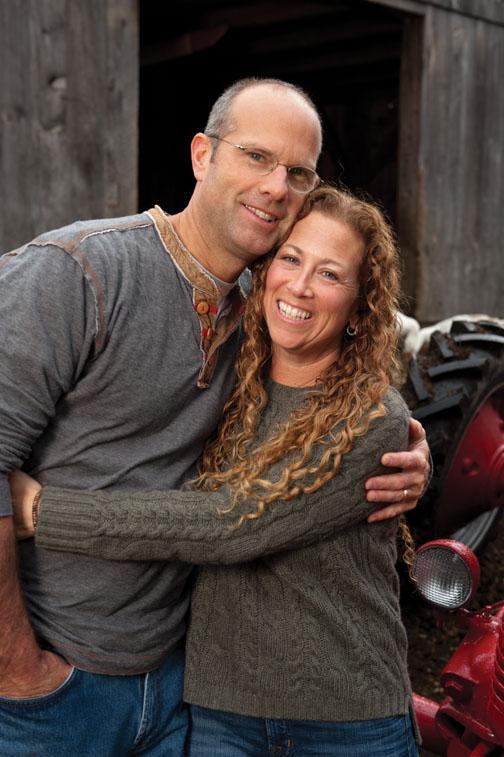

It is a beautiful morning at the New Hampshire home of best-selling author Jodi Picoult ’87, and all seems right with the world. Pumpkin-spice coffee is poured into orange Princeton mugs. Homemade chocolate-banana bread is served with apples picked from one of the trees on the 11-acre farm; chicken soup is simmering on the stove. A pastoral scene beckons outside the window: the working barn built by Picoult’s husband, Tim van Leer ’86, which houses two donkeys, a calf, and chickens, and two geese and dogs roaming nearby.

The peaceful setting is interrupted only by the occasional need to tend to a teenage daughter, Sammy, who has a cold (two sons are students at Yale), and a needy puppy.

Yet the ideal setting stands in sharp contrast to the scenes that Picoult (pronounced “Pi-cóh”) creates in the books she churns out every nine months or so, with about 19 million copies in print. After she leaves the kitchen, she will climb a steep set of stairs to her third-floor study, where she toils in a world of her own making — a world in which characters in her books face violence and abuse, families are in crisis, and children are sick or in trouble.

What if your child considered suicide? Or became deathly ill, or was kidnapped? What if your child was hurt or killed in a school shooting? Or caused a school shooting? These are the kinds of things that keep her up at night — surely, other parents must worry, too. By writing about them, Picoult tries to convince herself that she is immune. “All of those are things I’m terrified of,” Picoult says. “And these are the things that bleed into my writing.” Such is the focus of many of her novels that The New York Times Magazine has called her work “the literature of children in peril.”

One might think, judging from the topics that Picoult covers in her books, that the author is consumed by dread. Not so — not by a long shot. Picoult has a literary light side, too. With her daughter, she co-wrote Between the Lines, a novel for tweens that is scheduled to be published next summer; it’s about a girl who falls in love with a fairy-tale prince who wants to break out of his fictional existence. Each year, Picoult writes an original musical that is produced by a local teen theater group she co-founded, with the proceeds going to charity. For the last four years, she has co-written the musicals with her son Jake. “It gave me a way to share my writing with my kids ... albeit a very different kind of writing,” she says. “Our plays are upbeat and funny and lighthearted — not quite what I choose to do with my novels.”

Still, in her novels — 18 so far — Picoult wraps powerful tales around contemporary controversies from child sex abuse and school bullying to designer babies and gay rights, all with sympathetic characters caught in some moral dilemma. In September, she was writing a novel about a young woman who suspects that an elderly man — a pillar in the community — is a former Nazi; at the same time, she was fine-tuning the galleys of her book Lone Wolf, which will be published in March. In that novel, the children of a man left in a vegetative state after a car accident disagree about whether to take him off a life-sustaining ventilator, and end up in court. The novel explores end-of-life decision-making and the questions raised by advanced medical technologies, including the appropriateness of hastening the end of one life to donate organs that could save others. Picoult “is very good about pushing her audience to grapple with issues that they might not otherwise consider part of the realm of their everyday lives,” says Jill Dolan, a Princeton professor of English and theater and director of the Program in Gender and Sexuality Studies.

Her goal, Picoult says, is to explore what makes people act the way they do, examining issues of morality, justice, and ethics along the way. In many of her novels, she inhabits the various viewpoints of her characters by deftly shifting voices from one chapter to another. Changing narrators offers the author a way to explore different angles of an issue. “I am not going to ask you to read one of my books and change your mind, but I am going to ask you to ask yourself why you believe what you do,” she says.

The relationships and topics Picoult mines for her novels occasionally track the stages of her own life. Her first novel, Songs of the Humpback Whale, published five years after she graduated from Princeton, explores the relationship of a mother and daughter. Picoult’s second novel, Harvesting the Heart, examines how a child changes the relationship between a husband and wife, focusing on a new mother overwhelmed by motherhood; she wrote it when she was a new mother herself, learning to balance her budding career as a novelist while caring for her baby. Writing the book, she says, was “therapy.”

Eventually she began exploring “my worst fears as a mom.” The Pact examines an apparent suicide pact among teenagers; the author has received hundreds of letters from young people who said reading the book turned them away from harming themselves. In House Rules, a single mother is raising a son with autism who is wrongly accused of murder; in Nineteen Minutes, the parents of a high school student who goes on a shooting spree examine their past to see if they are at fault; in My Sister’s Keeper, the parents of a daughter with leukemia decide to conceive a child to be a bone-marrow donor, and the child rebels. Picoult began writing her 2011 novel Sing You Home to ask questions about gay rights; as she was beginning to formulate the story, her oldest child came out as a gay man. “What really began as a theoretical journey as a writer became a very personal one,” she says.

Picoult works in a cozy space with a single window that overlooks her back porch and the woods beyond. She is devoted to her routine. Five-thirty a.m.: Walk with a friend. Eight a.m.: Start writing at the computer, typing so much and so hard as to wear out several keyboards over the years. Write until 4 in the afternoon. That’s the schedule, five days a week.

Above Picoult’s computer, a shelf holds silver block letters that spell out “write,” along with a small Wonder Woman action figure and a Wonder Woman lunch box. Back in 2007, Picoult accepted an offer to write five stories for the DC Comics Wonder Woman strip. She recalled in Playboy about how she wrote herself into the story, telling the illustrator to draw her as an Amazon warrior. “And sure enough, when the issue hit the stands, there was my alter ego,” she wrote, “systematically beating the crap out of Batman.”

A plastic storage container holds her neatly organized research for Lone Wolf. Picoult is a tireless interviewer. The father in Lone Wolf studies wolves to understand their pack qualities; Picoult found an English researcher doing similar work, tracked him down, and spent three days with him and his wolves. For Plain Truth, about an Amish teenager who gives birth to a baby who then is found dead, she lived with an Amish family for a week, helping to milk the cows and make the meals and going to Bible study. For Change of Heart, about a death-row inmate accused of murder, she interviewed an inmate awaiting execution and the prison warden. Picoult recalls how she unwittingly spread out her notebooks on what she later realized was the execution gurney. Those visits to the prison, she says, “deeply affected” her. She continues a pen-pal relationship with one inmate, and says the correspondence has led her to “continue to explore the question of whether someone can atone for a previous sin — or if some sins are unforgivable. I find it hard to believe that people are all good or all evil.”

Although her novels often depict families and children who are struggling, Picoult certainly isn’t drawing from any dark place in her own childhood. The older of two siblings — her brother Jonathan ’91 followed her to Princeton — Picoult grew up in a “disgustingly happy” environment in Nesconset, N.Y., in a development prophetically called Story Book Homes. Early on, writing allowed her to process her feelings about friendships, dating, and then leaving home.

She chose Princeton because of its creative writing program, where author Mary Morris, who now teaches at Sarah Lawrence, became a mentor and taught her how to be her own best editor. Picoult recalls a difficult early workshop when her story was critiqued, but Morris remembers that she saw in her student tremendous promise, along with signs of the work ethic that makes her one of the most prolific writers of her generation. “From the beginning I knew that she was a writer of talent,” says Morris, who advised Picoult on her senior thesis novel. “She was a good storyteller — that was clear to me from the beginning.”

While some critics have called her a “women’s writer,” Picoult finds that label limiting. “Forty-nine percent of my fan mail comes from men,” she says, pointing out that she sees her new book, Lone Wolf, as one that will appeal to men. “You can call me a women’s writer, but also call me a men’s writer, a moral-fiction writer — give me 20 labels.”

She generally is viewed as a writer of commercial fiction, not literature, a distinction that troubles her. Although the line between “literary” and “commercial” fiction can be fuzzy, a literary novel is considered more of a “serious” and intellectually challenging work, while commercial fiction is associated with pleasurable, relaxing reading. When Picoult switched to a more commercial publisher after marketing her first two novels as literary fiction, she brought a fresh approach to the commercial corner of the bookshelf: “There was not much going on in the commercial-fiction world at the time that was taking some kind of ethical issue and dissecting it through a fictional story,” she says.

Picoult is frustrated with the distinction between literary fiction and commercial fiction, which she says is virtually ignored by academia, literary publications, and highbrow literary award competitions. In fact, she says, “the line between [the two] is much more malleable than most people think. ... I’d like to see good writing acknowledged as good writing, period, without making the incorrect assumption that no commercial fiction can be well-written, or that all literary fiction is.”

Picoult made headlines in 2010 when she suggested that reviewers favored male writers. Prompting her was the fact that in August 2010, The New York Times reviewed Jonathan Franzen’s novelFreedom twice in one week. “Look, another white male being reviewed twice in a week by the NYT. Big surprise,” she tweeted. The comment started a discussion in literary blogs and magazines, especially after best-selling author Jennifer Weiner ’91, another writer of commercial fiction, piped in to agree.

Their belief that female writers don’t receive the attention heaped on men soon was backed up by a study by Vida, an organization for women in the literary arts, which found that male authors were more likely than female authors to be reviewed in leading literary publications, including Harper’s, The New York Review of Books, and The New York Times Book Review, and there were more male reviewers than female reviewers. “The thing that upsets me the most about this Franzen controversy,” says Picoult, “is that when a female writer writes with honesty and integrity about the modern American family and the struggles of that family in society, it is ‘women’s lit’ or ‘chick lit’ — and when a man does it, it’s prize-worthy. I think that’s a horrible double standard.” (In an essay published in The Guardian16 months before the controversy erupted, Princeton professor emerita Elaine Showalter noted that when 200 authors and literary experts were asked by the Times to name the best work of American fiction in the last quarter-century, books by only two women — Toni Morrison and Marilynne Robinson — received more than two votes.)

Say what you will about the merits of literary and commercial fiction, Picoult would seem to have the numbers on her side: More than 400,000 people have “liked” her Facebook page, and she receives some 200 emails each day from fans — all of which she answers personally. Her last five hardcover books have debuted at No. 1 on The New York Times bestsellers list.

Last year, Picoult attended Reunions with her husband, marking his 25th. Dozens of alumni and graduating seniors recognized her and stopped to have their photographs taken with her. She says that the attention shocked her; she did not expect so many alumni and students to be among her greatest fans. “That tells me that people with brains are reading commercial fiction, and that there is a subset of commercial fiction that is well written enough to support that kind of intellect,” she says.

Still, Picoult points out that many of the authors of today’s classics — writers like Jane Austen and Charles Dickens — were the popular writers of their day. “I won’t go as far as to say that in a hundred years from now, people will still talk about My Sister’s Keeper,” she says. “But I tell you they are going to talk about Harry Potter.”

Katherine Federici Greenwood is a PAW associate editor.