The Princeton University Art Museum has organized the first major international exhibition of the Berlin Painter, whose elegant red figures on polished black Athenian pottery have made him a celebrity for lovers of classical art.

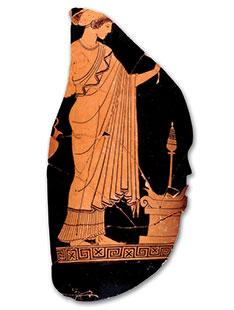

“The Berlin Painter and His World: Athenian Vase-Painting in the Early Fifth Century B.C.,” on view through June 11, showcases 84 vessels and statuettes. These include 54 of the artist’s finest vases, and cover a range of subjects from Greek gods to musical performances to what J. Michael Padgett, curator of ancient art, says “must be the most adorable dog in all of Greek art.” The works situate the Berlin Painter in context when the Persian Empire threatened to enslave Greece.

“He was not a rock star in his day, instead a humble craftsman, but his reputation among students of classical art has remained undiminished since his rediscovery a century ago. Pretty amazing for an artist whose real name we may never know,” said Padgett.

Most Athenian vase-painters did not sign their work, and so historical researchers have analyzed individual pieces to attribute to painters by their style. Sir John Beazley, the 20th-century Oxford scholar who made a major contribution to art history in his classification of Athenian vases, first identified works in collections around the world by this artist’s hand.

The Berlin Painter worked entirely in clay, and rendered fine details with dexterous precision in varying lines of black and reddish gold slip. He updated the conventional modes of his time by simplifying the designs on Greek vessels, having a major impact on other vase-painters of the period.

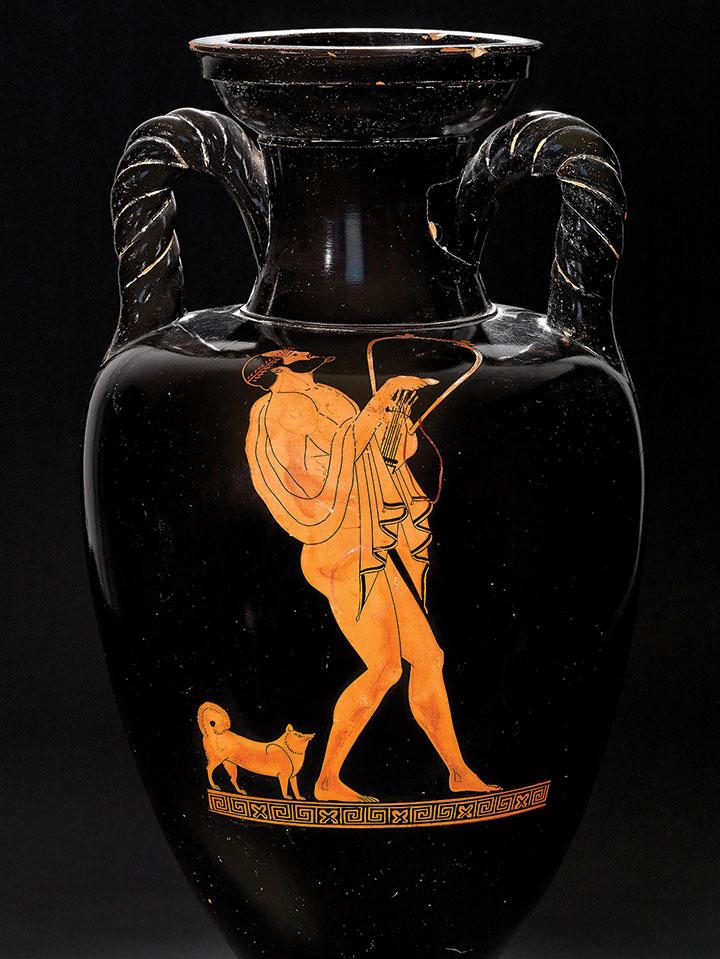

The show includes the vase featuring the god Hermes for which Beazley named the artist; it is on loan from the Antikenmuseum of the State Museums of Berlin. “The director, Andreas Scholl, looked at me over his glasses and said, ‘You know, we normally would never think of lending that vase, but for an exhibition devoted to the artist, well ...’ I knew then that we had a show,” Padgett said.

The exhibition features major loans from the Musée du Louvre in Paris and the British Museum in London, among others, as well as two objects from Princeton and pieces from the private collections of Gregory Callimanopulos ’57, who provided two vases, and Andrés Mata ’78, who lent a bronze statuette of the goddess Athena.

A Padgett favorite is an amphora with a young citharode — a singer accompanying himself on a lyre called a kithara — from New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art. The curator said the citharode seems “to float through an ether of glossy black, untethered and unframed, his head thrown back in song.”

Padgett and his colleagues spent three years assembling the exhibition, which is accompanied by a fully illustrated catalog. An international conference on Athenian vase-painting will be held on campus April 1. The show will move to the Toledo Museum of Art after its Princeton premiere.