In Old Trenton, the historic district just east of downtown, redbrick row houses are crumbling, their windows broken, their upper rooms open to the sky. A banner flaps across one drooping façade, advertising new apartments “coming soon” — in 2009. The streets are mostly empty, the klatches of men who stood outside the barred Hi-Grade Wine & Liquor store now dispersed by an approaching storm. But on Wood Street, a narrow lane gouged with potholes, lights are burning inside a squat former print shop where Isles, a local nonprofit, salvages Trenton’s remains: repurposing scrap tires as planters for a vegetable garden and boarded-up windows as vibrant murals. To Isles, blight is just another kind of opportunity.

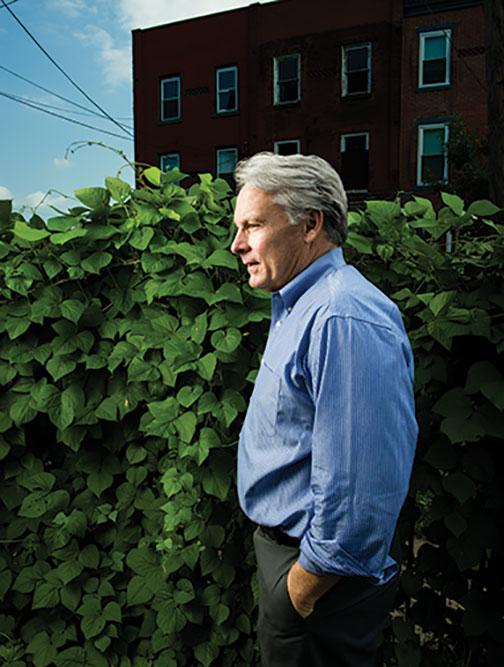

Marty Johnson ’81, founding president of Isles, possesses a keen sense of what lies beneath the decay. “Marty can see something no one else can see,” says Isles training manager Andre Thomas, who joined the organization after serving five years in prison. For more than three decades, Johnson has worked to reclaim Trenton from the creep of urban decline. Gordon MacInnes *65, a two-term New Jersey state senator who now heads the nonprofit research institute New Jersey Policy Perspective, admires Johnson for creating a successful social enterprise in a city with “very little civic life left.”

A think-and-do-tank with a $9.57 million budget and an up-by-the-bootstraps mantra, Isles helps the poor to help themselves. Its community-development projects work to revitalize neighborhoods, “physically rebuilding out of the existing stock of Trenton,” says Alejandro Zaera-Polo, dean of Princeton’s architecture school. On nearby Tucker Street, a 20,000-square-foot former paint factory has been revamped (with a $1 million donation from NRG Energy, headed by Johnson’s classmate David Crane) into a solar-powered alternative high school and solar-vocational training center. Isles Youth Institute has helped about 650 high school dropouts earn a diploma or GED certificate and prepared about 870 unemployed people for energy-industry jobs. An Isles weatherization and home-safety subsidiary called E4, which employs some of those trainees, has tested for lead in about 2,100 homes and removed lead from dozens. Isles also establishes and manages community gardens, provides financial counseling and low-interest loans, and rehabilitates homes and helps low-income residents purchase them. As Johnson says, “We’re starting with people’s capabilities. We provide them with enough assistance, kick ’em in the ass, and give ’em a hug.”

Johnson is about 6 feet tall, with burly limbs that betray his days as a gunner on Princeton’s football squad. A self-described “serial entrepreneur,” Johnson draws funding from more than 300 sources. But he shifts fluidly between executive argot and street talk, and knows that some Youth Institute students think of him “like a dad.” He pays little mind to most conventional measures of success, which he finds short-term and incomplete. He appraises his work, instead, by lessons learned — “where the magic is,” he often says — and believes that the path out of poverty is a path to self-reliance, “a way not to be needed.”

Industry first came to Trenton in the late 17th century, when Mahlon Stacy, a Quaker from England, built a grist mill. For generations, the city would see itself as a center of manufacturing, notably proclaiming its status in 1935 on a bridge spanning the Delaware River — “TRENTON MAKES” emblazoned on one side, “THE WORLD TAKES” on the other — to signify the burgeoning manufacture of ceramics, cigars, and wire cables that could suspend landmark bridges. But as in other Rust Belt cities, industry in Trenton eventually ground to a halt. Today, 26.6 percent of its residents live in poverty, a rate that’s almost three times the state average. In Isles’ neighborhood of Old Trenton, within sight of the gold dome crowning the State House, poverty is even more widespread.

More than three decades after Isles began working in Trenton, poverty in the city — and increasingly, in the surrounding suburbs — only has worsened. “One of the problems of trying to assess anybody’s work in a situation like that is, how do you measure their progress against a flood tide? You’re building sand castles and you’ve got a tsunami coming,” says MacInnes. Still, Isles’ multifarious efforts in community development, public health, alternative education, and job training provide vital lifelines to families and neighborhoods, he says. “And they’re doing it against enormous negative forces that they can’t control.”

Johnson believes that federal antipoverty programs can encourage dependency. Isles receives federal and state funding for major projects, though it aims to prevent dependency by requiring participants to demonstrate initiative — for example, to pay a small fee for financial-literacy services. Isles’ philosophy begins “with an expectation that individuals want to be self-reliant, and are capable of managing their own interventions with relatively little intermediation,” he says. “Government employees, even smart ones, are not better able to manage the lives of those in poverty.”

Rutgers professor Julia Sass Rubin, a visiting professor at the Woodrow Wilson School, says beleaguered cities need “actors on the ground” who are able to monitor local conditions and mobilize swiftly. “Government is not good at adapting quickly,” she says. “And the theory is, that’s why you have community-based responses: They can be on the ground and meet the needs. What you have with Isles is just a well-managed organization that can harness the resources and meet the needs.” Yet, in Trenton, one of the poorest cities in one of the country’s wealthiest states, some needs are met only by government’s social-safety net, Rubin says. “The idea that families can just pull themselves up by their bootstraps, that you don’t need to create infrastructure and address institutional barriers and provide subsidy, is a false one,” she says. “You need to do both.”

Johnson grew up in Akron, Ohio. When he was 16, his parents divorced and lost the family house. Johnson and his younger brother and sister stayed with their mother, who was disabled from an accident and unable to work. The household survived with public assistance and help from others. When Johnson would buy groceries with food stamps, the transactions unnerved him. He feared being stigmatized, labeled as “a kind of sick patient,” and he strained to be “treated as still capable, still normal.” Confronting scarcity, he thought only of immediate needs, and worried about being driven to make poor decisions. “To do that as a kid,” Johnson says, “that really sears into your psyche, becomes a part of who you are.”

Brought to Princeton, in part, to play football, Johnson never quite felt settled. Teammate John Kistler ’81 recalls players ribbing Johnson for wanting to save the world. An anthropology major, Johnson itched to escape academia for “real-world problem-solving,” and in the spring of his junior year, he traveled to the state of Pernambuco in northeastern Brazil. After two months of refining his Portuguese and observing local customs, he meandered south along the coast, reaching a fishing village in the Port of Suape. It was, he says, “the most beautiful place I had ever seen — ever.” But multinational corporations had proposed an industrial complex, and residents were rallying to defend their estuary and way of life. Johnson wrote his junior paper in condemnation of such projects “done in the name of progress.” Then he hitchhiked around Brazil, ruminating: “What would it look like if you really wanted to restore the environment and help those you really thought needed to be helped?”

Approaching graduation, Johnson considered job offers from corporations, including one that would have paid “more than my father ever made,” he says. He turned them down.

“We’re basically handed a sword when we leave FitzRandolph Gate,” Johnson says. “The sword cuts in two directions. The sword is basically saying you can do anything now. And the beauty is that you can do anything. The danger of that is that you can do anything. So how do you keep some level of humility, and use the good side of the sword to take some risks and go out and make change?”

Toward the end of his senior year, Johnson, along with Mark Schultz ’80, Ian Keith ’80, and Andrew Reding *77, started Isles. Schultz, now an associate director at the Land Stewardship Project in Minnesota, says that Isles was envisioned as something “that could be owned and controlled and operated by local communities, not by distant experts from afar.” After graduation, the partners shared a $100-a-month room in Trenton and a car with “holes in the floorboards,” and eked out about $10,000 to spend on projects. An early $31,000 grant from the Dodge Foundation kept Isles afloat. (“It was a slight roll of the dice,” says Scott McVay ’55, the former executive director at Dodge.)

After a few years, the partners left, and Johnson settled in for a long haul. He married Liz Lewis, a plant pathologist, and started a family. The Johnsons lived in a Trenton neighborhood by the Delaware River known as the Island. It was quieter than other parts of the city, but friends and family members still considered the move “risky and experimental,” Johnson says. They had three sons, who attended local schools — making friends and receiving reduced-price lunches like most of their peers. All three transferred to the private Princeton Day School for middle or high school, a move that made Jeremy Johnson, who later entered Princeton with the Class of 2009, aware of educational and socioeconomic disparities. “I was pretty academically behind,” he says. “I was entering a much more elite group of people who did not worry about things that I had to worry about. ... We were never hungry. But we were very conscious of the fact that we couldn’t [afford to] do things.” He adds: “There were a handful of awkward moments where parents of my friends wouldn’t let them come over to play because they didn’t want them in Trenton.”

At Isles, Marty Johnson, who has been a Princeton trustee and visiting fellow at the Woodrow Wilson School, often draws on his anthropology training, which equipped him to deal with “reasons that people give for fearing outsiders.” In a predominantly black, poorly educated community, he has had to answer for being “too white” and “too educated.” He plays down the considerable intellectual horsepower of Isles’ staff (which includes three alumni). He eschews the word “program” in describing what Isles does because he thinks it implies a “power relationship” that marginalizes the poor. Instead, he prefers “product,” which “ultimately hinges on people taking this stuff and moving toward self-reliance and away from needing you.”

The Youth Institute doors open by 7 a.m., when all 50 or so students engage in guided self-reflection, and close around 9 p.m., when anyone left behind is delivered home safely by car. Students learn by doing: To study geometry, they truss roofs; to study business, they run one. Prospective students submit to a week-long boot camp of physical tests (push-ups, sit-ups, sprints) and prohibitions (no cellphones, no gang colors). Johnson aims to weed out anyone attending only because of a guardian’s insistence or a judge’s decree. He calls it “tough love.” “When push comes to shove, we’re not interested in graduates,” he says. “What we’re interested in are people who are on the pathway to self-reliance.”

In early 2005, Johnson made one of his few exceptions and accepted a student from a judge. Donta Sanders, then 17, had been expelled from school and jailed half a dozen times for, among other charges, assault with a deadly weapon. But coming from a large family with a sick mother to care for, Sanders struck a chord with Johnson. Sanders enrolled at the Isles Youth Institute, studying construction. He took his first trip beyond Trenton (to the Wyoming Rockies), got his first suit (Calvin Klein, $350), and gave his first public speech (to more than 300 people). Johnson “pushed me outside my comfort zone and showed me what I was capable of,” he says.

Today, Sanders is still finding his way, raising his two children as a single father and earning $17.50 an hour doing maintenance for a real-estate company. He feels more capable, personally and professionally. “Before, I walked around like somebody owed me something,” he says. “Now I’m a little bit more humble, willing to hear somebody else’s problems, OK with constructive criticism. And these qualities are helping me go through life.”

Beyond working student-by-student and block-by-block, Isles is implementing a plan to spark revitalization on a wider scale. Led by Julia Taylor ’99, Isles’ managing director of community planning, Isles conducted a community-needs survey for Trenton in 2009, finding that the city’s most pressing concern was property abandonment. This spurred Isles to inventory vacant properties, identifying thousands of empty buildings and lots. To prevent the vacancy problem from expanding, Isles has counseled about 1,500 families about home ownership, helping about a third of them avoid foreclosure or move into affordable homes. Isles has “this really strong knowledge base of what people are looking for,” says Marc Leckington, Trenton’s deputy director of housing and economic development, “and this great 10,000-foot view of what’s going on in the city.”

On 1.7 acres that lay fallow for most of Isles’ existence, Roberto Clemente Park now sports a pastel-colored playground and a full-size basketball court outfitted with glinting rims and bleachers. In 10 abandoned buildings on Stockton Street, where copper piping had been stripped for scrap metal and used needles were strewn beside bare mattresses on the concrete floors, 26 spruced-up units will be offered for rent or sale later this year; in the nearby Stockton Arms complex, another 34 are being rehabilitated. Backed by state grants, Isles has developed more than 500 affordable homes.

Isles manages 60 community gardens and has established more than 150 over the years, yielding, Johnson estimates, more than a million pounds of fresh produce in communities lacking supermarkets selling healthy food. Isles construction students have built many of the raised beds — necessary to avoid poor soil — and recently created a beds-and-sheds micro-business to serve other gardeners, Johnson says.

June Ballinger, executive artistic director of Passage Theatre Co., a community arts organization, can remember looking out her office window onto “all sorts of squalor going on in the alley — people using it as a bathroom, and drinking, and prostitution,” she says. “And a lot of that has gone away.” With Passage, Isles has applied for (and matched) a $75,000 National Endowment for the Arts grant to create an arts district near the Trenton Transit Center.

Isles has had disappointments, as well. In 2008, Isles partnered with state police to launch Operation CeaseFire, which deployed civilian volunteers to connect crime victims to social services and to defuse tension between gang members. Trenton police statistics suggested that the program reduced gun-related crime, but after two years, funding ran out and violence escalated.

“There have been lots of moments when I thought it made no sense to continue to do this, and lots of good reasons why I should have left,” Johnson says. “But they weren’t good enough to overcome what was a basic belief that we had to get through the hardest times, had to get through the burnout, in order to find out what’s real and what’s possible.”

Recently, Johnson noticed a curious trend: Most of those approaching Isles for housing assistance have been looking beyond the city, not within it. Johnson saw that Trenton was losing population, while the surrounding suburbs were gaining. At the same time, poverty metrics — students eligible for free lunches, median household income, private jobs — showed that Trenton’s problems had bled into the communities around it. “It started as just Trenton,” Johnson says. “Now it’s moving.” He compares Isles’ anti-poverty efforts to “running up an escalator.”

Early next year, Isles will move into a sprawling, late-19th-century former textile mill in Hamilton, just outside of Trenton, as part of a larger project to create a “sustainable urban village” called Mill One with mixed-income housing, a business incubator, an artist residency, and a hub for nonprofits. Athletes and alumni members of the Princeton Varsity Club have helped demolish parts of the old building and assisted in landscaping, painting, and cleanup. Students in a University class on sustainable design helped Isles evaluate options such as geothermal energy and rainwater recapture; another class explored weatherization techniques. Once completed, about four years from now, the $20 million complex will enable Isles to continue its work in Trenton while expanding beyond. “This building enables us to regionalize our services in a way that makes more sense, and really does honor what’s happening now, which is that [poverty is] not just a city issue anymore,” Johnson says.

In a recent letter to his sons, Johnson reflected on raising them in Trenton and including them in activities at Isles. The three boys were shuttled around to community-organizing events; they discussed social issues over dinner and did homework at Isles. “We had created an organization that was a labor of love — our chance to improve the world and be creative,” Johnson wrote. “Isles gave us a chance to get to know Trenton and its people as a bundle of assets, not just deficits (or sick systems) to overcome. ... In our ideal world, our kids would deeply experience both Princeton and Trenton, function highly in each, and even be a bridge between them.”

Today, son Lon Johnson ’08 is a lawyer; Colin ’13 works in marketing. Jeremy Johnson left Princeton after his junior year in 2006 to run a business he had founded as a student. Since then, he co-founded the online-education company 2U, which went public in March. He also joined the board of PENCIL Inc., a New York partnership between businesses and schools. His interest in education, he says, stems from his “direct experience with the Trenton public school system and with friends left without any college guidance.” Noting the “extraordinary” guidance he received in his private school, he is trying, as his father had hoped, to connect his two worlds.

Jeremy draws inspiration from his father’s sheer doggedness and commitment. Most people trying to do good for a neglected community on a shoestring budget would have failed, Jeremy believes, but his father “was unwilling to fail — through his stubbornness and ingenuity and unwillingness to let this problem go.” Then, he adds: “He’d like nothing more than to make Isles irrelevant.”

Dorian Rolston ’10 is a freelance writer living in Cambridge, England.