One sunny day last August, Principal Chief Bill John Baker gave the annual State of the Nation address on the Cherokee Courthouse lawn in Tahlequah, Okla. He began with a reference to what he called one of America’s worst tragedies — the Trail of Tears, in which Southeastern American Indians were removed by U.S. troops at gunpoint.

“It was 175 years ago we arrived here in eastern Oklahoma and began our greatest chapter, building the largest, most advanced tribal government in the United States,” Baker said. “Our ancestors were pulled from their homes in the East, forced into stockades, and marched here to Indian Territory by a federal government that tried to brutally extinguish us. But in 1839, right here in Tahlequah, we reconstituted our government ... and re-created the commercial success we had in the Southeast.”

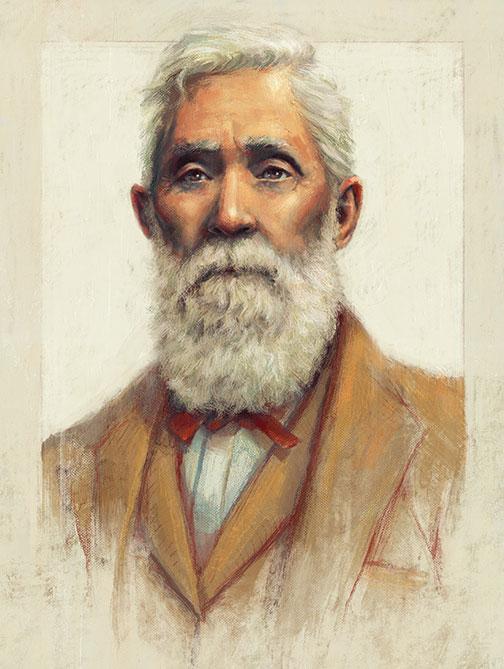

The Cherokee Nation survived and even prospered. A key figure in that story was Chief William Potter Ross 1842, one of the few Native Americans to attend Princeton in the 19th century and the first to graduate. Ross’ portrait hangs in the Cherokee Nation Tribal Complex in Tahlequah today, where he is remembered for helping to heal schisms within the tribe and fighting tirelessly for the right of the Cherokee to govern themselves — a right not finally guaranteed until the 1970s.

“Ross argued for an arena of autonomy for Indian people within the United States,” says Frederick E. Hoxie, professor of history and American Indian studies at the University of Illinois. “He was a very sophisticated thinker and a man far ahead of his time.”

By 1820, the year Ross was born near Chattanooga, Tenn., the Cherokee of the Southeast had interacted with Anglo-Americans for generations, and intermarriage was common. Ross epitomized the “mixed-blood” Cherokee: Accustomed to trading with whites, they made up the leadership class. These Cherokee followed European fashions and rejected the old ways of tattooing the skin, shaving the head, wearing nose rings, and stretching one’s ears with hoops.

Like many Cherokee, Ross was barely Indian at all by blood, no more than one-eighth; his father was a trader born in Scotland. What put Ross in a position of leadership was the fact that his mother’s brother was John Ross, the formidable elected chief of the Cherokee Nation, who had a similar mixed background.

With his Scottish heritage, William Potter Ross was educated at Presbyterian schools and Lawrenceville Academy (he was salutatorian) before entering Princeton in 1838, one of many Southerners to attend in those antebellum days. Twelve members of the Ross family were enrolled at Lawrenceville around this time, and three went on to Princeton. William Potter Ross’ brother, Robert D. Ross 1843, attended medical school at Penn and became a pioneering doctor among the Indians.

In the mind of John Ross, William’s Princeton education was preparing him for eventual leadership of the tribe, and he paid the tuition when William’s father could not. After 175 years, there are few clues as to what his undergraduate experience was like or whether he was regarded as an outsider. But the years Ross spent under the elms at Old Nassau were dark ones for the Cherokee. The tribe had been split on the question of whether to emigrate west, as the federal government wished it to do. John Ross opposed moving, but his rivals signed a treaty with the U.S. government that gave the Cherokee new lands in Indian Territory, today’s Oklahoma. John Ross’ followers were sent west on the Trail of Tears, where his wife was among the estimated 4,000 Cherokee to perish.

As a freshman at Princeton, William Potter Ross received reports of the hellish trek, fuming to his uncle that God ought to curse the United States “with some calamity for their cruelty.” Upon graduation, he traveled to Indian Territory to join his beleaguered people, then deeply split by factions and ruthless infighting. Avoiding these disputes, Ross taught school for a year, then became clerk of the tribal senate and, in 1844, editor of the newspaper The Cherokee Advocate. (The Advocate succeeded the Cherokee Phoenix, published in Georgia prior to removal by Elias Boudinot, who had changed his name from Buck Watie to honor a New Jerseyman who advocated Indian rights: Princeton trustee Elias Boudinot.)

The Cherokee respected Ross’ literary and oratorical gifts as honed at Princeton. By 1847 he was representing the Cherokee in front of the U.S. Congress in Washington, the first of a long series of visits there. Far from fomenting revenge against the federal government for its brutal treatment of his tribe, Ross settled near the U.S. Army base at Fort Gibson, Indian Territory, where he ran a profitable store. John Ross lived comfortably nearby. “William Potter Ross had witnessed what we would call ethnic cleansing or even genocide,” says Kevin Gover ’78, director of the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., and a member of the Pawnee tribe of Oklahoma. “But as he got older, he must have realized that bitterness and aggressive rhetoric weren’t going to improve the situation.”

The Rosses bore little resemblance to the fiery Native American activists of the 1970s — they wore no “Indian” garb, attended Protestant churches, and lived to the fullest the life of the Southern planter. John Ross’ pillared mansion lay at the end of a half-mile-long driveway lined with roses, and he owned 100 slaves. In all, the Cherokee had nearly 4,000 slaves, who also endured the Trail of Tears. Whether these slaves’ descendants ought now to be considered citizens of the Cherokee nation has been hotly debated in recent years.

As slave owners, the Ross faction favored joining the Confederacy when the Civil War broke out. William Potter Ross served as secretary at the mass meeting of Cherokee citizens in August 1861 where his uncle urged alliance with Richmond, not Washington. The tribe split once again, with several thousand fighting for each side.

These factions tended to break along old party lines “going back to the removal era,” says Ross Swimmer, a William Potter Ross namesake who was principal chief of the Cherokee in 1975–85 and head of the Bureau of Indian Affairs under President Ronald Reagan. Much bloodshed ensued from these tribal disagreements.

Fighting for the Confederacy, William Potter Ross became lieutenant colonel of the Cherokee Mounted Rifles, all of whose officers were of mixed blood, while the enlisted men were of full blood with striking native names like Moses Bullfrog and Six Killer Hummingbird. The Rifles fought in Arkansas at the Battle of Pea Ridge, some Indian soldiers fearsomely attired in buckskin, moccasins with bells, and turkey-feather headdresses, with their faces painted black. A few engaged in scalping, which the Northern press seized upon as a “carnage of savagery.”

William Potter Ross seems to have played no role at Pea Ridge and no doubt recognized what damage it did to Easterners’ impression of Native Americans. He now foresaw the inevitable Union takeover of Indian Territory. Ross was briefly arrested by the bluecoats, then his store was burned by rival Indians who condemned his collaboration with the occupying Federals. Ross had been providing food and supplies to Cherokee refugees who faced starvation as the region descended into chaos and guerrilla warfare.

John Ross died shortly after the war ended, and his nephew William assumed top leadership of the shattered Cherokee Nation. Through fighting and disease, its population had plunged by one-third since 1860, to under 14,000. “Everything has been changed by the destroying hand of war,” William Potter Ross wrote to his son. “We have not a horse, cow, or hog left.”

Now the Princeton graduate would play the leading role in rebuilding and defending the tribe in the postwar years, as Anglo settlers began flooding westward along the lines of the new railroads. In the face of these outside dangers, “he fought to unite all the Cherokees,” says Catherine Foreman Gray, history and preservation officer for the Cherokee Nation. “That’s what he’s best known for today.”

Ross journeyed to Washington to help negotiate a new treaty with the U.S. government, an effort that Professor Hoxie calls “a remarkable achievement” toward continued autonomy for the Cherokee Nation, given Uncle Sam’s anger about its having joined the Southern rebellion. Yet the Cherokee were forced to make concessions, including two railroad rights-of-way through their lands, which were whittled down in size.

Remembered by a contemporary as “a profound thinker, ready writer, and a fluent speaker,” Ross visited Washington repeatedly during these years, testifying before congressional committees and even meeting with President Ulysses Grant in 1876. Ross ceaselessly advocated for ongoing Indian rule over Indian land, even as more and more white settlers demanded the right to occupy these fertile yet sparsely populated tracts. Economic imperatives helped drive the push for opening Indian Territory to whites, but more important, Hoxie believes, was a racist conviction that Native Americans ought not be granted exclusive control of lands within the United States: “American politicians said, ‘You can’t have a nation within a nation.’”

Ross urged exactly that. In a stirring speech to fellow tribesmen in 1874, he demanded that Washington follow the example of Italy and guarantee the autonomy of Indians the way Rome, in the 1850s, had allowed San Marino to exist as its own, wholly surrounded principality. The Cherokee and Uncle Sam ought to cooperate and trust each other, Ross argued. Only the “protecting arm of the federal government” could ensure that Indian Territory not be overwhelmed by white settlers, he added, which would lead finally to “extermination” of the native peoples.

And yet all of Ross’ efforts, in the end, came to nothing. He watched in dismay as crime surged in Indian Territory, Texas cattlemen swept through, and white sharecroppers gained a toehold. In 1889, two years before Ross’ death, the first non-Indians were allowed to buy acreage, triggering the pell-mell Land Rush. In 1898, Congress finally abolished the powers of the tribal government altogether.

Recent decades have witnessed a resurgence of the Cherokee, who since 1975 have again governed themselves on 7,000 acres, the heart of their resettlement lands in northeastern Oklahoma from 175 years ago. Then-Principal Chief Swimmer led that movement toward self-rule. “That’s what Ross had in mind back then,” he recalls. “It followed the path he was leading us on.”

“I think we are stronger than ever,” historian Gray says with satisfaction, pointing to more than 300,000 Cherokee Nation citizens living worldwide, 120,000 of them on the tribal-jurisdiction lands. That’s an increase of 2,000 percent since Ross viewed the devastation of the Civil War with despair.

Of 566 tribes officially recognized by the U.S. government today, the Cherokee are the largest, with a $1.3 billion economic impact in the state. “They survived all these traumas,” says Gover, “and today they are thriving. That is a remarkable story of human stubbornness and resilience,” in which a Princeton alumnus played an important role.

“The Hon. William Potter Ross died suddenly, July 20, of heart disease at his home in Fort Gibson, Indian Territory,” The Daily Princetonian reported in 1891. Ross had been, the student editor said with pride, “a brilliant orator and the leading statesman of the Cherokee nation.” On his marble tombstone at Fort Gibson appear the carved words: “Educated at Princeton College.”

W. Barksdale Maynard ’88 is the author of six books on American history, including Princeton: America’s Campus and the new The Brandywine: An Intimate Portrait. He is a lecturer in the School of Architecture.