The artifacts of activism at Princeton come in many forms: membership cards for the Veterans of Future Wars, a satirical student group that made national headlines in 1936; audio cassettes from WPRB’s coverage of a campus meeting at Jadwin Gym during the May 1970 strike that followed the U.S. invasion of Cambodia; and scores of photos, mostly black-and-white, from public demonstrations such as the 1978 occupation of Nassau Hall, when students protested University investments in companies doing business in apartheid-era South Africa.

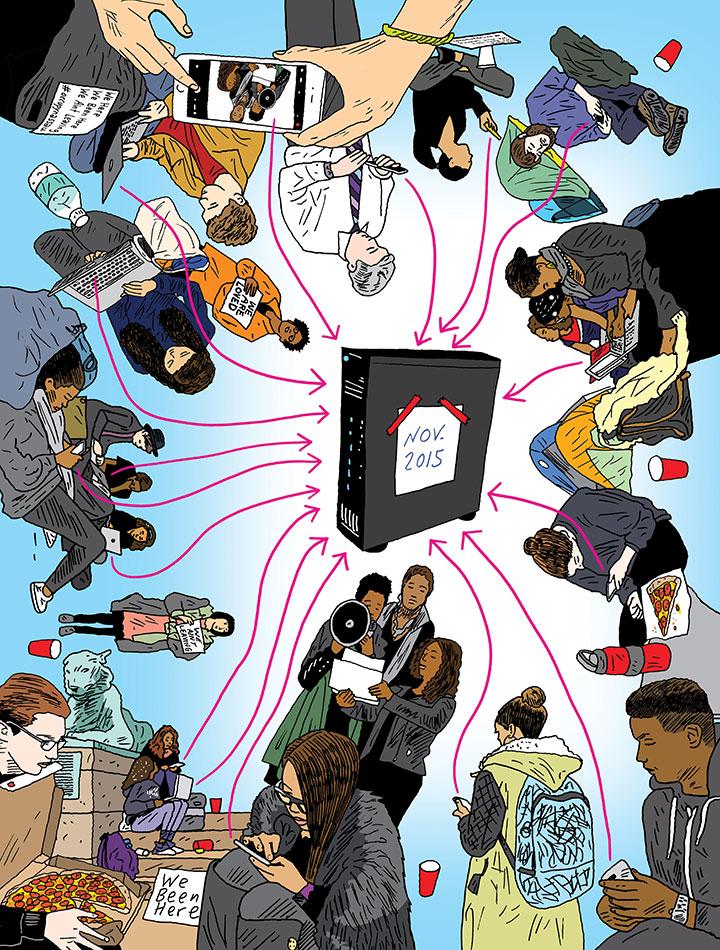

During the 2015 Nassau Hall sit-in — the protest that sparked a re-examination of Woodrow Wilson 1879’s legacy and a broader discussion of diversity and inclusion at Princeton — archivists knew they would need to take a different approach, one not dependent on file boxes.

“As it was happening, we said, ‘This is certainly something we want to capture,’” says University Archivist Daniel Linke. “We’re no longer in a paper-based environment, especially with students. So the question was: How do we capture this moment?”

Two weeks after the sit-in began, Jarrett Drake, then the digital archivist at the Mudd Manuscript Library, announced the start of ASAP: Archiving Student Activism at Princeton, a proactive effort to collect artifacts from the demonstrations and the broader range of advocacy on campus. The archival record was destined to be digital: Explore the University Archives online today and you can find, for example, the Princeton Black Justice League’s Medium.com post, “An Open Letter On Free Speech, Our Demands, and Civil Disruption,” or its Change.org petition, signed by more than 1,000 supporters (both included in the Black Justice League records). You can also read a timeline of the 33-hour sit-in on the University Press Club’s Twitter feed, with updates filed from inside President Eisgruber ’83’s office (part of the Princeton University Publications Collection).

While digital archiving was nothing new for Linke and his colleagues at Mudd, the exercise of capturing recent history and preserving it in its “born-digital” formats proved fruitful, eventually inspiring the addition of a staff position devoted to archiving student life. Valencia Johnson, who started in the role in early March, has spent much of the last two months on outreach, meeting with the departments that interact with students and encouraging student organizations to maintain and preserve their records. In speaking with students, she stresses that Mudd is not merely a place to find research materials, but also a place to give them. Making a donation to the archives can be as simple as sharing a link to your student organization’s Google Drive folder.

“You learn so much outside the classroom — you’re building relationships, you’re being challenged on your opinions, you’re growing as a person,” Johnson says. “University archives are beginning to do a better job of making sure that we’re capturing that life outside of academia.”

Digital accessions — photos, videos, documents, emails, websites, class-reunion books on DVD — are rapidly expanding Mudd’s virtual shelves, and not just in the realm of student life. In the University archives and public-policy papers, about 120 collections include born-digital materials, taking up about 3 terabytes of storage (a modest footprint by archival standards).

Why has student life become a priority? For archivists, it is important to capture these records before they disappear. “Because it’s so easy to create content in the digital age, people often don’t think about it as something to preserve,” says Annalise Berdini, Mudd’s digital archivist. “They don’t think about it as something that’s a form of record.”

In a more paper-based era, Linke adds, alumni might keep a box of clippings or files in their basement and eventually donate it to the archives 20 or 30 years after they graduate. But the future of electronic records seems less certain. “Thirty years from now, will any of the student organizations have the equivalent of the box in the basement?” Linke asks. “Will they still have their same Gmail account? Will Gmail exist?”

Working with students helps the archivists, according to Alexis Antracoli, the assistant university archivist for technical services, because students tend to be in tune with digital trends. That keeps archivists thinking about the challenges to come.

Like many of her colleagues at Mudd, Antracoli was a historian before she became an archivist. When she started working in archives, she envisioned processing early American manuscripts. Instead, she immersed herself in electronic-records projects and found a niche on the digital side.

Antracoli became enamored with the benefits that digital archives would have for researchers, particularly those who aren’t scholars or historians with the means to travel to wherever a collection resides. “I’m really passionate about the idea that archives are for everyone, whether you’re doing genealogy or a high school research project or the history of your community,” she says. “I want our materials to be as widely accessible to people as possible, in ways that are meaningful for them.”

Digital collections lend themselves to that “multiplicity of uses,” says Linke, who notes that the digital age has reshaped some of Mudd’s traditional accessions, particularly those that come from University offices.

The records of past deans rely heavily on correspondence, which has moved from filing cabinets to email folders. In the long term, the digital files could be helpful because they’d allow for big-data text analyses on large collections of email, Linke says. On the acquisition side, however, dealing with the volume of email requires sorting and culling. When Valerie Smith left her post as Princeton’s dean of the College to become the president of Swarthmore College, she had nearly 100,000 messages in her email account. Linke and Drake worked with Smith’s office to narrow the list of correspondents and identify messages that contained important keywords in the subject lines. Their work yielded just over 20,000 emails — about 5,000 sent and 15,000 received — that will be preserved in the University Archives.

Linke does not advise administrators about email preservation in advance, but the University’s records-management principles encourage retaining “records with potential historical value to the University.”

As offices have gone digital, so have student records. When an undergraduate class passes through FitzRandolph Gate each June, the academic files of the new grads are sent to be stored at Mudd. One class used to fill about 40 boxes of paper. But the Class of 2017 version arrived in a significantly smaller package: a single encrypted hard drive, filled with PDF documents.

For the average computer user, this all sounds blissfully simple. Drag-and-drop archiving — how hard could it be? But archivists have to consider users far into the future. An email created in Outlook, Microsoft’s proprietary format, may not be readable in 40 years, when a retired dean’s files are opened to researchers. Archivists prefer formats that can be read by multiple programs, such as PDFs and JPEGs. But if you convert each message to a PDF, you also need to include PDFs of the message’s attachments. And the act of opening that attachment to convert it could inadvertently change metadata (the date it was last revised, for example) that future researchers might find valuable.

In a way, paper was easier: You don’t need the right application to open a letter.

To deal with this digital challenge, Princeton archivists rely on FRED — a Forensic Recovery of Evidence Device — a tool developed for the law-enforcement community to preserve files used in investigations. The FRED looks like a large computer stack, with a quantity and variety of input jacks so expansive that one can hardly imagine using half of them. When archivists connect the source media — a hard drive, for example — to the FRED, it creates bit-for-bit copies of the files without altering their metadata. That becomes the master preservation copy, should anything happen to the file when it’s processed or stored. Archivists use the computer to scan for personally identifiable information, such as Social Security numbers, so that they can be redacted from publicly accessible files. The FRED also generates “checksum” records, a sort of digital fingerprint that can be used later to detect when a file is corrupted (or in a courtroom setting, to certify that a file hasn’t been tampered with).

In addition to its use at the University Archives, the FRED has proven helpful in the library’s Manuscripts Division, headed by longtime curator Don Skemer. When archivists were processing the papers of Nobel laureate Toni Morrison, they came across floppy disks that contained some of her drafts, including versions of her 1987 novel, Beloved.

Extracting the files did not yield much new material, Skemer says, because Morrison’s papers already included publisher’s proofs from that time. (Visitors to the collection are more interested in the author’s decidedly analog early drafts, written on yellow legal pads.) But the exercise did help to define a process for handling legacy-media materials, which archivists can now apply in other collections, including the papers of Argentine author and former Princeton professor Ricardo Piglia and American poet Alicia Ostriker. Skemer sees digital processing as a selling point for the Princeton libraries: “We can deal with your old media, even if you can’t.”

Extracting and reading documents from a 5 1/4-inch floppy disk may be old hat now, but there are other challenges related to digital files. For example, there’s the threat of bit-rot, or data-rot — the electric charge in one bit flips, and a file on a user-generated CD or DVD suddenly becomes corrupted. You might think those family photos are safe forever on a memory card, but without monitoring and backing up files, “all of it degrades eventually,” says digital archivist Berdini. “That’s the biggest misconception people have about digital content.”

Princeton has processes in place to create and store copies and backups on more stable media. But that’s just for the files donated to its collections. What about content that’s online, on the hundreds of websites for University departments and organizations? Since 2015, archivists have been using Archive-It, a service developed by the Internet Archive, to preserve periodic copies of Princeton websites and social-media feeds. There are 130 sites currently included.

READ MORE Your Very Own Archive: Digital preservation tips from Mudd’s archivists

Princeton’s senior-thesis catalog also resides online now, with theses from the Class of 2013 forward available to on-campus users in PDF form. Linke said that when the University decided to store theses electronically, he expected to see an increase in the use of theses for student research, but even he was surprised by the magnitude — an eight-fold jump, from about 1,000 paper theses viewed in the year before the switch to just shy of 9,000 downloads in the third year after. That number continues to grow, with about 16,000 downloads, across all departments, in 2016–17. “We collect theses for the pedagogical use of students — it serves the educational purpose of Princeton’s hallmark academic requirement,” Linke says. “We’re better able to serve the student body, which isn’t necessarily going to come to Mudd Monday to Friday, 9 to 5. They can [read theses] at any time convenient to them.” Princeton graduate dissertations dating back to 2004 are available digitally, and some dissertations that were archived on microfilm have been digitized as well, by a third-party dissertation database.

Digital collections can be processed quickly in many cases. New additions at Mudd include the Princeton Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer/Questioning, Intersex, Asexual (LGBTQIA) Oral History Project, a series of transcripts and audio files recorded last summer. The first 15 interviews went online in October, and another 15 were published in March. Born-digital content provides updates for one of the University Archives’ most popular online collections, the digitized version of The Daily Princetonian (available at theprince.princeton.edu). Editors send PDF versions of the newspaper’s published editions, to be added to a scanned database that dates back to 1876.

The Daily Princetonian project has led some Mudd enthusiasts to look for a future when all collections are available online, but Linke is skeptical of that notion. “Not in my tenure,” he says. To date, about 2 million documents have been digitized — from a corpus of about 200 million.

Beyond the sheer bulk of material in storage, there is the question of how best to regulate access, which is a work in progress. “Electronic records are so easily shared, but you want to be able to share things according to various parameters,” Linke says. Some files may be protected by copyright, such as the Manuscript Division’s digitized audio interviews featuring some of Latin America’s most celebrated contemporary authors; others contain information that archivists would not want to freely share online for fear of data-mining — the shelves of class-reunion books come to mind.

The shift to digital also raises a nostalgic question: Is something lost when you’re no longer able to hold a physical document, to see the impressions made by the typewriter or the marginalia scrawled in red ink?

Linke points to a recent born-digital collection that he accepted for Mudd’s public-policy holdings: the papers of economics and public affairs professor Alan Krueger, a former chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers under President Barack Obama. While reviewing the files, which will remain closed until the Obama administration’s records are made public, Linke came across a folder labeled “POTUS” and discovered sets of PowerPoint slides from Krueger’s presidential briefings. He paged through, imagining the context in which they were first shared.

“It may have been electronic,” Linke says, “but this is what the president saw. That’s kind of cool. So there’s still a kind of ‘gee whiz’ moment when you’re dealing with records that have historical import.”

Brett Tomlinson is PAW’s digital editor.