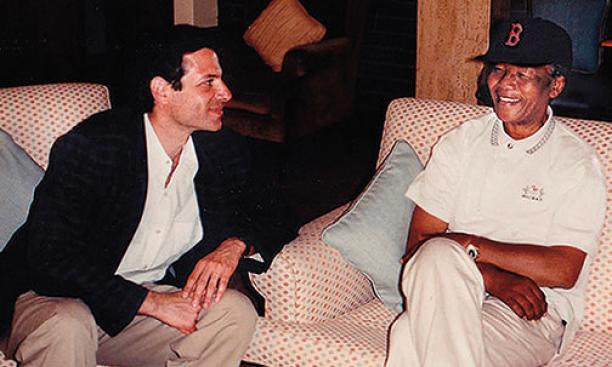

A journalist, Richard Stengel ’77 spent many years working on one particular story: South African president Nelson Mandela, who died in December at 95. Stengel ghostwrote Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela’s 1993 memoir, and wrote two other volumes about Mandela and South Africa. The former managing editor at Time magazine, Stengel has been nominated by President Obama to become undersecretary for public diplomacy and public affairs at the State Department. He spoke with PAW after Mandela’s death.

How did you first connect with Mandela?

I had gone to South Africa in the mid-1980s for a freelance assignment for Rolling Stone magazine. I did a piece for them about life in a little town where there was a forced removal going on — moving black residents out of the town. I wrote a book about it, January Sun: One Day, Three Lives, A South African Town. When Little, Brown signed up Mandela for an autobiography, the editor read my book and hired me to work as a ghostwriter. I met Mandela for the first time when I went to South Africa in December 1992.

How often did you meet with him?

For most of 1993, I would meet with him several times a week, usually early in the morning, to get him talking about his life. I also asked if I could just hang around with him. We hit it off.

What was he like?

He was very sunny. He had a lovely sense of humor. When Mandela went into prison, he was known as a hotheaded firebrand — not someone we would recognize today. Prison taught him self-control. He was a terribly early riser. Mandela had not spent much time around Americans, so I became like an ambassador for the U.S., a proxy for him. I remember one morning starting at 4:30 a.m. We met at his house in the Transkei, and I was bedraggled when I showed up. He said, “You don’t look like a superpower!”

You’ve suggested that he was not especially sentimental or spiritual.

He was a hard man, which is something that gets lost in all of the beatification. He was a revolutionary. He made many hard choices in his life. As the saying goes, he had a nice smile but iron teeth.

How bad were the conditions in prison?

At first, he didn’t have much freedom of movement and he couldn’t talk back to the jailers, because if you talked back, you’d get a beating. That gave him self-discipline. He lived in a tiny cell. When I first went to Robben Island and saw it, I gasped, because he was 6-foot-2, with broad shoulders and a big head, and his cell was like a shoebox. Everything in his cell was meticulously organized. There were records of everything — little diaries of what he had eaten, how many sit-ups and push-ups he did.

Eventually during his imprisonment, people knew he was going to be a great leader. So probably for the last 10 years in prison he was treated more delicately. But for the first few years it was very tough.

How does he compare with Gandhi and Martin Luther King?

The person I liken him to more is George Washington. He was the father of his country, and everything he did was a prototype for what followed. One of Mandela’s most important decisions was to serve one term, even though he could have been president for life. George Washington did much the same when he stepped down after two terms. Gandhi and King were apostles of nonviolence — it was intrinsic to their philosophy. That was not the case with Mandela. For him, nonviolence was a tactic, not a principle.

To what extent have his successors lived up to his ideals?

It’s hard to live up to the model of Nelson Mandela. He put the country on the road to being a successful, nonracial, capitalist democracy. And I think people in South Africa feel like they are a young nation with a tremendous amount of potential. It has lots of problems, but I think Mandela set them up with a very solid foundation.

Interview conducted and condensed by Louis Jacobson ’92