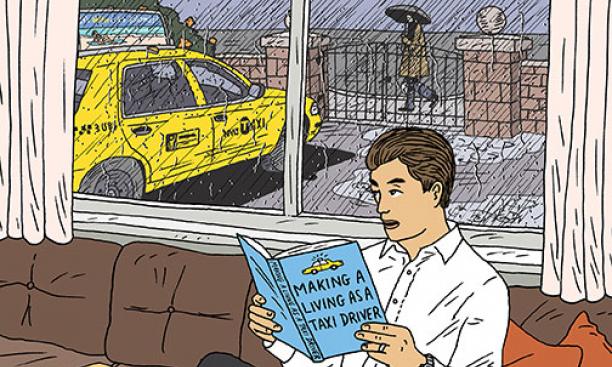

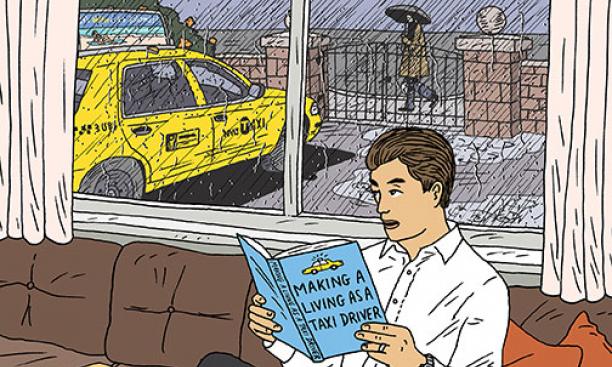

Most of us have been there, standing in the rain on a street corner as a stream of taxicabs rolls by, all of them occupied. Why, we wonder, is it so much harder to find a cab when it’s raining? Economics professor Henry Farber thinks he knows the reason.

Farber, who studies employment, thought that taxi drivers, who have a greater ability than most workers to set their own hours, would provide a good laboratory for examining how workers respond to earnings incentives. Farber obtained records of every cab ride taken in New York City between 2009 and 2013, a database of more than 700 million trips involving some 62,000 drivers, and combined some of that data with information about the weather.

When it rains, the data confirmed, the demand for cabs rises and the supply falls. One possible explanation of the drivers’ behavior is that workers begin each day with an earnings target in mind and stop when they reach that figure. On rainy days, according to this theory, drivers would reach their earnings goal sooner and quit earlier, thus taking cabs off the street. But Farber’s study revealed that drivers’ average hourly income is consistent, regardless of the weather. Drivers have an easier time finding passengers when it is raining, but it takes longer to reach their destinations. And since earnings are tied in large part to miles traveled, the gains drivers normally would enjoy from increased demand are offset by the longer driving times.

Farber found that the number of cabs on the street is about 7.1 percent lower when it is raining. “Some drivers stop, but this is not due to their reaching their income target,” he wrote. He speculates they stop working because they do not want to contend with the sloppy conditions and congested streets, all for the same average earnings they can make under good conditions: “Some drivers stop simply because it is less pleasant to drive in the rain and there is no additional benefit in continuing to drive.”

Driving a cab is a hard way to earn a living, and those who do it learn quickly how to work most efficiently, Farber says. When they can’t make a lot of money, smart drivers will choose to take a break or go home early; during periods when they can make more money, smart drivers will work longer. His findings tell us something about the way workers in other industries respond to earnings incentives. Unless their short-term wage rate goes up, they won’t work more.

Farber suggests that premium pricing might help alleviate the rainy-day shortage. Private ride-sharing services already charge higher rates during periods of greater demand, a tactic that is designed to increase the supply of drivers. Farber suggests that if municipal cab companies emulated this model, more drivers would hit the roads on rainy days, and we wouldn’t be left on a wet street corner, fruitlessly waving our arms for a taxi.

Until that happens, what advice would Farber give on a rainy day? “Get an umbrella and walk.”

Kahneman Sums Up A Lifetime Spent Probing How We Think

Eisgruber Picks Labor Economist Lee *96 *99 as Provost