Maybe you and your roommates journeyed up to Harvard or Yale for football games during your college days. Maybe you never ventured far past FitzRandolph Gate. No matter. Throw your class jacket or Reunions costume in a suitcase. We’re taking a road trip.

Where are we headed?

To see Princeton, which means: everywhere. Ties to Old Nassau are all around us, if we only think to look. That’s to be expected for a 261-year-old institution that proclaims the motto “Princeton in the nation’s service and the service of humanity.”

With those words in mind and a travel itch to be scratched, I devised this plan: Build a cross-country road trip to every state in the Union, stopping only at Princeton-related sites: birthplaces, graves, famous homes, statues, historical markers, and any other oddity we can think of. We had to have at least one site in every state, although many states could boast a dozen. (I couldn’t visit every state on this trip, but those who can will find plenty of options.) You’ll see a shortened list surrounding this article; a longer one is available at paw.princeton.edu, and with your input we can expand it in the years to come.

Why undertake such an expedition?

As Norman Thomas 1905 once observed about Reunions, “Some things in life justify themselves emotionally, without necessity for analytic reasoning.” Let me suggest that the same spirit applies here. A good road trip, like life itself, is about the journey, not the destination.

But if fresh air and the open road aren’t enough for you, say that we’re taking this trip to show that it is possible. Some Princeton-related sites are known to all — the White House, anyone? — but many are less familiar, and a few may surprise you. The nation’s story and the University’s are intertwined, so if we can see how Princeton built America, perhaps we can also learn something about how America built Princeton. In these fractious political times, there may be something worthwhile in rediscovering our shared history.We’ll need a travel companion, of course. Let me introduce you to my classmate, Sev Onyshkevych ’83. Sev has been to 201 countries — including some that no longer exist — so 50 states would be a walk in the park, and he is a fount of Princeton lore. Best of all, he has an orange Lotus sports car, nicknamed the Pumpkin, to give our ceremonial send-off some pizzazz. You may have seen the Pumpkin in the P-rade once or twice. It’s an eye-catcher, capable of doing 100 mph as if it were in neutral. Hop in the back. Sure, it’s a two-seater, but you don’t take up much space.

Browse more than 300 Princeton-related sites around the United States

Before we set off, we had better define some terms. What qualifies as a Princeton connection? Any site associated with an undergraduate or graduate alum makes the list, but think broadly. Faculty members are included as well: They are also a critical part of Princeton’s story and have made seminal contributions to the country’s history.

So bring along a few issues of PAW to read, some Nassoons or Tigerlilies CDs for entertainment. Snacks? We can get them on the way, although we probably should pack a couple of gallons of Orange and Black Kool-Aid. We’ll be drinking a lot of it.

DAY 1 (Pennsylvania and Maryland)

We could stay in New Jersey all day and still not see everything Princeton-related, but let’s decree that our trip officially begins when we cross the Delaware River.

First stop: a pair of icons. There have been Princeton movie and television stars, from Josh Logan ’31 to Brooke Shields ’87 to Ellie Kemper ’02, but Jimmy Stewart ’32 beats them all. Thanks to classics such as It’s a Wonderful Life and Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, which practically define the country’s best sense of itself, he remains, two decades after his death, one of our most beloved actors.

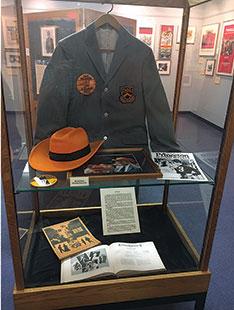

Stewart grew up in Indiana, Pa., about an hour’s drive west of Altoona. The Jimmy Stewart Museum, which opened in 1995 in the local library, has an impressive collection of Stewart-abilia, including his favorite booth from the Hollywood restaurant Chasen’s and the front door of his Hollywood home. One display particularly catches our eye: It contains Stewart’s Reunions jacket alongside a copy of the 1932 Bric-a-Brac and an issue of PAW with him on the cover.To a generation of sports fans, Hobey Baker 1914 was not just a star, but a romantic hero. He is the only person in both the college football and hockey halls of fame, and the award given annually to the best collegiate hockey player bears his name. All the biographies say that he was born in Bala Cynwyd, on Philadelphia’s Main Line, but that turns out not to be true. Hobey Baker spent the first eight years of his life in an unpretentious Philadelphia bungalow overlooking Wissahickon Creek. Most likely, he learned to skate there.

As evidence of his enduring fame as an athlete and World War I pilot, Baker’s grave, a few miles away in West Laurel Hill Cemetery, still draws admirers, many of whom decorate his headstone with hockey pucks. On the day we visit, there are more than half a dozen.Of course, Baker’s grave is only one of many athletics-related places to see on a cross-country Princeton tour. You know about the first intercollegiate football game, played at Rutgers in 1869 (a sign there marks the spot). Several colleges, including Oklahoma State and Idaho State, adopted our colors as their own. Ohio State nearly did, too, until students discovered that Princeton had already claimed them and so switched to scarlet and gray.

We’ve highlighted seven interesting stories off the beaten path

Halls of fame across the country, both college and professional, are full of distinguished Princeton athletes. To pick just one, we stop at the Lacrosse Hall of Fame in the town of Sparks, just north of Baltimore. Thirteen Tigers are enshrined there, and the playing field is named for former men’s coach Bill Tierney. Across the continent, at Nike’s headquarters in Beaverton, Ore., a bronze plaque honors Lynn Jennings ’83, perhaps the greatest American female distance runner.

What would a summer road trip be without a ballgame? Princeton’s ties to our national pastime run almost as deep as those to football. If you like some Old Nassau at the old ballgame, you might choose to cheer on the Cleveland Indians, whose general manager is Mike Chernoff ’03; or the St. Louis Cardinals, for whom Matt Bowman ’14 pitches; or perhaps the New York Mets, bought in 1980 by Nelson Doubleday ’55, who put the team on track to win the World Series six years later. Visit the Hall of Fame in Cooperstown, N.Y., and you can see a marker honoring former commissioner Bowie Kuhn ’48 and a catcher’s mask belonging to Moe Berg ’23, owner of a career .243 batting average, of whom it was said that he could speak seven languages and couldn’t hit in any of them.

Are you hungry? Don’t think we’ll stop finding Princeton ties at the concession stand. Andrew “Butch” Armour ’33, scion of the hot-dog family, dropped out after his junior year but gave almost $6 million to the University. As for beer, well, we have that market cornered with names like Molson, Stroh, Yuengling, and Coors in our alumni ranks. Prescott Pabst Wurlitzer ’72 came from both the beer and electric-organ families and thus was practically a night at the ballpark all by himself.

DAY 2 (Washington, D.C., and Virginia)

University connections in our nation’s capital are so thick we can practically trip over them. Besides the obvious ones — the presidents, Supreme Court justices, Cabinet officers, members of Congress, and former first lady Michelle Obama ’85 — Princetonians have been a presence in virtually every government building. Paul Volcker ’49 and former economics professor Ben Bernanke chaired the Federal Reserve. Allen Dulles 1914 *1916 was CIA director during the depths of the Cold War. There is a bust of his older brother, John Foster Dulles 1908, one of eight alumni former secretaries of state, at the airport named for him in northern Virginia.

Many alumni distinguished themselves defending the country, and markers of their service dot the national map. You can see the grave of Admiral William Crowe Jr. *65, who chaired the Joint Chiefs of Staff, at the Naval Academy in Annapolis. Edwards Air Force Base in California is named for Glen Edwards *47, a test pilot and one of the first recipients of a graduate degree in aeronautical engineering.

Eight alumni and one professor have been awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor, but only two received the medal for actions on American soil. The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House, Va., in May 1864 is remembered for the obscene carnage at the Bloody Angle, but only a mile or so away, Brig. Gen. Charles Phelps 1852 of the Maryland militia led a heroic Union charge. He almost overran the Confederate lines before he was wounded and captured. A stone obelisk deep in the woods marks the spot where Phelps fell, and reads in part, “Never mind cannon, Never mind bullets, Press on and clear this road.” It is so hard to find that I doubt a dozen people see it in a decade.

The second domestic Medal of Honor recipient is less remembered, perhaps deservedly so. Albert McMillan 1884 rode with the Army’s 7th Cavalry — formerly George Custer’s unit — at the Battle of Wounded Knee in 1890 in which federal troops massacred 150 Sioux, including many women and children. The South is dotted with former slave plantations owned by Princeton graduates, and scores fought for the Confederacy during the Civil War.

Though it hardly atones for the sin of slavery, a plaque outside Foster Auditorium at the University of Alabama marks the spot where Deputy Attorney General Nicholas Katzenbach ’43 faced down Gov. George Wallace in the battle to integrate that school in September 1963. In federal courthouses in Alabama and Mississippi, John Doar ’44, chief lawyer for the Justice Department’s civil-rights division, prosecuted the murders of civil-rights workers.

DAY 3 (Central Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois)

You know who wouldn’t have liked a road trip? James Madison 1771. At least we know that he wouldn’t have approved of the road itself — specifically, the National Road, now part of U.S. Route 40, which runs from Cumberland, Md., to Vandalia, Ill. In 1817, Congress passed an appropriations bill providing money for it, which Madison vetoed on the grounds that Congress’ enumerated powers did not extend to constructing roads or canals. “I am constrained by the insuperable difficulty I feel in reconciling the bill with the Constitution,” scolded the man who wrote the Constitution. No National Road, no interstate highway system, no road trip. Fortunately for us (depending on your point of view), Madison’s successors were less scrupulous about federal infrastructure projects.

I can’t think of any roads built by Princetonians, but they have made planes (James Smith McDonnell 1921 founded what is now McDonnell Douglas), trains (lots of railroad connections), and automobiles (William Clay Ford ’79, executive chairman of Ford Motor Co.), not to mention tires (Harvey Firestone was a Princeton parent), and gasoline (Rockefellers). If you would rather travel by sea, there have been several USS Princetons; the current one is based in San Diego.

Ours is hardly the first Princeton road trip, of course. In the summer of 1921, three undergraduates — Edward Conover 1921, Gordon Curtis 1921, and his brother, B. Strang Curtis 1922 — drove 11,455 miles to the West Coast and back (they took the scenic route), compiling a fascinating scrapbook of their adventures that resides in Mudd Library. Pete Conrad ’53 took the longest “road trip” in November 1969 when he went to the moon as commander of the Apollo 12 mission and carried with him a Princeton flag, now on loan to the Museum of Flight in Seattle.

Woodrow Wilson 1879 barnstormed the country in 1919 to whip up support for U.S. entry into the League of Nations, covering more than 8,000 miles in 22 days. He delivered scores of speeches, including the last one of his career, on Sept. 25, 1919, in the municipal auditorium in Pueblo, Colo., as a bronze marker in the lobby attests. Wilson took ill that night and suffered a crippling stroke seven days later.

F. Scott Fitzgerald 1917 and his wife, Zelda, once traveled from their home in Connecticut to visit Zelda’s parents in Alabama, a road trip he recounted in The Cruise of the Rolling Junk. The “Rolling Junk” was the name given to their car, a 1918 Marmon, which he also dubbed “The Expenso” because of its predilection for breaking down. It’s a rollicking story, but all the big magazines turned it down, and he eventually serialized it in Motor magazine for just $300. Only recently has it been released as a novella.

“To be young,” Fitzgerald wrote on their first day away from home, “to be bound for the far hills, to be going where happiness hung from a tree, a ring to be tilted for, a bright garland to be won — It was still a realizable thing, we thought, still a harbor from the dullness and the tears and the disillusion of all the stationary world.” Now there was a man who enjoyed a road trip. Zelda, of course, felt differently. “The joys of motoring are more or less fictional,” she wrote to a friend.

Speaking of Fitzgerald, it is possible to take a cross-country road trip stopping only at Fitzgerald-related sites, including his grave in Rockville, Md., where pilgrims leave pens. Other Princetonians are equally ubiquitous. Wilson was born in Staunton, Va., but one can visit homes he lived in or visited in Chillicothe, Ohio; Augusta, Ga.; Swarthmore, Pa.; Wilmington, N.C.; and Washington, D.C. Illinois, meanwhile, practically bulges with sites related to Adlai Stevenson 1922, who served as the state’s governor before his two presidential runs. At Stevenson’s home in Libertyville, his study is preserved just as he left it. We drive a few miles south and take a section of I-55 — known as the Adlai Stevenson Expressway — into Chicago.DAY 4 (Chicago)

All this history is fine, but the essence of a good road trip is people. That is what brings us to Table, Donkey and Stick, Matt Sussman ’09’s wonderful restaurant in Chicago’s Logan Square neighborhood. He took the name from a Brothers Grimm fairy tale.

Many alumni groups consider themselves rabid, but the Princeton Club of Chicago — one of the oldest alumni clubs outside New York — takes the cake (or, given Sussman’s menu, the charcuterie). Nine members are meeting us for dinner, a mixed group spread in age across five decades. For us, it’s a chance to introduce ourselves; for them, a chance to reconnect. Former president Rob Khoury ’90 tells me about events the club hosts for the more than 2,000 alumni who live in the Chicago area, ranging from lectures to Cubs games to a movie night in Millennium Park. We refrain from singing “Old Nassau” or raising a locomotive cheer, but no such gathering would be complete without a group photo for PAW (see below). There are a host of alumni-owned restaurants, inns, bed and breakfasts, breweries, and vineyards around the country to welcome a weary traveler far from campus.

Let’s turn south now, passing up a chance to see Madison, Wis., the largest city named for a Princetonian. However, don’t overlook Dayton, Ohio (named for Jonathan Dayton 1776), or Macon, Ga.(named for U.S. senator Nathaniel Macon, who attended Princeton in the 1780s). Many think that Dallas, Texas is named for George Mifflin Dallas 1810, James Polk’s vice president. It isn’t — although Dallas County, which surrounds it, probably is.

Ken Perry ’50, a man after my own heart, has been to all 32 Princetons, had breakfast in each one (or tried to), and wrote a book about it, Breakfast in Princeton, USA. When asked why he did it, Perry paraphrases former basketball coach Pete Carril: “What fun is it to be a Princetonian and not visit Princetons?” His wife, Garie, who accompanied him, explains it even better. She says, “Follow your bliss.”

DAY 5 (St. Louis)

It’s a big country, so this city on the banks of the Mississippi River, the Gateway to the West, is as far as we can go on this trip. Our list is ever expanding, though, so there are many more sites to see later. Please make your own Princeton road trip and write to paw@princeton.edu to tell us what we missed in ours.

St. Louis has many Princeton connections, including another vibrant alumni club and the beautiful Washington University campus, much of which is named for its longtime chancellor, William H. Danforth ’48. It also boasts the John C. Danforth [’58] Center on Religion and Politics, named for his brother, the former U.S. senator. Another former senator, Bill Bradley ’65 — how could we leave him out? — grew up in Crystal City, Mo., just a few dozen miles south.

If Brookings Hall, Wash U’s main administrative building, looks like a dead ringer for Blair Arch, that’s because it is. It was built in 1902, six years after Blair, by the same architects, Cope & Stewardson. Travel the country and you will often experience Princeton déjà vu. Duke University and many others adopted the same collegiate-gothic style. Frank Gehry designed Princeton’s Lewis Science Library on Washington Road as well as the Peter B. Lewis [’55] Building, a near-copy, at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland. You’ll find copies of Henry Moore’s sculpture “Oval with Points” as far away as Hong Kong.

Before we let Sev go home and the Pumpkin turns back into, well, a pumpkin, let’s take the elevator to the top of the Gateway Arch for a breathtaking view of the St. Louis skyline at dusk. Built in 1965, the arch is the masterpiece of Finnish architect Eero Saarinen, who never designed a building at Princeton, although his Brutalist style influenced the now-razed New New Quad.

A park ranger says we can see for 30 miles, but it seems much farther than that. It’s almost as though we can see over the horizon, into “that vast obscurity beyond the city,” as Fitzgerald wrote in The Great Gatsby, “where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.”

Looking west, I recall the teams of Princeton faculty and students who went on groundbreaking expeditions to Colorado, Wyoming, and Utah nearly every summer during the late 19th century, unearthing dinosaur fossils and revolutionizing the field of paleontology. Henry Fairfield Osborn, William Berryman Scott, and Francis Speir Jr. — all of the Class of 1877 — are little remembered today outside of their field, but they were pioneers.

Princeton discontinued its paleontology program in 1985 and sold its extensive fossil collection to Yale. One of the most interesting Princeton-related discoveries, though, resides at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, which we will see on our return trip. An expedition to Wyoming in 1899 brought back the bones of the largest dinosaur ever discovered. John Bell Hatcher, the museum’s curator and a former Princeton professor, named it Diplodocus carnegii, after industrialist Andrew Carnegie, who financed the expedition. The bones are on display inside, while a life-size fiberglass model of the dinosaur, known as “Dippy,” looms over Forbes Avenue outside.

Now, at the arch, I imagine that we can see out to those dinosaur fields; to Mount Princeton in Colorado; to Goldfield, Nev., where Johnny Poe 1895 worked as a watchman before going off to fight somewhere as a mercenary; to the Arizona copper mines that made Cleveland Dodge 1879 the fortune he used to build Dodge-Osborn Hall. Look hard and you might see out to the Pacific coast, where Jimmy Stewart made his movies. Who knows? With a strong-enough telescope, perhaps we could still make out Pete Conrad’s footprints on the moon.

Gazing west across the continent, it’s the setting sun that is most affecting, that flaming ball poised just above the darkening city. Have you ever seen colors like that? It’s almost impossible to describe them. What are they?

From my vantage point, I’d have to say orange and black.

Mark F. Bernstein ’83 is PAW’s senior writer. To suggest a site for inclusion in our list of Princeton-related places, post a comment below or write to paw@princeton.edu.