You could forgive Will Dobbie, an assistant professor of economics and public affairs, if his work made him a bit glum. Not only is he a scholar of what’s been called “the dismal science,” his particular field of interest — public education — has stymied generations of policymakers. Now, with school-choice advocate Betsy DeVos heading the nation’s Department of Education, battles over schools and their funding seem likely to intensify.

But Dobbie is an optimist, working to find out what will improve schools in the country’s poorest areas. “The research community has made tremendous progress,” he says, “and now we’re thinking about whether short-term gains will translate into long-term gains. Then we’ll be able to take a serious step forward.”

In several papers written since 2011, Dobbie and collaborator Roland G. Fryer of Harvard University have been zeroing in on the characteristics of effective charter schools, publicly funded schools that operate independently. Strategies that work in charter schools — which can be easier to study than typical public schools — then can be implemented elsewhere, Dobbie says. The professors’ work also illustrates the great differences among charter schools, which often are portrayed as monolithic in discussions about school choice.

Dobbie and Fryer’s most recent working paper, released in July, explores how charter schools serving low-income Texas students affect test scores and — perhaps more important — earnings in a graduate’s early career, allowing students to move out of poverty. The researchers paid particular attention to so-called No Excuses schools, which generally have strict discipline codes, school-uniform requirements, and extended hours. If there were gains in test scores and wages, Dobbie theorized, this is where they’d be seen.

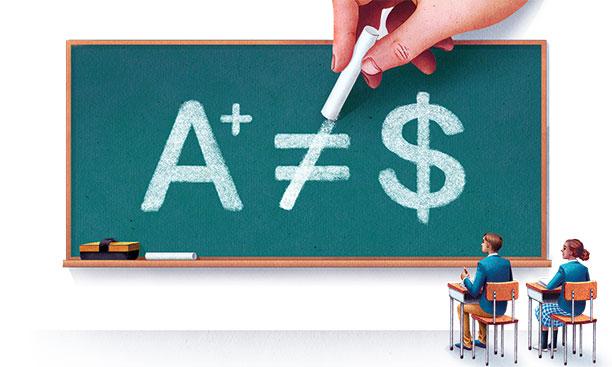

The two researchers found that No Excuses schools did indeed have higher test scores and higher rates of four-year college enrollment, but mustered only a small and statistically insignificant increase in earnings. And at other charter schools, test scores, four-year-college enrollment, and earnings all were depressed.

The researchers could not be certain what caused these results, Dobbie says. One possible explanation for the finding that even high-scoring charter schools do not have a clear impact on earnings is an overemphasis on test preparation at the expense of teaching skills needed for a good job. “Some argue that familiarity with a foreign language, adeptness with social studies, and immersion in the arts are important elements of a liberal-arts education that instill creativity, problem-solving skills, grit, and other non-cognitive skills that are important for labor-market success,” they write. “Others believe that these skills are essentially a ‘luxury good,’ and students (particularly those who are low-income) would be better served by focusing on basic math and reading.”

Their studies, Dobbie says, should help policymakers predict which schools will fail — and feel more confident in closing schools in which students fall behind and do not go on to higher education. Now their focus is on what predicts success: If higher test scores don’t lift wages, what will?