Knowing he had only months — possibly just weeks — to live as he fought the last stages of pulmonary fibrosis, John Hall Fish ’55 wanted to bring together the people who were important to him through Princeton AlumniCorps, a Princeton-based group that promotes civic action.

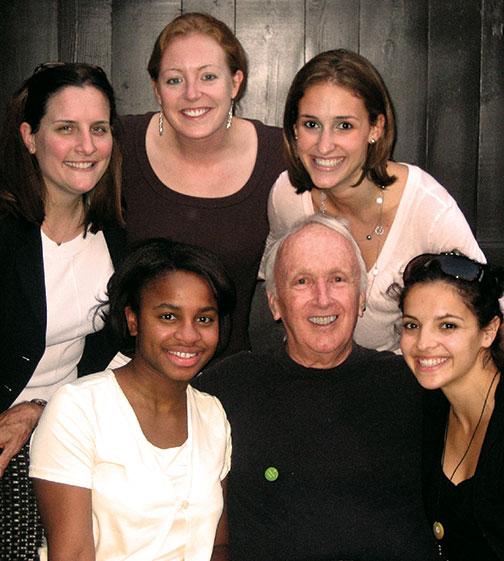

So just four weeks before his death June 10, colleagues and friends celebrated his life at a party in Fish’s adopted hometown of Chicago. More than 80 people came to honor Fish, who used a wheelchair and oxygen, and more than 100 testimonials filled a book of tributes. Many recalled how Fish had opened their eyes to a different world, changing them forever. He had a name for the experience: “creative dislocation” — moving out of one’s comfort zone.

After earning a divinity degree and serving five years as a Presbyterian minister in Michigan, Fish received a doctorate in social ethics from the University of Chicago and taught there for a year. In 1969, he joined the founding faculty of the Urban Studies Program of the Associated Colleges of the Midwest, in which college students spent a semester in community service in the city.

“The city is the teacher,” Fish told the Chicago Tribune in 1995. “Students learn not only about urban reality and issues, but also about themselves and their capacities. They become, we hope, active, caring, street-smart citizens.”

In 1989, when ’55 classmates proposed Princeton Project 55 — the forerunner of Princeton AlumniCorps — to spark civic engagement and promote social justice, Fish became the founding director and, later, national director of Project 55’s Public Interest Program (PIP). From its beginnings in neighborhood nonprofits in Chicago, PIP expanded to other cities and has placed more than 1,500 Princeton students and alumni in yearlong community-service fellowships and summer internships.

“John believed a society that has more justice needs less charity,” says Ralph Nader ’55, who had developed the idea for Project 55. “Justice is prevention of pain and anguish and deprivation, while charity is palliative. John was very grounded in what he wanted to change: He experienced it, he studied it, he felt it ... and then he worked to change it.”

Early PIP board members remember how Fish, in 1990, insisted that they spend a weekend immersed in urban Chicago. They visited schools, hospitals, community-service organizations, and “slept on the floor somewhere,” recalls Kenly Webster ’55, chairman of AlumniCorps’ board. “John wanted us to see firsthand a big city’s problems and a big city’s efforts to treat those problems.”

In Fish’s final sermon, delivered April 27 at University Church on the University of Chicago campus, he said, “What we see depends on where we are located ... not only our geographic location, but our race, gender, social class, our family, our schooling, our upbringing.

“If we do not change our location, then we are simply continuing along a path that is laid out for us, that is prescribed for us. We never grow.”

Fran Hulette is PAW’s Class Notes editor.

Fish explores “creative dislocations” in his final sermon, delivered in April 2014.