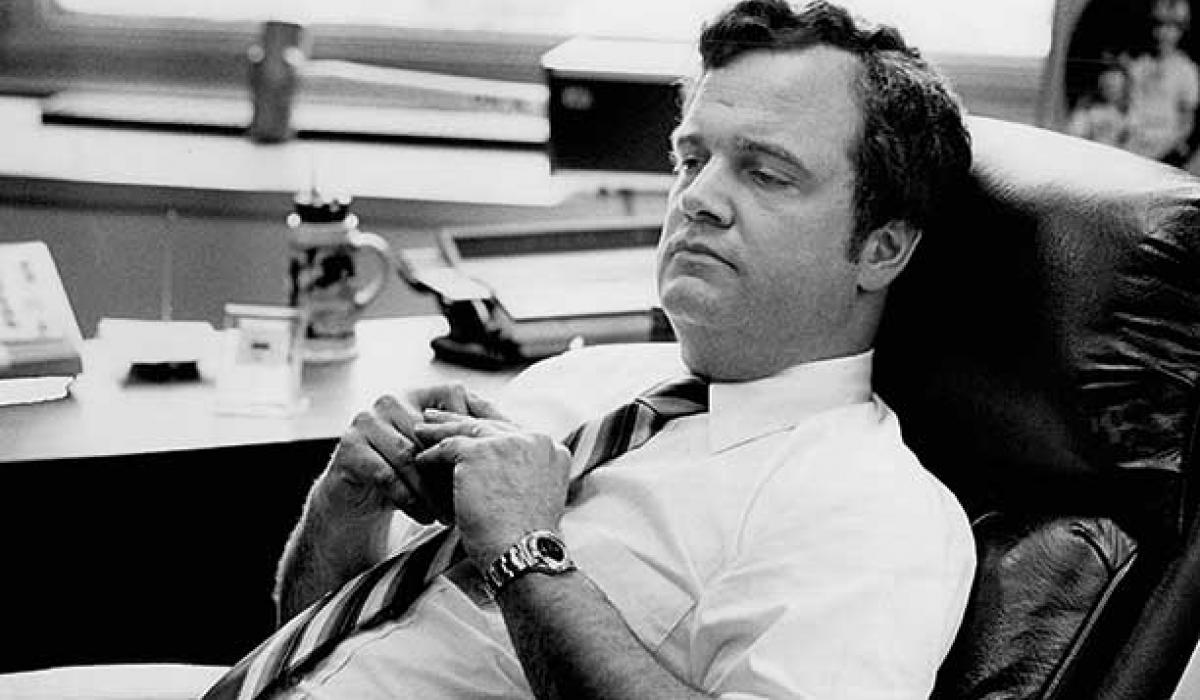

April 26, 1941 • June 3, 2018

AT HOME IN September 1977, Seattle City Councilman Randy Revelle ’63 became agitated about a pack of wolves circling outdoors. He locked his wife and two daughters, 5 and 2, in the house and ran to tell the neighbors.

There were no wolves.

For three weeks, the 36-year-old lawyer acted oddly and dangerously — as when he wielded a fireplace poker like a sword in front of his young girls, Lisa and Robin. His wife called his father, who called the police, but at first the hospital refused to admit him, because Revelle’s plan did not cover inpatient mental-health services.

Eventually Revelle was diagnosed with bipolar disorder and prescribed lithium. It worked.

Four years later, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, with Revelle’s cooperation, reported on his condition, and the Princeton alumnus found a new purpose: sharing his story to transform the way we think of mental illness and the way we deliver health care. As one of the nation’s first politicians to face the stigma of mental illness head-on — a few years after Thomas Eagleton had been dropped as the Democratic vice-presidential nominee when it was revealed he’d received electroconvulsive treatments for depression — Revelle was called by The Seattle Times “a hero in the field of mental health.”

A third-generation Seattleite whose family included one of the founders of the Pike Place Market, Revelle majored in the Woodrow Wilson School and was an ROTC battalion commander. “He was highly organized, and would organize us,” says Hilton Smith ’63, a member of “The 231 Club,” seven roommates from 1938 Hall who gave Revelle the nickname “Mother Randy.”

After a year of study in France, law school at Harvard, and a stint in the military, when he worked as an editor for Defense Secretary Robert McNamara, Revelle and his wife, Ann Werelius, returned to Seattle. There, Democratic Sen. Henry M. “Scoop” Jackson, who had hired Revelle as a summer intern several years before, suggested that the young man get into politics. He did, working on political campaigns and winning a spot himself on the City Council in 1973. It was during his successful campaign eight years later for King County executive, chief administrator for the state’s second-largest government, that local media first reported on Revelle’s bipolar disorder.

In his years in government, he focused on issues ranging from public safety to health to conserving farmlands, forests, and shorelines. But it was in his more than two decades of work at the Washington State Health Care Commission and as a lobbyist that Revelle pursued the cause for which he had a true passion: treating mental illness the same as physical illness. In 2005, a state mental-health-parity bill he had pushed was signed into law, requiring large group-health plans to provide equal insurance coverage for mental health. It was later expanded.

“Hundreds of people ... coping with symptoms of depression, anxiety, or any range of mental issues have looked to the father of two daughters and political leader as proof they, too, can live full and productive lives,” wrote The Seattle Times in his obituary.

“To be that forthright, especially in his profession — he had tremendous courage,” says Smith, reflecting on his friend.

Revelle’s stance was grounded in “integrity and telling the truth,” says his daughter Lisa ’95. “There couldn’t have been a better moral compass.”

Constance Hale ’79 is a San Francisco-based writer and the author of six books, including Sin and Syntax.

Listen: Randall Revelle Talks About his First Psychotic Break (New York Times link)