When Yasser El Halaby ’06 arrived at Princeton in the fall of 2002, he was too late for freshman orientation and already had missed several of his classes, his departure from Egypt stalled by post-9/11 student-visa delays. To help him get settled, El Halaby’s squash coach, Bob Callahan ’77, accompanied him to the first meeting of each of his classes, personally introducing him to each professor. It was a small gesture, but a memorable one.

El Halaby went on to win four individual national titles and become one of the greatest players in collegiate men’s squash history. Of his coach, El Halaby says, “He was more supportive off the court than on.”

Callahan, who retired in April after 32 seasons at Princeton, had remarkable on-court success, winning three national championships and 11 Ivy League titles. He might have added more wins to his record if not for a bout with brain cancer that took a toll on his energy in the last year. But when players talk about the coach, they rarely begin with the winning. They’re more likely to mention how friendly and welcoming he is, or how he spoke effusively about rival teams during pre-match introductions.

Recent players like El Halaby see Callahan as a paternal figure — not surprising, since he had five sons who played for Princeton between 2001 and 2011. At the beginning of his career, though, the coach was just a few years older than the players he was coaching. According to Rob Hill ’84, a former team captain, those early teams were stocked with “a bunch of cowboys” — talented free spirits who needed guidance — and Callahan managed to corral the group, not by imposing some strict code of discipline but by working to help each individual improve.

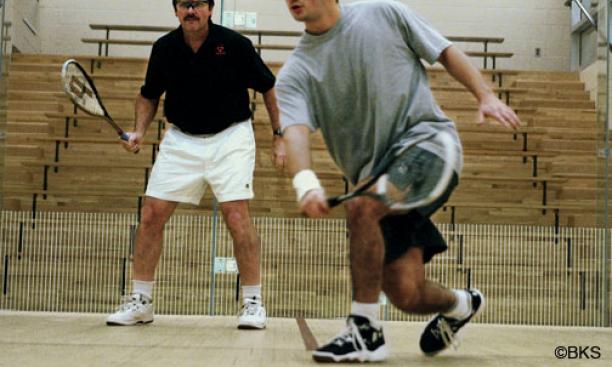

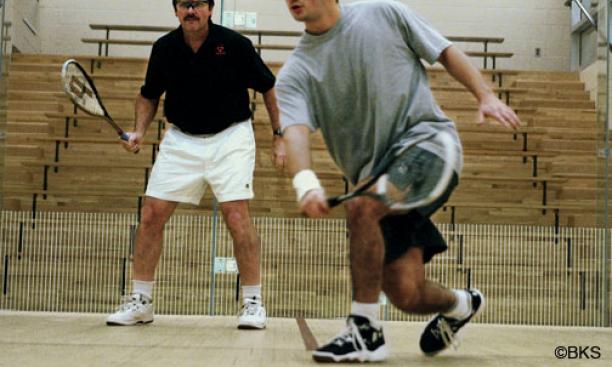

Callahan also preached sportsmanship. Squash is contested in close quarters, with players essentially refereeing their own matches. It’s relatively easy to aggravate an opponent by, for instance, hesitating to clear the space he needs to play a shot. Coaches can see that type of behavior, and Callahan was quick to correct it. “He taught people how to play the right way, and that’s really a critical thing,” Hill says.

Neil Pomphrey, the Tigers’ assistant coach for the last 21 seasons, says that the soft-spoken Callahan had his fiery, motivational moments, but they were reserved for “the right time, and for the right reasons.” When Callahan’s nerves began to show during tense matches, he would retreat to spots shielded from the court to avoid distracting his players.

The image of a nervous Callahan slipping behind a pillar may seem quaint to sports fans more accustomed to watching coaches who stalk the sidelines and scream at players. But it’s useful to know that there’s more than one way to be a winner. You can be gentle and respectful and compete for national championships.

Sometimes, the nice guy finishes first.

Brett Tomlinson is PAW’s digital editor and writes frequently about sports.