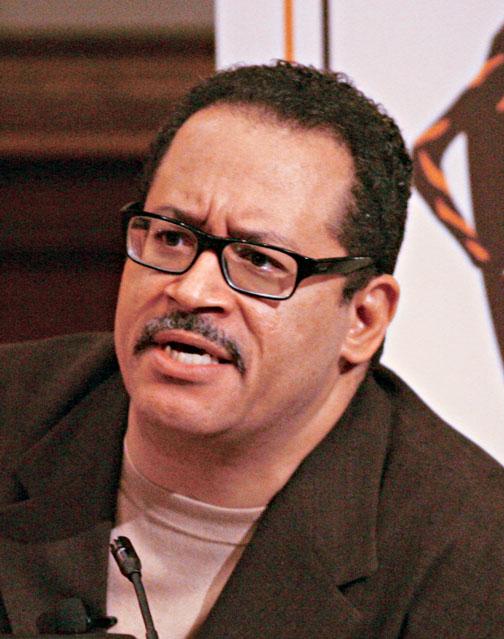

Over the years, Princeton alumni and professors have been leading participants in America’s long national discussion about race. Among the alumni who have helped shape this country’s thinking are public intellectuals such as Princeton professor Cornel West *80 and Michael Eric Dyson *93, a Georgetown University professor who has written more than a dozen books on race and American culture. But today’s conversation includes less-known thinkers like Helen Zia ’73, a child of Chinese immigrants who wrote a groundbreaking book about Asian-Americans, whom she deemed “missing in history” (Asian American Dreams: The Emergence of an American People, 2001); and Kevin Gover ’78, a member of the Pawnee Tribe in Oklahoma and the assistant secretary of the Interior for Indian affairs during the Clinton administration, who now is interpreting and preserving Native American culture as director of the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Indian.

Here are brief sketches of Princetonians who over the last three centuries have influenced the national conversation — for good and for ill.

THE THREE-FIFTHS COMPROMISE

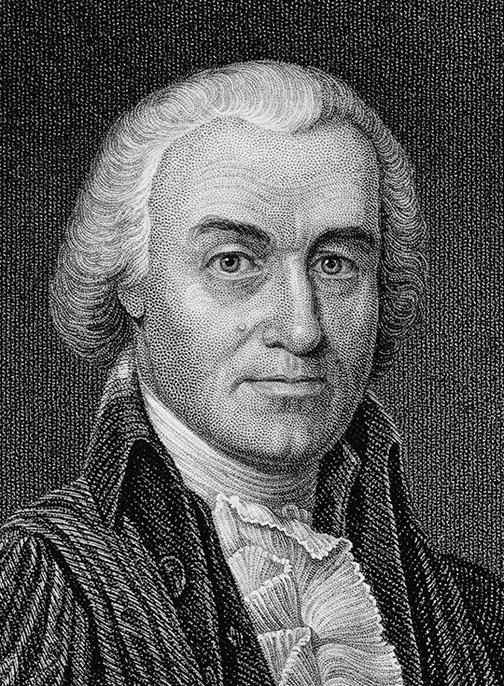

As a Princeton undergraduate, Oliver Ellsworth 1766 founded what became the Cliosophic Society. As a U.S. senator, he drafted the Judiciary Act of 1789, which created the system of federal courts. He served as chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1796 until 1800. But he is listed here because of his role as a delegate to the Constitutional Convention.

After months of debate, efforts to draft a new Constitution had foundered because small states feared that they would be dominated by more populous states. Ellsworth and fellow delegate Roger Sherman devised what came to be known as the Connecticut Plan, which proposed a bicameral legislature in which all states would have an equal vote in the Senate while a House of Representatives would be apportioned based on population.

That begged a critical question: the population of what? Southerners insisted that slaves count in population totals, which would give them more seats in the House and more electoral votes in choosing a president. Northerners objected that this would give the Southerners too much power. To gain support for his Connecticut Plan, Ellsworth became a key supporter of a compromise in which each slave would be counted, for apportionment purposes, as three-fifths of a person. He also spoke out against abolishing the foreign slave trade and in favor of subjecting slavery to state, rather than federal, authority, in both cases to secure Southern support.

The three-fifths compromise exaggerated Southern influence in national affairs until the Civil War. It also probably ensured that when the presidential election of 1800 ended in an electoral tie and the decision was thrown to the House of Representatives, Virginian Thomas Jefferson prevailed, on the 36th ballot, over Ellsworth’s fellow Princetonian, Aaron Burr 1772.

ONE SPECIES OR MANY?

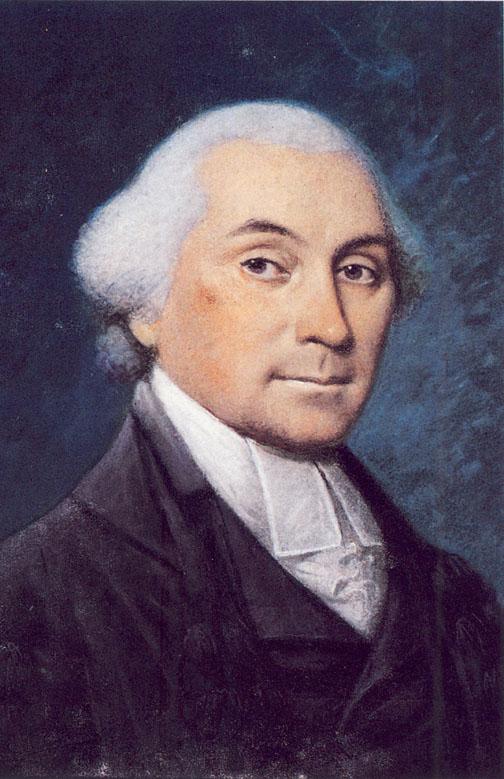

Samuel Stanhope Smith 1769 was the first alumnus to serve as president of Princeton, succeeding his father-in-law, John Witherspoon. Tall, handsome, and commanding, Smith was an acclaimed orator in an age of orators. So great was Smith’s erudition that he was invited to join the American Philosophical Society, in 1785 delivering a revolutionary address, “An Essay on the Causes of the Variety of Complexion and Figure in the Human Species.” In it, Smith asked what accounted for the physical differences among people in different parts of the world. Many natural historians at the time argued that God had created several different species of humans. Drawing more on the Bible than on any scientific investigation, Smith concluded instead that all of mankind belonged to the same species and that any racial differences were due to environment. He cited as an example his impression that slaves who worked in the field had darker skin than those who worked indoors because those who worked indoors had greater exposure to the civilizing influence of their white masters, an observation that was viewed as relatively progressive at the time.

Smith also went out of his way to challenge Thomas Jefferson, who had opined in Notes on the State of Virginia that there were no great African-American writers or artists. Nonsense, Smith retorted, citing the works of Phillis Wheatley, a slave and published poet. How many Southern planters, he asked rhetorically in a clear shot at Jefferson, could have written poems as good? Stanhope Hall is named in Smith’s honor and — in a bit of irony he might have appreciated — became the home of the Center for African American Studies in 2006.

A century later, Arnold Guyot was a professor of geology and physical geography at Princeton and over three decades did landmark work in the study of glaciers, natural formations, and meteorology. Guyot was also an evangelistic Presbyterian, and that put him at the center of what the American Philosophical Society called the “characteristically Princeton effort to reconcile religion and science” during the 1870s and 1880s. Guyot argued that the continents above the equator were geographically more complicated than those below it, and that these characteristics were reflected in the people who lived there. Caucasians, Guyot argued, had perfectly shaped heads, and “all the proportions reveal the perfect harmony which is the essence of beauty. Such is the type of the white race ... the most pure, the most perfect type of humanity.” Guyot’s writings influenced a generation of writers and thinkers and provided ammunition for American imperialism a decade or so later.

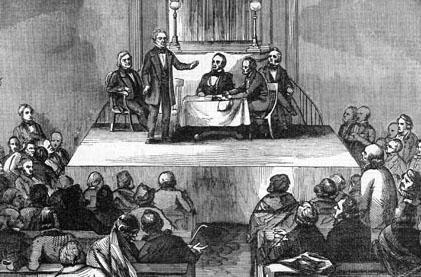

THE AMERICAN COLONIZATION SOCIETY

The American Colonization Society was formed in 1816 with Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and Francis Scott Key as early members, but its driving force was the Rev. Robert Finley 1787, a Presbyterian minister. At the ACS’s first meeting, he proposed that the group found a colony in Africa for free blacks living in the United States. “We should be clear of them,” wrote Finley, who believed that blacks never would be integrated into American society, and would best be able to thrive in Africa. Finley, like others in the society, saw colonization as benefiting both blacks and whites. The effort, he thought, could prompt a gradual, safe end to slavery, and would help spread Christianity in Africa. At the same time, he said that free blacks were “unfavorable to our industry and morals.”

President James Monroe was a strong supporter of recolonization and secured federal funds to found a colony in Africa. The first settlement, near what is now Sierra Leone, was wiped out by disease, and Monroe saw to it that a second group was backed by a U.S. gunship, commanded by Robert Field Stockton 1813. Stockton, who was known as “Fighting Bob,” had a fierce temper and already had fought two duels against British naval officers whom he believed had insulted him. He helped persuade the local African king (some stories say at gunpoint) to sell territory for a new settlement in what is now Liberia, for $300. Ultimately, more than 13,000 people emigrated to Liberia, and the American Colonization Society, which turned its efforts to education and missionary work after the Civil War, remained in existence until 1964.

DRED SCOTT V. SANDFORD

James Moore Wayne 1808 was a rather obscure Savannah lawyer until he was elected to Congress in 1828 as a Jackson Democrat. Andrew Jackson liked Wayne’s strong nationalism and nominated him for the Supreme Court only six years later. Wayne served on the court for three decades, without leaving much of a mark. In 1857, however, he wrote a concurring opinion in the infamous decision in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which held that blacks, whether slave or free, could not be U.S. citizens and thus had no rights under the Constitution. Although Wayne’s concurrence concerned itself only with technical matters of the court’s jurisdiction to hear the case, he stated that “the opinion of the court has my unqualified assent.” One casualty of the Dred Scott decision was the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which had maintained a rough geographic balance between slave states and free. Anti-slavery forces, including the new Republican Party, concluded that under the court’s reasoning there could be no limits on the spread of slavery. Dred Scott, historians agree, made the Civil War all but unavoidable.

SLAVERY OR FREEDOM?

Although many of the Founding Fathers opposed slavery in the abstract, that did not prevent them from holding slaves themselves. In his Lectures on Moral Philosophy, Scottish-born Princeton president John Witherspoon — a signer of the Declaration of Independence — declared, “It is certainly unlawful to make inroads upon others ... and take away their liberty, by no better means than superior power.” In 1789 he headed a committee of the New Jersey legislature assigned to end slavery within the state. Nevertheless, an inventory of Witherspoon’s possessions at the time of his death included two slaves, valued at $100 each.

New Jersey was the last Northern state to abolish slavery, and one of the men responsible for its eventual end was Joseph Bloomfield, a Princeton trustee from 1793 to 1801 and again from 1819 to 1823. Bloomfield served as president of the New Jersey Society for the Abolition of Slavery, and as New Jersey governor in 1804 signed into law legislation providing for the gradual abolition of slavery in the state. As was true in other states, however, emphasis should be placed on the word “gradual.” The statute provided only that the female children of slaves born after July 4, 1804, be freed when they turned 21, and that males be freed when they turned 25. (New Jersey did not abolish slavery until 1846; even after that, the state permitted “apprentices for life.”)

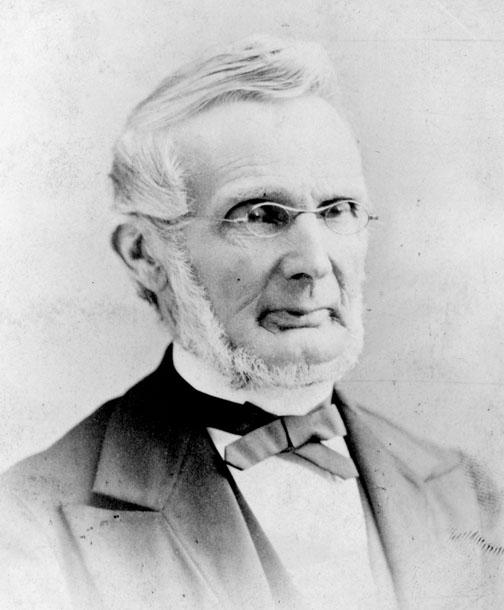

James G. Birney 1810, a Kentucky native who studied under Samuel Stanhope Smith, received slaves as a wedding gift in 1818, but as a member of the Kentucky and Alabama legislatures he began to express growing opposition to slavery. Birney became an early supporter of the American Colonization Society, but by 1834 had grown disgusted with half measures and emerged as an outright abolitionist. Unable to start an abolitionist newspaper in the South, he moved to Cincinnati and began publishing The Philanthropist, which called for the immediate end to slavery and equal rights for African-Americans and whites. Twice, mobs destroyed his printing press.

In 1840 and 1844, Birney was the Liberty Party candidate for president, running on an anti-slavery platform. Some scholars say that his 1844 showing — 2.3 percent of the vote — was enough to tip the close race to Democrat James Polk over the more liberal Whig Henry Clay. In 2008, presidential candidate Ralph Nader ’55 used Birney’s case to argue for the importance of third-party candidates: Birney made slavery an issue that could not be ignored, and without his candidacy, abolition might have taken longer.

EUGENICS

Harry Hamilton Laughlin *17 already had established himself as the managing director of the Eugenics Record Office when he earned a master’s degree in cytology (the study of cells) from Princeton. As a leading voice in the eugenics movement, Laughlin testified in support of the Johnson-Reed Immigration Act of 1924, which cut off immigration from Asia and severely restricted immigration from areas like Southern and Eastern Europe. He also drafted a model law for the compulsory sterilization of alcoholics, epileptics, the mentally ill, the blind, the deaf, and others deemed “socially inadequate.” It was adopted by 18 states. The constitutionality of Virginia’s compulsory sterilization statute, which was based on Laughlin’s work, was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in Buck v. Bell, a decision noted for Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’s dictum that “Three generations of imbeciles are enough.” Laughlin also supported Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act outlawing interracial marriage and was a founder of the Pioneer Fund, which sought to promote “the betterment of the race” through eugenics. In a twist of fate, Laughlin himself was diagnosed late in life with epilepsy.

TWENTIETH-CENTURY SEGREGATION

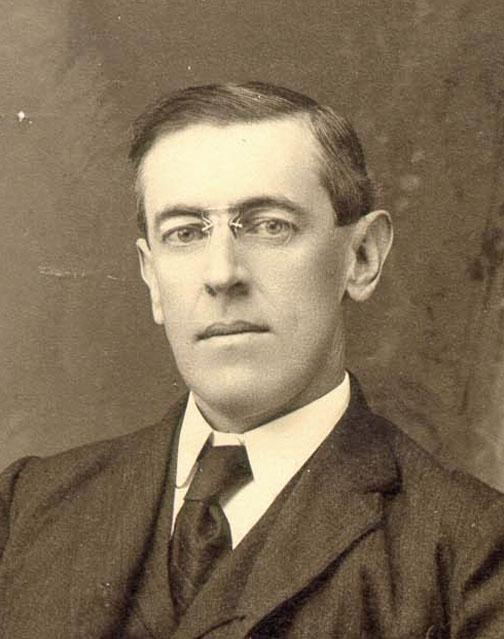

Woodrow Wilson 1879 was only the second Democrat, and the first Southerner, to be elected president after the Civil War, and his record on matters of race reflects that Southern upbringing. Although some historians point to acts that seem to suggest racial open-mindedness, Wilson’s record shows at best insensitivity and at worst outright hostility toward African-Americans. As Princeton’s president, Wilson discouraged black students from applying. As president of the United States, he appointed several Southerners to his Cabinet, who pushed to segregate both the military and the federal civil service. Wilson did not oppose the segregation, and in fact defended it, saying, “The purpose of these measures was to reduce the friction [between white and black workers]. It is as far as possible from being a movement against the Negroes. I sincerely believe it to be in their interest.”

In 1918, Wilson spoke out forcefully against lynching, but historian John Milton Cooper ’61 suggests that the president was motivated more by outrage at the lawlessness of white lynchers than by sympathy for their black victims. Cooper’s observation echoes that of W.E.B. DuBois, who believed that Wilson “was by birth ... unfitted for largesse of view or depth of feeling about racial injustice.”

THE CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT

An iconic moment of the civil rights struggle came on June 11, 1963, when Gov. George Wallace stood in a doorway at the University of Alabama to bar symbolically the admission of two black students. The man Wallace confronted in that doorway, armed with a federal court order, was the deputy attorney general of the United States, Nicholas Katzenbach ’45.

Katzenbach had spent two years in Italian and German prisoner-of-war camps during World War II before graduating cum laude from Princeton and going on to Yale Law School and Oxford as a Rhodes scholar. He joined the Kennedy Justice Department at the suggestion of his law school classmate, Byron “Whizzer” White.

When White was elevated to the Supreme Court in 1962, Katzenbach replaced him as deputy attorney general and worked with attorney general Robert Kennedy overseeing efforts to integrate the University of Mississippi. In 1964, Katzenbach served as President Lyndon Johnson’s liaison with Congress in securing passage of the landmark Civil Rights Act; the following year, Johnson named him to succeed Kennedy as attorney general. During 18 months on the job, Katzenbach helped to secure passage of two other important pieces of legislation, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the Civil Rights Act of 1966.

A tall, slim figure of quiet rectitude, John Doar ’44 is an unsung hero of the civil rights movement. Where Katzenbach had operated largely inside the White House, the Justice Department, and the halls of Congress, Doar worked with local movement leaders in the most troubled parts of the South. In 1960, he became the first Justice Department lawyer to inspect voting conditions in the South. As second in command of the civil rights division during the Kennedy administration, one of Doar’s responsibilities was to escort James Meredith when he attempted to register at the University of Mississippi in 1962. Doar shared a dorm room with Meredith during the first several weeks of the semester and accompanied him daily to class.

Doar worked with Medgar Evers, and on the night of Evers’ assassination in 1963, a crowd of black residents marched to the Jackson, Miss., police headquarters to demand justice. When police attempted to disperse them, it appeared that a riot might erupt, but Doar cooled tempers by wading into the crowd and saying, “You’re not going to win anything with bottles and bricks. My name is John Doar. I’m from the Justice Department, and anybody around here knows I stand for what is right.”

The following year, Doar convinced a federal grand jury to indict 19 men in the slaying of three civil rights workers in Philadelphia, Miss. When a segregationist judge dismissed the indictments, Doar took the appeal to the Supreme Court, which unanimously reinstated them. Eventually, Doar won convictions against nine of the defendants, the first whites ever convicted in Mississippi for violence against an African-American.

“Throughout his legal career,” wrote John Vile in his book, Great American Lawyers, “Doar perfected the art of persuading judges and jurors in hostile environments, and in the process, he persuaded our nation, as well.”

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer.