Princeton bided its time as other universities expanded into China — some going so far as to establish degree-granting branch campuses open to Chinese students — but the University now is making its move, modest by some measures: It plans to rent 1,300 square feet of space on the campus of Tsinghua University, in Beijing, which will serve as a base of operations in that country.

The center, with a staff of two, will help visiting professors and students with logistical needs such as securing translators, finding housing, and generally making their way in China. It also will help Chinese scholars who need help interacting with Princeton.

A number of Princeton departments and programs already have strong ties to Chinese institutions including Tsinghua University, Peking University, Beijing Normal University, and Fudan University (in Shanghai). The new office is designed to supplement those connections, said history professor Jeremy Adelman, director of the University’s Council for International Teaching and Research.

Princeton has especially strong ties with Tsinghua University, where the dean of the school of life sciences, Yigong Shi, is a former Princeton professor of molecular biology. Princeton studied the approaches of other universities carefully before making its decision, and its approach stands in marked contrast with that of Stanford, for example, which built a $7 million, 36,000-square-foot center in a traditionalist Chinese-architectural style on the campus of Peking University.

Advancing the Tsinghua center was one of the goals of the Princeton delegation traveling with President Eisgruber ’83 on his Asia tour last month, which included stops in Beijing, Tokyo, Seoul, and Hong Kong.

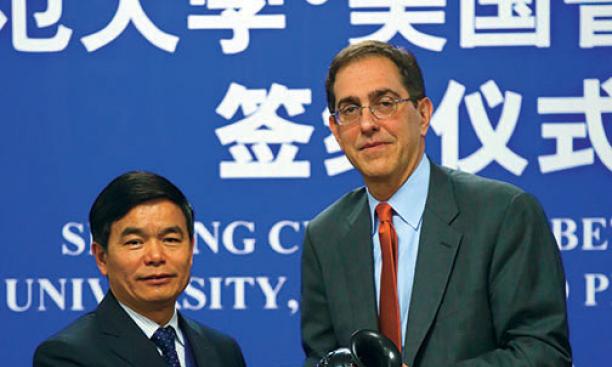

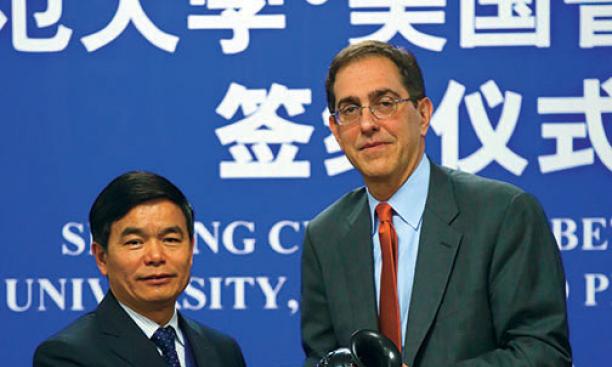

In Beijing, Eisgruber also signed an agreement with Beijing Normal University, site of the Princeton in Beijing summer-language program, to create a separate, full-fledged study-abroad program on that campus, extending through the academic year. The details remain to be worked out, although intense language instruction would be combined with courses taught in English. It would be open to both Princeton and non-Princeton students.

Princeton’s expansion into China comes at a time of renewed concern over Chinese interference in academic freedom. In October, Peking University fired a professor of economics, Xia Yeliang, because — or so he and many believe — he has written in favor of democratic reform. (Peking University officials said it’s because of subpar teaching.) More than 125 faculty members at Wellesley College appealed to their administration, in an open letter, to consider ending a formal exchange program with the institution.

“The big problem with all of these exchanges is that they accept engagement over everything, without drawing any lines,” said Thomas Cushman, a sociology professor at Wellesley. What those lines should be ought to be open to debate, he said, “but nobody is having that discussion.”

Perry Link, a professor emeritus of East Asian studies at Princeton who is now at the University of California at Riverside, called the Wellesley faculty protest a “terrific” development. Forbidden to enter China since 1996, he has been critical of Princeton for not speaking out more forcefully on behalf of him and other blacklisted scholars. Gilbert Rozman, professor emeritus of sociology, was denied entry to China just this fall — perhaps, he said, because he once attended a meeting of scholars planning to study the Uyghur ethnic group, though he himself never wrote on the subject.

Several Princeton professors with close connections in China expressed little interest in a grass-roots movement to challenge Chinese censorship or blacklisting. Gang Tian, a Princeton math professor who also runs the Beijing International Center for Mathematical Research at Peking University, said that “we have never had a problem” with political meddling and that Peking University “is very supportive.”

Upon his return to campus Nov. 6, in response to questions from PAW, Eisgruber said in a statement that he had raised the issue of Xia Yeliang’s firing in a meeting with the president of Peking University, Wang Enge. “I affirmed Princeton’s strong support for principles of academic freedom,” Eisgruber wrote. “I also observed that respect for those principles would be important to the success of collaborations between American and Chinese universities.” Wang, he said, reiterated the argument that the economist’s loss of his job was unrelated to politics.

“Whether or not one accepts that argument, Princeton will have to be vigilant to ensure the academic integrity of its projects in China,” Eisgruber wrote. “But I firmly believe that, for those of us who care about academic freedom and the benefits that higher education brings to a society, constructive engagement with Chinese universities is far more salutary than withdrawal.”

The small scale of Princeton’s Beijing office may allow more flexibility to respond to political developments in China than other universities have, said Diana Davies, vice provost for international initiatives: “If the political system became more repressive, we are not so deeply sunk that we would not be able to leave.”