When Apple rolled out a new music service earlier this year, it featured a live radio feed hosted by a DJ whose offbeat playlist, The New York Times said, would appeal to anyone who “would enjoy Princeton’s very eclectic WPRB.”

Far beyond Princeton, WPRB — renowned for helping to introduce unfamiliar music that later became mainstream — is famous. This fall the station, heard at 103.3 on the FM dial and at wprb.com online, is marking its 75th anniversary, celebrating its achievements and considering its future in today’s fast-changing digital age.

The story of WPRB is highlighted in an exhibition running through Reunions at Mudd Library, which features record covers from bands utterly obscure, scrawled with critical appraisals in ballpoint pen by student DJs. And the station has launched a history website with audio clips (www.wprbhistory.org) that illustrate an increasingly diverse musical landscape at century’s end, ranging from indie rock to Texas border songs to the so-bad-it-just-might-be-good. “You had these DJs who were really smart and thoughtful and curious about music,” says public-service announcer Peg Laird *02, who met her husband, Phil Taylor ’00, at the station. “Whether it was free jazz or little punk bands, they really wanted to find new kinds of sounds and cared about what they were playing.”

Founded in a Pyne Hall dormitory room as WPRU, an AM station, student-run WPRB is independent — a rarity among college stations: It’s governed by a board comprising alumni and students. The station is commercial, licensed by the FCC well before development of the noncommercial and educational lower end of the dial.

For its listeners from the outskirts of New York City down through Philadelphia, WPRB is the source of new and little-known music they can’t easily find elsewhere. For the 50 Princeton students who work there, the station is that and more: a chance to run an independent, nonprofit business, and a campus activity unlike any other. An eclectic mix of students always has distinguished WPRB: “It attracted all types, from technicians, to people really into music, to those who wanted to make money selling commercials,” says John Catlett ’64, who has headed many stations, including Radio Free Europe. “All those types have to work together to make a radio station.”

Princeton’s radio station has been a great success story, perhaps because it draws from some of the University’s strengths. Our musical enthusiasms run far back, to Triangle and the Glee Club in the late 19th century; the first radio appeared in a dorm room 102 years ago. The campus is crowded with engineers who enjoy the technical challenges of managing a student-run radio station. And our love of athletics guarantees a perennial demand for on-air sports coverage.

Radio was in its pre-television heyday — there were 800 stations nationwide — when Henry Grant Theis ’42 founded WPRU in late 1940. He thought Princeton would be perfect for having its own station: A remarkable 94 percent of the affluent student body owned a radio, and local merchants would advertise eagerly, he figured. In those days, the FCC refused to license college stations because they shut down in the summertime, so Theis sought a non-broadcasting method of operation, finally settling on transmission through the University’s underground electrical lines. Undaunted by setbacks, he and friends coupled an antenna to the transformer in the basement of Pyne Hall, with the hope that “signals may possibly penetrate as far as the Graduate College.”

The WPRU studio occupied Theis’ dorm room in 441 Pyne, with “rippled wall curtains” as soundproofing and a bed very much in the way. The cost of everything: $500.

There were many naysayers, Theis recalled in an interview before his death in 2005. President Harold Dodds *1914 was “quite dubious” and feared advertisements on the station might risk commercializing Princeton’s name; undergrads, too, were skeptical. But the station quickly proved popular and gained national attention when radio-show writer Erik Barnouw ’29 applauded its pluck in the Saturday Evening Post.

Thirty-five students were involved by 1941, including lively DJ “Flunks” Fales ’43. Then as now, the station prided itself on the diversity of its offerings, everything from Beethoven’s Fifth to “Scrub Me Mama With a Boogie Beat” — further alarming the administration. WPRU had an educational side, too, broadcasting a debate called “Can Hitler Invade America?” and even preceptorials. Socialist presidential candidate Norman Thomas 1905 and Eleanor Roosevelt both spoke to the station; during wartime, William Rusher ’44, later publisher of National Review, commented on air about international relations. Theis noted with pride the success of his fledgling station, even as he went on to manage WXLC — part of the Armed Forces Radio Service — from a Navy Quonset hut in Alaska.

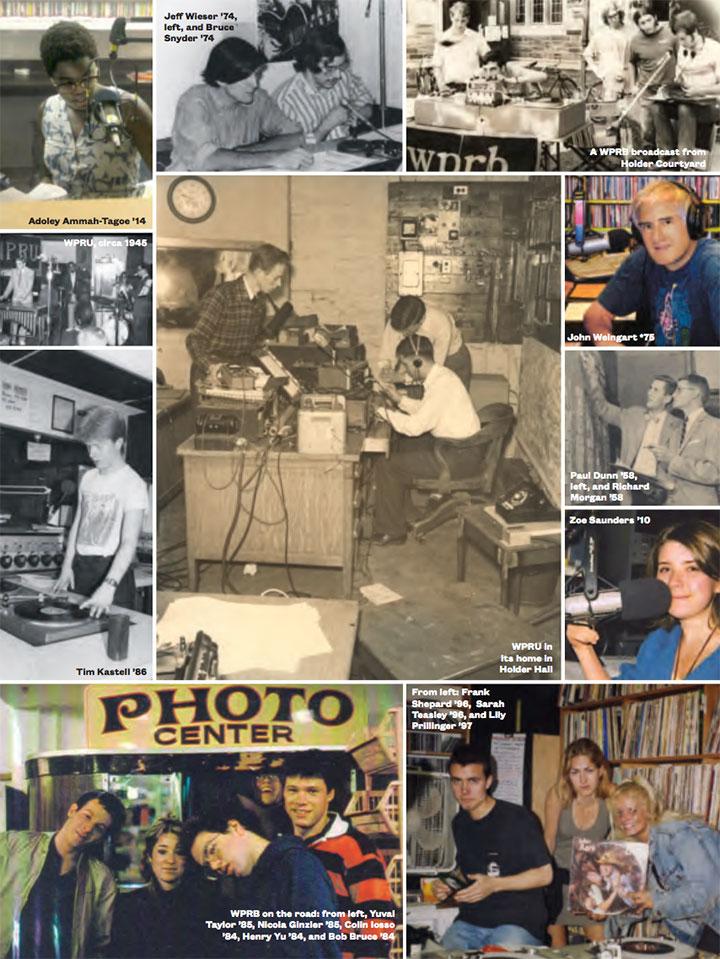

After a year-and-a-half hiatus prompted by a staff shortage during the war, WPRU was revived in March 1945 in the basement of Holder Hall. Its transmitter was war-surplus from a B-17 aircraft; studio equipment later was brought from the atomic test site at Bikini Atoll, where a WPRU alumnus had been stationed. Yale students targeted the station in a daring prank, tying up the DJ during a request show and playing “The Bulldog Song.”

WPRU soon entered its first golden age, with more than 100 staffers by 1954 and a collection of 4,700 records featuring hits by performers like Tony Bennett, Eddie Fisher, and Patti Page. The station expanded to seven underground rooms filled with equipment the students built themselves. In 1955 the FCC changed its rules and offered the station the first commercial license ever given to a college outfit, which renamed itself WPRB and used a new FM transmitter to waft Elvis across much of central New Jersey.

On his show Spins ’n’ Needles, Ward Sylvester ’61 promoted early rock. “I didn’t actually spin my own records,” Sylvester recalls today. “I had to do hand signals to the engineer on the other side of the glass window.” He credits WPRB for exposing him to “life in the entertainment business,” where fame awaited: Just a few years after graduation he was managing the Monkees and teen idol Bobby Sherman, and later Led Zeppelin would cavort aboard his shag-carpeted Boeing 720B jetliner, the Starship, which Sylvester purchased with Sherman.

A signal boost in 1960 to 17,000 watts made WPRB the most powerful student-operated radio station in the world, reaching more than 5 million potential listeners in three states from a new antenna atop Holder Tower — an addition that the University administration worried was an eyesore. Three years later, students designed and built equipment that allowed WPRB to broadcast in stereo. It had entered the big leagues: “The announcers don’t razz their roommates anymore,” a journalist noted. Now WPRB featured Brahms to the Beatles in FM stereo. DJs of the decade claim having been among the first to play songs like “I Want To Hold Your Hand” and “California Dreamin.’”

“We were the leading edge of the Golden Age” of rock, says John Platt ’70, who is now communications director at WFUV, Fordham University. With its massive reach, WPRB was no typical college station, says Robert Orban ’67, famous in the field of audio processing. “It was enormously important to my career, because I saw how professional FM radio was done.”

Orban’s colleague Boyd Britton ’70 went on to become the radio personality Doc on the Roq on KROQ in Los Angeles. “I fell in love with broadcasting at WPRB and have done it ever since,” Britton says, looking back fondly on his far-out college radio show of “alternative-style news with skits, sound effects, and weirdness.”

WPRB always had a news division (today, the station airs its News and Culture program every Monday at 6 p.m.), training students like Charles Gibson ’65, who would go on to anchor the evening news on ABC. Catlett recalls how a “white-faced freshman” burst in to announce on-air that President John F. Kennedy had been shot. When President Lyndon Johnson visited campus, Paul Friedman ’66 undertook a live broadcast: “It was a major event in my life. I did the coverage and said to myself, ‘I want to do this!’” A decade later he was producing the Today show on television. At the height of the Vietnam War protests of 1969, WPRB microphones recorded hours of teach-ins and rallies; seven minutes of tape from that November — “moratorium coverage” — survive, a rare audio portrait of that tumultuous age. Covering a massive anti-war protest in Washington later that fall, WPRB’s student reporters were able to talk to young demonstrators in a way that gave them a distinct advantage over older, professional “establishment reporters.”

Even as WPRB enjoyed a ’60s heyday, the Holder facilities were famously inadequate. “We had professional equipment,” says Catlett, “but it was kept together with rubber bands.” The record collection was a shambles, soundproof tiles grew yellow from cigarette smoke, and a 1969 report complained that the below-grade studios were “laced with University plumbing” that provided “esoteric background noise” that puzzled listeners.

Floors were often wet after a rain, and the studios had no air conditioning. “To this day, the smell of mildew brings back memories,” chief engineer Moe Rubenzahl ’74 remembers. When, in the 1970s, a sodden rug from the main control room was laid in Holder Courtyard to dry in the sun, a little crop of marijuana plants sprouted. “It was not unusual to find shirtless DJs trying to avoid sweating on the LPs,” Rubenzahl says. “Given the dampness, the mildew, and undergraduate hygiene standards, the place was sometimes ripe.”

But in the age of the Beatles and Rolling Stones, record companies turned to college stations as a lucrative pipeline to the new generation. And these young people were avid about the airwaves: 82 percent of Princeton students were tuned in to WPRB at the ’60s’ end, a survey showed.

Wooed by big-city stations and industry professionals alike, a few WPRB DJs found themselves superstars. Jon Taplin ’69 spent his weekends traveling from campus to campus as road manager for singer Judy Collins, getting back in time to host Sunday afternoon’s R&B and rock program Dead Air on WPRB: “We had no format we had to stick to, and we could play whatever we liked.”

The youthful Taplin also managed The Band and swooped into Woodstock by helicopter weeks after graduation, landing right behind the stage. “Flying over the crest of the hill and seeing 300,000 people — it was like Cecil B. DeMille,” he recalls.

DJ Platt, who had grown up pretending he was a radio host, making recordings on his father’s Dictaphone, proved similarly fortunate. As WPRB program director, he regularly fished into the messy bin of new music that everybody called The White Rabbit, after the Jefferson Airplane psychedelic song. “It was funky,” he remembers of the chaotic station, “but it was radio — there was nothing more exciting. We were doing what the professionals were.” By junior year Platt had landed a job as DJ at Philadelphia’s rock station, WMMR: “They put a 20-year-old on the air!”

“It was a very heady experience being involved with WPRB in those days,” says Art Lowenstein ’71, who interviewed James Taylor for the station. “We had more freedom and less constraints than anybody’s ever had in radio, and there was nobody at the University looking over our shoulder.” The sociology department even gave him permission to write his senior thesis as 13 radio broadcasts about “The Woodstock Generation,” and Lowenstein traveled from music festival to music festival, gathering material on reel-to-reel tape.

Throughout the ’70s, WPRB was a way of life for the students who volunteered there. “For better and worse, Holder was a very lived-in place,” remembers John Weingart *75, who showed up in fall 1973 and announced, “I’d like to do a radio show.” At first alarmed by the unheard-of intrusion of a graduate student, the undergrads granted his wish. Weingart’s folk-and-blues show, Music You Can’t Hear on the Radio, remains on the air today.

“We all bonded together in that one tiny, dank place,” says Mimi Chen ’79, laughing as she remembers. A classmate had dragged her to take the required FCC licensing test, but Chen soon discovered the thrill of “sitting there, broadcasting live,” especially during the 1977 New York blackout when certain rival stations were disabled. Quickly she was lured away by WMMR, where the sophomore DJ rode in a limo with singer Tom Petty and met “the people who threw the furniture out of hotel-room windows” in those palmy days of rock ’n’ roll excess. Today Chen is a DJ at KSWD, Los Angeles. “I owe my career to WPRB,” she says. “That’s where I learned how to do radio in a very free-form format.”

“There was such a sense of freedom and experimentation,” recalls Marc Fisher ’80, a Washington Post editor and author of a book about the history of rock radio. “The great advantage was that you could take liberties and try new things. College radio today is much more pre-professional and serious.” Fisher did an improvisational middle-of-the-night program called The Magic of Radio, where anything might happen: snippets of “classical Top 40,” a country set (with only songs about drunks), a whimsical visit from a Trenton stripper. He occasionally was joined on the show by his friend David Remnick ’81, a “radio fanatic” from childhood and today editor of The New Yorker who recalls, “It was a dump full of pizza boxes, and it smelled like the carpet at Dial Lodge, but it had a terrific record collection!”

Things are changing at WPRB. In 2004 the station moved to new studios in the basement of Bloomberg Hall, sending signals to a soaring antenna — 989 feet high — near Quakerbridge Mall along Route 1 to blanket Philadelphia, the nation’s eighth-largest radio market, and even beyond. The tidy, gray-carpeted rooms with neat wood trim bear no resemblance to the old shambles in Holder. But the station faces an altered landscape. “College radio matters much less now,” says former DJ Taplin. “Bands use Internet platforms to get fans engaged.”

College stations still abound — there are a dozen in New Jersey alone — but many are fighting to remain relevant. Radio has shed much of its cultural cachet for the high schooler: “All of us had grown up listening to radio,” says Paul Dunn ’58. “Undergraduates come in today with little knowledge of it.” Yale’s once-renowned WYBC now confines student shows to online: “Nobody at this school owns an FM radio,” admits the office manager.

Those 50 students at WPRB today are down from more than 100 at its peak. (Partly to engage more of the campus, in 2009 WPRB purchased the Nassau Weekly.) And about 40 percent of the shows are hosted by outsiders, owing somewhat to waning student interest but also to achieve the ambitious goal of all-night broadcasting without relying on prerecorded programming, board members say. Though the station’s financial health is ensured by a hefty endowment, advertising — which undergraduates sold industriously for years to cover operating expenses — has declined. Today’s students sell public-radio-like underwriting spots instead, and there are on-air community fundraising drives, as well as fundraising online.

But down in the Bloomberg basement studios, surrounded by glowing consoles, microphones, and taped-up notices affixed to glass walls, WPRB students remain passionate about the cause. “We like playing underground stuff,” says Zena Kesselman ’17. Things like music by Sneaks (described by WPRB’s educational adviser as “a one-woman spoken-word/rant project with primitive bass and drum”) and “Peru Boom: Bass, Bleeps, and Bumps from Peru’s Electronic Underground.” “We are very much against the mainstream,” Kesselman says.

“A lot of us struggle with, ‘What are we here for?’” she says of the current staff. “Can radio become what it was in the ’70s or ’80s?” It has great advantages over the Internet, she believes: “It’s still local and homegrown, and it can bring people together on a community level.”

Many station alumni share her optimism. “I still think there’s a role for radio,” says former WPRB DJ Platt. In an age when soulless computers choose most station playlists, “WPRB can represent a noncorporate, opinionated, thoughtful point of view” and feature songs that are totally unexpected. From down in that Bloomberg Hall basement, the voice of Princeton endures.

W. Barksdale Maynard ’88 is the author of seven books including Princeton: America’s Campus and The Brandywine: An Intimate Portrait.

LISTEN to archival audio from WPRB in Gregg Lange ’70’s Rally ’Round the Cannon column, along with reminiscences from station alumni John Shyer ’78 and Sally Jacob ’88.