A century after throwing out the ceremonial first pitch for Game 2 of the 1915 World Series, Woodrow Wilson, baseball in hand, smiles from the wall of the Wilcox dining hall — cheerful, confident, and twice as big as life.

A member of the Class of 1879, Wilson spent 24 of his 67 years at the University, as striving student, revered professor, and reformist president. He coined the unofficial motto “Princeton in the Nation’s Service” in an 1896 speech and went on to serve as New Jersey governor and U.S. president, capping victory in World War I with the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize. Decades after his death, a grateful Princeton memorialized his achievements in the names of Wilson College and the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs. It’s not only in that floor-to-ceiling photo-mural that he looms larger than life.

“He built Princeton,” says James Axtell, retired professor of history at the College of William and Mary, who has written about Wilson’s educational legacy. “He put it on the path to becoming the university it is today.”

But the tumultuous events of last fall — a vocal advocacy campaign, a 33-hour student sit-in at the Nassau Hall office of President Christopher L. Eisgruber ’83, and the establishment of a Board of Trustees committee charged with re-examining the ways Princeton commemorates Wilson — have highlighted a different aspect of his record, one that, although no secret to historians, is less familiar to the general public. Woodrow Wilson, activist Princeton president and eloquent leader of wartime America, also held repugnant racial views, strove to keep blacks out of the University, and presided over the segregation of the federal workforce.

“Just as our nation re-evaluated its bizarre attachment to the Confederate flag, it is time for our University to re-evaluate its blind veneration to its deeply racist demigod,” Wilglory Tanjong ’18, a member of the activist student group the Black Justice League (BJL), wrote in The Daily Princetonian in late September. Among the demands BJL made during its sit-in was that Princeton rename the Woodrow Wilson School and the Wilson residential college and remove the Wilcox mural.

Princeton’s reassessment of Wilson comes as other campuses reckon with their own racial histories. At Yale, trustees will decide this semester whether to remove the name of John C. Calhoun — member of the Yale class of 1804, South Carolina senator, U.S. vice president, and defender of slavery as “a positive good” — from one of its 12 residential colleges. Georgetown plans to rechristen two campus buildings named for slaveholding university presidents. Both Harvard and Princeton have stopped referring to the heads of their residential colleges as “masters,” calling the title a potentially offensive anachronism. Last spring, South Africa’s University of Cape Town took down a statue of British colonialist Cecil Rhodes, and an Oxford University college is considering doing the same.

The Wilson controversy draws its energy from the confluence of several intellectual and political currents, scholars say. For the past decade or two, American historians have paid increasing attention to the role of race in the years between post-Civil War Reconstruction and the 1960s civil-rights movement. More recently, the Black Lives Matter campaign has brought heightened scrutiny to issues of institutional racism, especially police treatment of African Americans. Undergraduates who grew up with the promise of equality implied by the election of a black president are reaching maturity in an unsettled world of economic crisis, violent conflict, and debased political discourse, and the ubiquity of social media connects them to all of it.

The intersection of these pressures, scholars say, helps explain why, nearly a century after his death, Woodrow Wilson is suddenly in play.

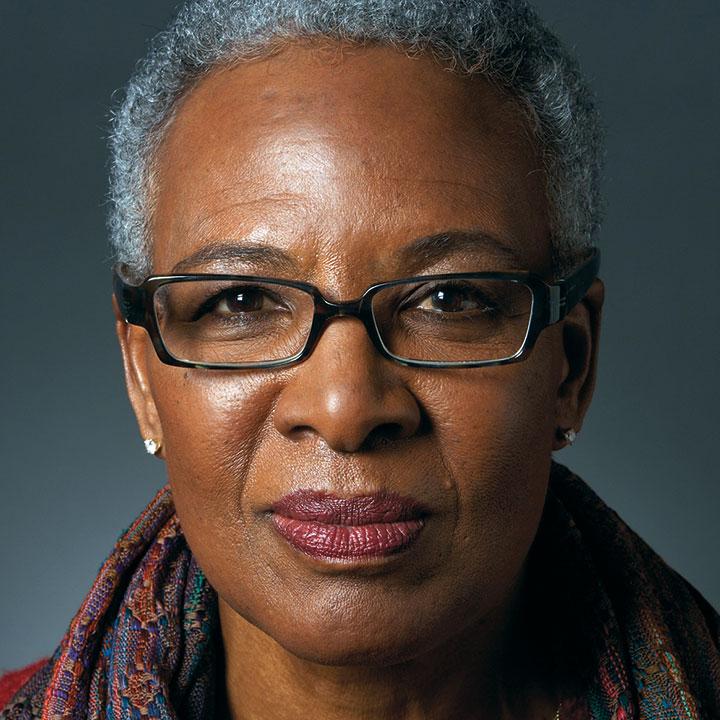

“It’s all about the questions we ask. The questions have changed,” says Nell Irvin Painter, retired professor of American history at Princeton. “I mean, the questions always change. That’s why we keep writing history.”

“[Wilson] essentially resembled the great majority of white Northerners of his time in ignoring racial problems and wishing they would go away.”

Historian John Milton Cooper Jr. ’61, Wilson biographer

Born in Virginia in 1856, the son of a Presbyterian minister, Woodrow Wilson grew up in four Southern states. Although his family’s roots in the region were shallow, and Wilson lived most of his adult life farther north, some scholars trace his retrograde views to a childhood immersed in the racial mythology of the pre- and post-Civil War South.

Whatever their origins, Wilson’s racial attitudes — enshrined in scholarly writings about American history that can make uncomfortable reading today — were well-established by the time he became Princeton’s president in 1902. The University enrolled many Southerners, and although Wilson appointed Princeton’s first Catholic and Jewish faculty members, he showed no interest in challenging entrenched racial prejudice. “While there is nothing in the law of the University to prevent a negro’s entering, the whole temper and tradition of the place are such that no negro has ever applied for admission,” Wilson wrote in a 1904 letter to a University official. Five years later, when a black man from the South did inquire about attending, Wilson replied “that it is altogether inadvisable for a colored man to enter Princeton.” The University would not award a bachelor’s degree to an African American until 1947, decades after every other Ivy League school.

By the time Wilson was elected U.S. president in 1912, becoming the first Southerner in more than 40 years to hold the office, thousands of African Americans were working for the federal government. Four hundred had ascended to white-collar clerk jobs paying middle-class wages, says Eric Yellin *07, associate professor of history and American studies at the University of Richmond. “They’re under a kind of magnifying glass for African Americans across the country,” says Yellin, whose 2013 book, Racism in the Nation’s Service, chronicles the Wilson administration’s racial policies. “The numbers are relatively small, but they’re incredibly prominent.”

“It’s not a sin of omission if he justified it, if he explained it, if he knew about it and then did nothing to stop it.”

History and American studies professor Eric Yellin *07, University of Richmond

The presence of black workers doing responsible jobs in unsegregated federal offices was a perennial irritant for Southern politicians and their constituents. Early in Wilson’s administration, the Southerners he had appointed to head the Treasury Department and the Post Office, the government departments employing the largest numbers of black workers, proposed a formal separation of their black and white employees. Wilson, who typically let subordinates do their work without interference, concurred. Rows of lockers were erected to divide employees by race, racist middle managers were given implicit license to torpedo black subordinates’ careers, and applicants for Civil Service jobs were required to submit photographs. In departments across the government, black workers were demoted or saw their careers stall.

“The government would remain, in different ways, the vehicle for a rising middle class for blacks,” says Jonathan Holloway, a professor of African American studies, history, and American studies at Yale who also serves as the dean of the undergraduate college. “But there’s no doubt that Wilson set back that process by decades.”

African Americans and the liberal press protested the new color line, and in November 1914, black journalist and activist William Monroe Trotter headed a delegation that visited the White House to complain. Wilson defended segregation as a way to reduce friction between the races and clear a space for blacks to demonstrate their abilities. “Segregation is not humiliating, but a benefit, and ought to be so regarded by you,” Wilson insisted. When Trotter asked Wilson if the “New Freedom” he famously had promised in his campaign meant a “new slavery” for blacks, Wilson lost his temper and ordered the delegation to leave.

Three months later, a former Wilson colleague named Thomas Dixon Jr. proposed a White House screening of a groundbreaking new film based on Dixon’s novelThe Clansman. Wilson agreed, and D.W. Griffith’s landmark epic of the Civil War and Reconstruction, eventually known as The Birth of a Nation, became the first movie ever shown at the White House. Although two recent Wilson biographers, John Milton Cooper Jr. ’61 and A. Scott Berg ’71, conclude that words of praise later attributed to Wilson (“It is like writing history with lightning”) almost certainly were fabricated, the White House screening seemed to put a presidential seal of approval on a work of art that denigrated African Americans, endorsed lynching, and helped inspire the 20th-century revival of the Ku Klux Klan.

Last fall, a century after the film’s White House debut, Princeton’s Black Justice League projected The Birth of a Nation onto the exterior of Robertson Hall, which houses the Woodrow Wilson School, as part of its campaign to highlight Wilson’s racial legacy.

“To say he is no worse than any other racist of his time is not getting it right, either. He is worse.”

Princeton history professor Rebecca Rix

Historians generally agree that Wilson’s racial attitudes were typical of his era and of his party, whose stronghold was the South. “He lived comfortably with the power that Southern Democrats had in Congress and in his party, and race relations were just not front and center in what he was going to do,” says Julian E. Zelizer, professor of history and public affairs at Princeton. “Most Democrats at this period were like him.”

Although Wilson did not share the rabid, obsessive racism of Sen. James K. Vardaman of Mississippi, who supported lynching, or Sen. Benjamin “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman of South Carolina, who spearheaded efforts to disenfranchise black voters, he “essentially resembled the great majority of white Northerners of his time in ignoring racial problems and wishing they would go away,” wrote Cooper, a retired professor of history at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, in his 2009 Wilson biography. Even before Wilson became U.S. president, Cooper notes, the growth in federal jobs for blacks was slowing, as Republicans seeking the votes of white Southerners bowed to pressure from white supremacists, and the Republicans who followed Wilson into the White House did not reverse his administration’s segregation policies. “If there’s a sin, it’s a sin of omission,” Cooper says. “He sanctioned and oversaw a process that was ongoing.”

But other historians note that Wilson, unlike other white racists of his era, had the power to turn his racial attitudes into segregationist policies that ruined the lives of thousands of black Americans — even if Wilson couldn’t single-handedly enact such policies. “He’s not the pivot point there. He doesn’t have that much power,” says Rebecca Rix, an assistant professor of history at Princeton. “But to say he’s no worse than any other racist of his time is not getting it right, either. He is worse. He was in the place to do it, and he had the political motivation to do it, and he did it.”

The rationalizations Wilson offered for segregation, which he justified as a way of promoting government efficiency and the long-term welfare of both races, provided a template for the discrimination that followed, says Yellin, of the University of Richmond. “That kind of talk, I argue, is much more powerful in the long run” than the fire-breathing racism of Tillman and Vardaman, Yellin says. “It’s not a sin of omission if he justified it, if he explained it, if he knew about it and then did nothing to stop it.”

But Wilson’s case is more complicated than that of Calhoun, scholars agree, because his problematic racial policies constitute only part of a larger record of achievement that consistently lands him among the top 10 presidents in surveys of historians and political scientists.

“Even as one of the central architects of modern liberalism, he was nevertheless committed to white supremacy.”

Princeton religion professor Eddie S. Glaude Jr. *97, chair, Department of African American Studies

Wilson appointed the first Jewish Supreme Court justice, the anti-monopolist Louis D. Brandeis; spearheaded the creation of the League of Nations, the forerunner of the United Nations; and articulated principles of national self-determination that inspired oppressed peoples across the globe. His administration launched the Federal Reserve system, limiting the power of the banking industry; reduced tariffs that benefited big business at the expense of consumers; opposed child labor; restricted competition-stifling trusts; aided farmers; and established the progressive income tax. “A lot of those programs created the foundation for what followed,” Zelizer says. “You wouldn’t have the Great Society and the New Deal without the tax system, and without the Federal Reserve, and just without the belief that government mattered.”

Long before the current controversy, Wilson’s record of expansionist government and liberal internationalism made him anathema to some conservatives. But even liberal scholars note that Wilson’s progressivism operated within circumscribed limits.

His domestic policies were designed to aid working-class whites but wrote blacks out of the story, while internationally he projected imperial American power in countries such as Haiti and Mexico, inhabited by black- and brown-skinned populations. “There’s obviously a kind of Aryanism that informed his conception of the world,” says Eddie S. Glaude Jr.*97, a religion scholar who chairs Princeton’s Department of African American Studies. “Even as one of the central architects of modern liberalism, he was nevertheless committed to white supremacy. And to whitewash that, to disremember that, is to engage in a kind of willful blindness.”

For Princeton, in particular, Wilson’s legacy is sweeping, and re-evaluating it in light of his racial record is complicated. When he assumed leadership of the University, Princeton was more genteel country club than world-class academic institution. “Gentlemen, whether we like it or not,” Berg’s 2013 biography quotes Wilson’s predecessor as telling the faculty, “we shall have to recognize that Princeton is a rich man’s college and that rich men frequently do not come to college to study.”

Wilson seized the opportunity to innovate and reform. With no tenure rules to stay his hand, he fired underperforming faculty and hired star professors. He instituted the preceptorial system and staffed it with dozens of dynamic young academics. He restructured the curriculum around a system of distribution requirements and major fields. He raised millions of dollars to fund his initiatives. And he tried — unsuccessfully — to dismantle the exclusive eating clubs and replace them with a system of residential quadrangles. Unlike many other university administrators of his era, who saw their mission as character-building, “he believed in the intellect as the heart of a university,” says Axtell, the retired William and Mary professor.

“Woodrow Wilson really has gotten his due. He’s been really appreciated. His footprint could shrink without his disappearance.”

Princeton American history professor emerita Nell Painter

Under Wilson, Princeton began to acquire the reputation for intellectual rigor and depth that it enjoys today. “It’s because of Wilson that people at Princeton are in a position to question and challenge his views and his legacy,” says Cooper. “He set the ball rolling to becoming the kind of university, the kind of intellectual forum, that it is. That’s his monument.”

But Princeton also has more concrete monuments to its former leader, notably the public affairs school, named for Wilson in 1948, 18 years after its founding; and the residential college, established in embryo in 1957 by students who shared Wilson’s vision of a Princeton without exclusive eating clubs. Whether buildings should be renamed is one of the questions to be addressed by the trustee committee, whose 10 members include Wilson biographer Berg. Eisgruber already has recommended that the Wilcox dining hall mural be removed, though he opposes renaming the residential college and the Wilson School.

Through a website, wilsonlegacy.princeton.edu, and through on-campus conversations planned for this spring, the trustee committee is collecting the opinions of scholars, biographers, and members of the University community.

Although the Black Justice League’s demands go beyond the symbolic memorialization of Wilson, encompassing matters of curriculum, faculty training, and student housing, symbols also matter, says BJL member Olamide Akin-Olugbade ’16. “Princeton has admitted black students now but hasn’t fully confronted its founding and the way that it has been run, particularly relating to black students,” she says. Seeing Wilson’s name on a building “contributes to me not feeling completely at home on this campus.”

Chiseling Wilson’s name off a wall or two wouldn’t mean erasing him from the University’s history, notes Painter, the retired Princeton historian. “Woodrow Wilson really has gotten his due. He’s been really appreciated,” she says. “His footprint could shrink without his disappearance.”

But others wonder where to draw the line when assessing historical figures whose real achievements coexist uneasily with their flaws. Should the town of Princeton rethink streets named for slaveholders George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, and John Witherspoon? Should the University reassess other honorees in light of their views, not just on race, but on gender, religion, or sexual orientation?

“We can all agree Woodrow Wilson is a racist,” says Josh Zuckerman ’16, a member of the Princeton Open Campus Coalition, a student group opposed to the BJL’s demands. “On the other hand, when you look back at history, there’s very, very, very few people of significance who are going to live up to modern standards of morality.”

Problematic names can provide salient reminders of work that remains to be done, suggests Martha Sandweiss, a Princeton history professor who teaches a seminar on the University’s historical involvement with slavery. “I don’t think we do ourselves a service if we erase all trace of these people or their actions,” says Sandweiss, who takes no position on the question of whether Wilson’s name should remain on University buildings. “It’s important for us to be mindful of what happened so that we can understand it, so that we can prevent it from happening again.”

Holloway, the Yale dean, who is African American, served as master of Yale’s Calhoun College for nine years and says he found “mordant humor” in the incongruity of heading an institution named for a white supremacist. “It did not cause me pain to walk into the building because I was running the damn thing, and it gave me plenty of opportunity to talk about this,” he says. And, he notes, removing symbols of racial injustice, from the flag of the Confederacy to the name of a building, can never substitute for more concrete progress in remedying institutional racism and discrimination.

“I’m not unhappy the flag came down, but my concern is the flag coming down does not mean that racism ended in South Carolina,” Holloway says. “It did not mean that people now had the equal access to job opportunities that had been denied. It did not change the strength or resilience of the social safety net.” Expunging racists’ names from places of honor may be appropriate, but “if that’s all a university does, then I think universities will have failed in their mission,” he says.

In the fall of 2017, Sandweiss plans to launch a website, based on her students’ work, that will lay out the evidence for Princeton’s long entanglement with slavery. The findings make clear that Wilson is not the only Princetonian with a problematic racial record.

“Our campus has many monuments on it to people who held slaves. People who earned money from slaveholding contributed to our university and taught at our university and were trustees of our university,” Sandweiss says. “But that makes our university just like the United States of America. Liberty and slavery, liberty and racism, have always been intertwined in this university. Princeton is not unique. Princeton is exemplary of the national story.”

Deborah Yaffe is a freelance writer based in Princeton Junction, N.J. Her most recent book is Among the Janeites: A Journey Through the World of Jane Austen Fandom.