life. Fitzgerald transfigured Princeton. I now saw it not as a stranger, but through the wondering eyes of freshman Amory Blaine:

Princeton of the daytime filtered slowly into his consciousness—West and Reunion, redolent of the sixties, Seventy-nine Hall, brick-red and arrogant, Upper and Lower Pyne, aristocratic Elizabethan ladies not quite content to live

among shop-keepers, and topping all, climbing with clear blue aspiration, the great dreaming spires of Holder and Cleveland towers. From the first, he loved Princeton—its lazy beauty, its half-grasped significance, the wild moonlight revel of the rushes.

For me it was not love at first sight; but thanks to Fitzgerald, it was love at first reading. Oscar Wilde was right: Life imitates art, not the other way around. We view our world through a prism of words. During my sojourn there, my friends and I would religiously recite Fitzgerald’s sonnet of farewell to Princeton: “The last light fades and drifts across the land — the low, long land, the sunny land of spires...”

From his earliest days, Scott wanted nothing more than to be a writer: “The first help I ever had in writing was from my father who read an utterly imitative Sherlock Holmes story of mine and pretended to like it.” It was his first appearance in print, at age 13. Here’s the chilling denouement (which proves we can all write as well as Fitzgerald):

“I forgot Mrs. Raymond,” screamed Syrel, “Where is she?” “She is out of your power forever,” said the young man. Syrel brushed past him and, with Smidy and I following,

burst open the door of the room at the head of the stairs. We rushed in. On the floor lay a woman, and as soon as I touched her heart I knew she was beyond the doctor’s skill.

“She has taken poison,” I said. Syrel looked around; the young man had gone. And we stood there aghast in the presence of death.

No surprise that he next took to writing plays, one a summer, for a local dramatics group. At Princeton, he wrote musical comedies for the Triangle Club before he flunked out (chemistry was the culprit), joined the army, and wrote his first novel, This Side of Paradise, which debuted in 2005 as a musical in the East Village under a new title: The Pursuit of Persephone.

“Start out with an individual and you find that you have created a type — start out with a type and you find that you have created nothing.” Fitzgerald started out with himself — a good choice. “A writer wastes nothing,” he said — and he proved it by mining his early years at St. Paul, Minn. and Princeton to forge his early stories, poems, and dramatic skits into that witty autobiographical novel that launched his fame.

Fitzgerald’s first novel was turned down — can you believe — twice by my great-grandfather, until after several revisions by a young writer who refused to give up, it was published to great acclaim. Years later, writing to his daughter, Fitzgerald offered the following advice: “Don’t be a bit discouraged about your story not being tops ... Nobody became a writer just by wanting to be one. If you have anything to say, anything you feel nobody has ever said before, you have got to feel it so desperately that you will find some way to say it that nobody has ever found before...”

A couple years later, he added some more technical advice: “About adjectives: All fine prose is based on the verbs carrying the sentences. They make sentences move.”

Unlike Scott’s brisk prose, I did not move; I stayed on at Princeton for two more graduations, leaving the University only when there were no more degrees to be had, but not before I had the pleasure of teaching undergraduates. Since my field was art history, the next transition into the family publishing business was abrupt, but once again facilitated by Fitzgerald. Ensconced at Max Perkins’s old desk at Scribner (which I was given because the senior editor complained that it ran her stockings!), I dreamed up as my first book project in 1975, a revival of Fitzgerald’s obscure and star-crossed play The Vegetable, which featured a presidential impeachment too true to be good: Can you believe the play had opened — and closed — in 1922 at Nixon’s Apollo Theatre in Atlantic City? My post-Watergate project not only justified repeated revisits to the Princeton University Library for research in the Scribner and Fitzgerald archives — the Mecca for Fitzgerald scholars — but, more important, it brought me into a happy working relationship with Scottie. It was published during the election year of 1976, and since we find ourselves again in the dusty deritus of election politics, I’d like to recommend Fitzgerald’s version of a presidential address. (Perhaps some might picture a present candidate as the speaker?) Fitzgerald whips up a delicious confection of mixed metaphors.

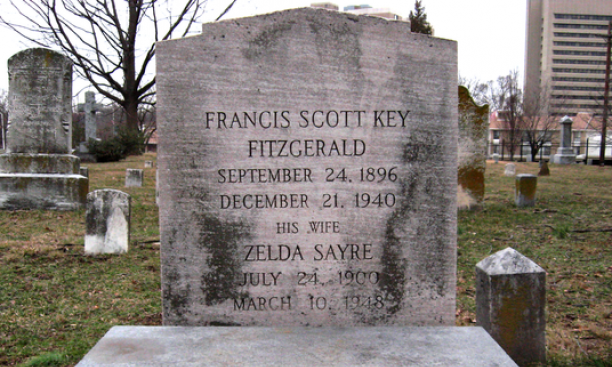

After approving my introduction to the play, Scottie wrote me a touching note about her parents’ reburial service in the Catholic cemetery of Rockville, Md. I had been unable to attend, and instead had arranged for a memorial mass to be said that day in the once exclusively Protestant Princeton chapel. No doubt Fitzgerald smiled at the delicious irony of both liturgies. “Surely it was the Princeton prayers,” Scottie later wrote to me, “which made our little ceremony go so smoothly. The day was perfect; a mild breeze rustling the fallen leaves, and there were just the right number of people, about 25 friends and relatives, 25 press, 25 county and church ‘officials,’ and 25 admirers who just popped up from nowhere. As most of the guests had never before had bloody marys in a church basement, the party afterward was a jolly affair, too. I’m sorry you weren’t there, but loved knowing we were having a backup ceremony in his real spiritual home.”

I cannot resist contrasting Scottie’s gracious note with what Edmund Wilson 1916 wrote to me when I had first proposed that he reintroduce the play Fitzgerald had dedicated to him. Wilson had given its publication a rave newspaper review — a fact he now conveniently chose to forget: “I cannot write an introduction to The Vegetable. The version I read and praised was something entirely different from the version he afterwards published, and I did not approve of this version. The trouble was he took too much advice and ruined the whole thing. I was not, by the way, as you say, closer to Fitzgerald than anybody else. I was not even in his class at college, though people still think and write as if I had been...”

When I lamented this letter to my father, he said that for Wilson it wasn’t so bad, jesting that “after God created the rattle snake, he created Edmund Wilson.” Not long afterward, I unwittingly allowed Wilson’s first name to be misspelled “Edmond” in huge letters on the cover of our paperback edition of Axel’s Castle. My Freudian slip is now a collector’s item, which fortunately for me, Edmund did not live to see!

Fitzgerald considered his year and a half spent on The Vegetable a complete waste, but I disagree. For he followed it with a new novel, written with all the economy and tight structure of a successful play — The Great Gatsby. Both The Vegetable and Gatsby shared the theme of the American Dream (first as a spoof for a comedy, finally as the leitmotif of a lyric novel).

I don’t think there has ever been a more elusive, mysterious, intriguing character than Gatsby. He’s pure fiction — and pure Fitzgerald: the hopeful, romantic outsider looking in.

He smiled understandingly — much more than understandingly. It was one of those rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it that you may come across four or five times in life. It faced — or seemed to face — the whole external world for an instant, and then concentrated on you with an irresistible prejudice in your favor. It understood you just so far as you wanted to be understood, believed in you as you would like to believe in yourself and assured you that it had precisely the impression of you that, at your best, you hoped to convey.

Who cares how James Gatz became Jay Gatsby — bootlegger, or worse? Who would not want to be in such a presence, and call him friend? But it was years later — when I first met Bill Clinton through my Princeton classmate and friend Queen Noor of Jordan — that those sentences came to life and recorded my experience of mortal, if presidential, charisma I could never have imagined outside the bounds of fiction. Clinton made Gatsby real; or perhaps Gatsby prefigured Clinton?

Fitzgerald wanted his book to be a “consciously artistic achievement ... I want to write something new — something extraordinary and beautiful and simple and intricately patterned.” And he succeeded in spades. He later said that what he cut out of it, “both physically and emotionally, would make another novel.”

In his first letter to Perkins — summer of 1922 — about his “new” novel, Fitzgerald wrote that it would “concern less superlative beauties than I run to usually,” and “would center on a smaller period of time.” He was to change the period and locale as he began writing (it was originally set in the Midwest and New York around 1885), but he never abandoned his determination to limit the time frame and thus give a sharper focus to his plot and characters than he had done in his earlier two novels. And this, I think, was the result of his failed attempt to be a Broadway playwright. The special demands imposed by a play — a short work defined by acts and scenes, limited in time and setting — proved an ideal exercise in literary craftsmanship, which the young novelist sharpened through the long series of revisions while the play was in rehearsal.

From Fitzgerald’s long-lost first draft of 1923, only a fragment survives in the form of the short story “Absolution” and two handwritten pages I discovered 30 years ago in a rare book shop here in New York: They reveal that Fitzgerald had already settled on the essential plot and locale of the final version, but the story was told in the third person. The next year he wrote to Perkins that he was now working on a “new angle” — I’m sure he meant through the eyes of his inspired narrator Nick Carraway. (It’s worth renting the video of the famous Redford film just to hear Sam Watterson tell the story — 36 years before the final episodes of Law & Order!)

In the flush of creativity, Fitzgerald wrote to his editor: “I feel I have enormous power in me now, more than I’ve ever had in a way, but it works so fitfully and with so many bogeys because I’ve talked so much and not lived enough within myself to develop the necessary self-reliance. Also I don’t know anyone who has used up so much personal experience as I have at 27.” Perkins, for his part, had grave reservations about the proposed title, Among the Ash Heaps and Millionaires, and suggested that Fitzgerald return to The Great Gatsby, which he called effective and suggestive. He also commissioned at this early date — seven months before the author completed his manuscript — the most famous jacket painting of the past century, which we’ll consider as bit later. He continued to revise his draft from September to October, “working at high pressure to finish,” he wrote in his ledger. In November 1924, he mailed the manuscript to Perkins with a new title, Trimalchio in West Egg. He was to run through several others — Trimalchio, Gold-Hatted Gatsby, Gatsby, The High-Bouncing Lover, and On the Road to West Egg — before Perkins’ steady favorite was restored in time for publication. Most of the final revising was done directly on the printed galley proofs, which Fitzgerald treated almost as a clean typescript. (In fact the uncorrected galleys, titled Trimalchio, were published a decade ago, as if a distinct novel.) Then, just three weeks before publication on April 10, 1925, the nervous author cabled his editor from Paris: “Crazy about title Under the Red, White, and Blue.” But fortunately it was too late to change the title and our book was spared the fate of sounding like a George M. Cohan song.

While writing an introduction to a new paperback edition of Gatsby, I decided to revive the original jacket, which is now an icon of the Jazz Age, and was most recently enlarged as a huge poster for Harbison’s opera at the Met. When Matthew Bruccoli discovered Cugat’s preliminary sketches for the Gatsby dust jacket in a country shop, serendipity allowed me at last to merge art history and literature. I’m a Gemini. For this once, thanks to Fitzgerald, my dual careers came into sync.

Francis Cugat’s painting is the most celebrated and widely disseminated jacket art in 20th-century American literature, and perhaps of all time. After decades of oblivion, and several million copies later, like the novel it embellishes, this Art Deco tour de force has established itself as a classic of graphic art. At the same time, it represents a unique form of “collaboration” between author and jacket artist. Under normal circumstances, the artist illustrates a scene or motif conceived by the author; he lifts, as it were, his image from a page of the book. In this instance, however, the artist’s image preceded the finished manuscript and Fitzgerald actually maintained that he had “written it into” his book.

Cugat’s small masterpiece is not illustrative, but symbolic, even iconic: The sad, hypnotic, heavily outlined eyes of a woman beam like headlights through a cobalt night sky. Below, on earth, brightly colored lights blaze before a metropolitan skyline. Cugat’s carnival imagery is especially intriguing in view of Fitzgerald’s pervasive use of light motifs throughout his novel; specifically, in metaphors for the latter-day Trimalchio, whose parties were illuminated by “enough colored lights to make a Christmas tree of Gatsby’s enormous garden.” Nick sees “the whole corner of the peninsula ... blazing with light” from Gatsby’s house “lit from tower to cellar.” When he tells Gatsby that his place “looks like the World’s Fair,” Gatsby proposes that they “go to Coney Island.” Fitzgerald had already introduced this symbolism in his story Absolution, originally intended as a prologue to the novel. At the end of the story, a priest encourages the boy who eventually developed into Jay Gatsby to go see an amusement park—“a thing like a fair only much more glittering” with “a big wheel made of lights turning in the air.” But, “don’t get too close,” he cautions, “because if you do you’ll only feel the heat and the sweat and the life.”

Daisy’s face, says Nick, was “sad and lovely with bright things in it, bright eyes and a bright passionate mouth.” In Cugat’s final painting, her celestial eyes enclose reclining nudes and her streaming tear is green — like the light “that burns all night” at the end of her dock, reflected in the water of the Sound that separates her from Gatsby. What Fitzgerald drew directly from Cugat’s art and “wrote into” the novel must ultimately remain an open question.

The multicolored lights of Gatsby — whether votive or festive — seem a suitable image for a Fitzgerald banquet on Gatsby’s Island, where my family and I were transplanted 28 years ago after several generations on the other side of the Hudson River. From our new vantage point, I cannot look out over the Sound, as I do each week, without smiling at Fitzgerald’s description: “The most domesticated body of salt water in the western hemisphere, the great wet barnyard of Long Island Sound.” There is no longer a dock at the beach in Lattingtown, and, as the crow flies, we are in fact several miles east of East Egg. But occasionally I catch a glimpse of a green light reflected in the water, and each time I drive through the Valley of Ashes and approach the twinkling Manhattan skyline, I feel very much at home. The novel has made me a native.

One wise teacher once told me that the ultimat e function of art is to reconcile us to life. Fitzgerald’s prose is life-enhancing; its evocative power endures. That is why I have no doubt he must be beaming — from the other side of Paradise.