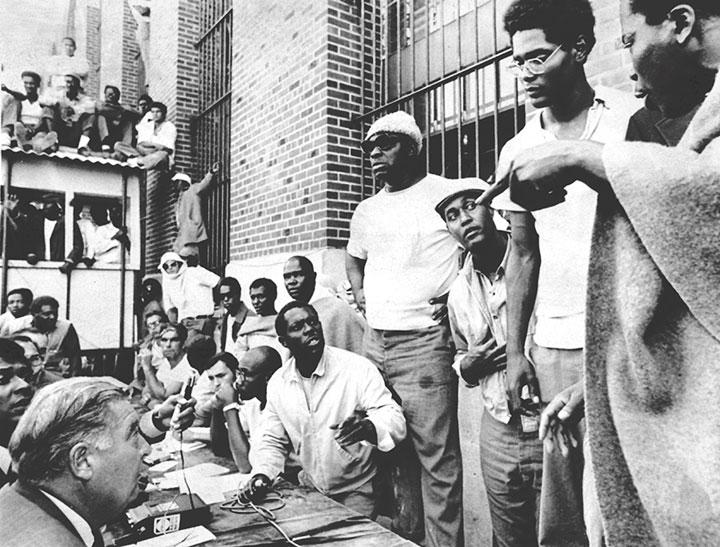

On Sept. 9, 1971, an impassioned speech by a bespectacled 21-year-old prisoner at Attica Correctional facility made national news. “We are men! We are not beasts,” proclaimed “L.D.” Barkley, one of approximately 2,400 men at the upstate New York maximum-security prison. Inmates had been writing letters seeking improvements in their living conditions for years. Basic medical care was almost nonexistent, and each inmate received only 63 cents’ worth of food and the equivalent of one toilet-paper square daily. An unplanned, violent uprising quickly evolved into an organized rebellion involving nearly 1,300 men in one of the prison yards. They elected speakers from each cellblock and requested outside observers to ensure the state of New York bargained in good faith. They also protected their hostages as bargaining chips.

Over four days of negotiations, the prisoners got closer to major improvements and a peaceful resolution. But behind the scenes, the state, including the Nelson Rockefeller administration, saw this as an opportunity to show that it was tough on crime. Heather Ann Thompson *95’s Blood in the Water: The Attica Prison Uprising of 1971 and its Legacy (Pantheon), is the first comprehensive history of the rebellion. The book was a National Book Award finalist and will be adapted for film.

The child of activists, Thompson, now a history professor at the University of Michigan, grew up in Detroit during a time of great civil unrest and became interested in writing about social justice issues. Thompson spoke to PAW about her research into the Attica uprising — a project that took 13 years to complete.

What happened at Attica after police stormed the prison in order to retake it?

I was able to show from records — that the state had hoped I would not see — that it had no intention of settling peacefully. Though the state was told that if they went in with force hostages would die, they still sent in several hundred heavily armed troopers and corrections officers. What resulted was a massacre. Thirty-nine men, both prisoners and hostages, were shot to death, including Barkley, and a total of 128 men were severely wounded. And yet — even after the coroner made clear that every death during the retaking had come from guns, and that none of the prisoners had guns — the state of New York chose to indict 62 prisoners rather than to prosecute a single member of law enforcement.

I also make clear, though, that the hostages and prisoners who had suffered so much death and abuse at Attica never stopped fighting to get some modicum of justice. Today we again have a prison crisis of overcrowding and terrible conditions, and I think the book invites readers to rethink this moment in light of all that we now know happened at Attica.

What was your research process?

The state of New York has thousands of boxes of Attica-related documents, but my access to them proved almost impossible. For the last 45 years, police officials and state bureaucrats have actively blocked all attempts to make the Attica records public. I managed to get some records by filing Freedom of Information Act requests, but they were often heavily redacted. Ultimately I had to dig to find this history in other ways. The survivors and the lawyers’ records were invaluable to me, and I also got critical Attica files via state agencies that had copies of, or documents related to, records that the attorney general’s office was making impossible to see. The most important research breakthrough came, however, after I began contacting every courthouse in upstate New York and finally located a huge cache of Attica files. Although these papers were in complete disarray, they were ground zero for me. They allowed me to see exactly what the state of New York knew, when it knew it, and how it was that law enforcement had never been prosecuted.

Notably, all of those records have since disappeared.

Another lucky break came in 2011 when the state police suddenly gave the New York State Museum thousands of artifacts that troopers had removed from Attica during and after the re-taking. They had been holding these items in a 30-foot Quonset hut in upstate New York and had decided to clean house. I was invited by a hapless archivist to help him understand what these items were, and I was stunned. I found myself holding, for example, the stiff, blood-stained clothes of the prisoners and the hostages and the ripped-up photographs of the prisoners’ children. Those artifacts told me so much about how brutal this retaking of Attica had been. These also have been removed from public view.

How do you balance your personal views with the role of impartial historian?

I think if you’re a good historian, it means you look at the documentary evidence no matter where it takes you. Many historians maintain that we must avoid “presentism” or thinking about what the past tells us about today, because that’s sort of writing history backward. I could not disagree more. I think that if we research something within an inch of its life, and it has a bearing on contemporary issues, then we have an obligation to disseminate that research and make it relevant to contemporary policy debates.

I, for example, find myself deeply immersed in the questions facing our criminal justice system today and, whenever possible, I seek to inform the discussions politicians and policymakers are having regarding our prisons and our justice system more broadly, with some historical context. I can see, as a historian, that mass incarceration is one of the greatest civil-rights crises of the 21st century and, as such, we need to know how we got here so that we can remedy it.

Interview conducted and condensed by Elizabeth Vogdes