Eddie S. Glaude Jr. *97 is the William S. Tod Professor of Religion and African American Studies and chairman of the Center for African American Studies at Princeton. The following essay is adapted from an address he gave at the conference for black alumni, “Coming Back and Moving Forward,” in October.

The great pragmatic sociologist George Herbert Mead understood the past as a condition of the present — without it, we lose our temporal bearing in the moment we occupy. We understand where we are, the things we care about, and the lives we live in light of the “doings and sufferings” of others who came before us. But, for Mead, there are moments in the present — the emergence of novelty — that do not follow from the past; “the past relative to which it was novel cannot be made to contain it.” For the present, Mead argues, there is always a past, and in those moments when true novelty emerges and our current story cannot account for it, we then must tell ourselves a story that will. The past will vary as the present varies. How, then, do we account for those moments that fundamentally reorder how we understand ourselves and the world we inhabit? We return to the past — to the archive — to that which “marks out and in a sense selects what has made [the peculiarity of the new] possible.”

We find ourselves in this momentous present, as American citizens — the beneficiaries of a grand, but deeply flawed experiment in democracy — confronting the novel in the form of our first African-American president. And, as a nation, we are struggling to account for his emergence and the significance of his presence to our national self-conception. We manically return to the archive, searching desperately our national past to make “sense of and to select what has made this peculiarity possible.” Some find resources for this effort in our national myth: We are, after all, the shining city on the hill, the Redeemer Nation, a nation with a divine calling to be a beacon light unto the world. President Obama’s election further solidifies, at least for some, this self-imagining.

Others appeal to a progressive understanding of American history: Though we have fallen short in relation to our stated principles, we, as a people, always are striving toward a more perfected union. Wrongs are realized and righted. That realization and correction confirm our inevitable end: a perfect union. So slavery’s stain is no more; women’s marginalization no more; Jim Crow no more — all in the forward march to the end that we are destined to reach. Still others find no need to appeal to history at all. America, they might say, never has been bound by the past; it is a nation predicated on an open-ended future. President Obama exemplifies this fact. We have no need, they might argue, to be concerned about the problems of the past; his election announces that we have removed the burdens of old only to embrace the possibilities of now and of the future.

Each of these approaches should sound familiar, because they have provided a framework for our national history as it is. But the underlying challenge here, what makes this effort so charged with the emotion of uncertainty, is that this man — this particular body — brings into view those experiences of a people who have called into question the very premises of the story we have told ourselves as a nation.

Since its inception, the United States has struggled to reconcile its democratic commitments with undemocratic practices. The “city on the hill” has had to grapple with, even fight over, the disturbing presence of its slaves and their children. From early colonial petitions, emigration schemes, abolitionism, and the Civil War, and to the black freedom struggles of the mid-20th century, race matters have haunted our national promise — casting in grisly relief the unsightly side of American democracy. At the heart of our national malaise, at its very core, has been an adamant refusal to accept black folk as truly American — a refusal to accord them dignity and respect and to recognize their central place in the making of this nation.

Obama’s presidency represents, for some at least, a final ritual of expiation — a purging of the wages of our national sins. We finally can call this place home. But this view — and I believe it is true, to a point — when combined with Obama’s incorporation into the traditional narratives of American exceptionalism, only deepens our national racial malaise. It seems that Obama’s election was the result of a Faustian bargain: that race can no longer be so easily, as if it ever was, invoked in public conversation about national policy. It seems that our first African-American president and the efforts to account for his presence occasion the most recent iteration of what Ralph Ellison brilliantly described as the “fantasy of an America free of blacks.” Ellison published in 1970 an insightful essay titled, “What America Would Be Like Without Blacks.” There, he rightly rejected any attempt to deny the centrality of African-Americans to this fragile experiment in democracy: Our style, our language — indeed, our very presence — are essential to the distinctiveness of American life. That presence also calls attention to the contradictions that have shadowed our country since its inception, and it is here that the American fantasy takes root. Our national effort to rid ourselves of the great scandal of the United States — that “recurring fantasy of solving one basic problem of American democracy by getting ‘shut’ of the blacks through various wishful schemes that would banish them from the nation’s bloodstream.”

Barack Obama’s presidency ironically gives new life to this fantasy (and we are weaving a past to account for it). For some, he can’t talk explicitly about racial inequality without being accused of engaging in bad identity politics; if he chooses to do so, he must delicately balance his formulations with talk of self-help and personal responsibility. African-Americans are not completely banished; our presence, however, no longer disturbs and disrupts America’s hubris. We are now its face. To be sure, President Obama is not the beginning of some postracial era. What we are witnessing is a deepening of our national pathology — a scandalous silence about the various ways racism continues to impact the life chances of so many of our fellow citizens — as some seek finally to “get shut” of blackness. What is happening, right before our very eyes, is an attempt to account for the novel — Obama — by appealing to a past that confirms our inherent goodness. That appeal secures our national conscience in the illusion of innocence, an innocence that finally can be protected from the wounds of “our Negroes,” because, for some, they have now been rendered truly and ironically invisible.

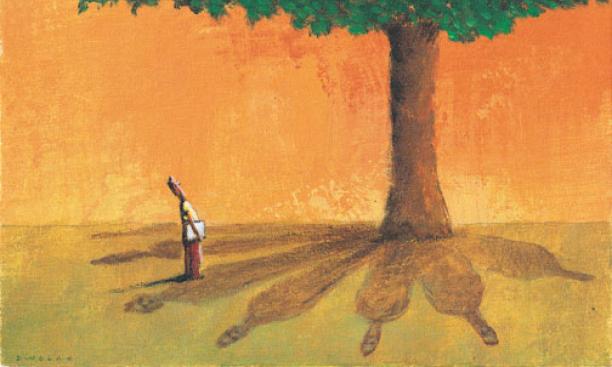

In 1951, in an essay titled “Many Thousands Gone,” with a white narrating voice, James Baldwin wrote: “Time has made some changes in the Negro face. Nothing has succeeded in making it exactly like our own, though the general desire seems to be to make it blank if one cannot make it white. When it has become blank, the past as thoroughly washed from the black face as it has been from ours, our guilt will be finished.” Obama, blank — a purging ritual. Baldwin went on to write in that same essay: “In our image of the Negro breathes the past we deny, not dead but living yet and powerful, the beast in our jungle of statistics. It is this which defeats us, which continues to defeat us, which lends to interracial cocktail parties their rattling, genteel, nervously smiling air: In any drawing room at such a gathering the beast may spring, filling the air with flying things and an unenlightened wailing. Wherever the problem touches there is confusion, there is danger. Wherever the Negro face appears a tension is created, the tension of a silence filled with things unutterable. It is a sentimental error, therefore, to believe the past is dead; it means nothing to say that it is all forgotten, that the Negro himself has forgotten it. It is not a question of memory. Oedipus did not remember the thongs that bound his feet; nevertheless the marks they left testified to that doom toward which his feet were leading him.”

The novel — the emergent, as Mead described it — calls for a past that accounts for it. Simply fitting Obama into an American narrative of exceptionalism fails in this regard. It is not enough to say, “Come, you are now a part of America, a part of Princeton”; it requires a fundamental re-examination of what we mean by Princeton — what we mean by America.

To begin to account for this moment requires of us, in part, an existential encounter with the fullness of our history and the historical wounds (that volatile mixture of history and memory) that reside therein. You can’t rush past that to some utopia. Those strange fruits dangling from poplar trees — you can’t rush past that. Those worn souls who struggled for basic civil rights in the South (many of whom suffer from something akin to post-traumatic syndrome) — you can’t rush past that. Those who languish in ghettos with no possibility for a decent wage, an adequate education, any possibility beyond the misery of their circumstance — you can’t rush past that. The tales of our dead — we can’t rush past them.

Still, we can’t linger for too long, or rot there. One must strike a delicate balance between piety and self-reliance. Ralph Waldo Emerson urged us to read history in order to discover how it might serve us in this insistent present. Emerson’s words still ring true: “The dead sleep in the moonless night; my business is with the living.” But for those whose skin bears the markings of a different journey, the business of living requires coming to terms with the dead — precisely because their ghosts continually haunt.

The great force of history comes from the fact that we carry it within us, unconsciously are controlled by it in many ways. History is present in all that we do. It scarcely could be otherwise, since it is to history that we owe our frames of reference, our identities, and our aspirations. To recognize history’s presence in us is to understand the absolute necessity of fingering its jagged edges in order, if just for a moment, to prick our frames of reference and to unsettle our established identities. For Baldwin, and I agree, the past orients us appropriately to the tasks of self-creation and of reconstructing American society.

In great pain and terror, one begins to assess the history that has formed one’s point of view. Each enters into battle with that historical creation — oneself — and attempts to re-create oneself according to a principle more humane and more liberating; one begins the attempt to achieve a level of personal maturity and freedom that robs history of its tyrannical power, and also changes history.

We, America or Princeton, cannot discard the past. It is what it is. If we are to move forward, we must confront honestly this nation and this institution’s history in all of its complexity and see how the imprint informs and shapes our choices. Confronting them allows us to break loose from “their tyrannical power,” as Baldwin said, so that we may imagine ourselves, the nation, and the University anew.

History’s ghosts occasion an opportunity, burdensome though it may be, to reflect on the difficulty of belonging. Baldwin placed much faith in shifting the object of our concern: We turn to the past to account for the urgency of now and to better equip ourselves to invade the future intelligently and with love. In the end, I accept Princeton’s past as I do America’s — not out of reverence, but because of an unyielding faith in future possibilities made possible by our presence here today. It is a wager: that memory can work on history to open up space for those of us who struggle to forge a distinctive life in light of the wounded lives already lived.

By Russell Nieli *79

Russell Nieli *79 works for the Executive Precept Program sponsored by Princeton’s James Madison Program and is a lecturer in the politics department. He recently completed a collection of essays dealing with affirmative-action policy and the origins of an urban black underclass.

I often have asked students in my politics precept classes to perform the following thought experiment. “You’re going to die tomorrow and will be reincarnated the next day. God offers you two choices. Either you will be reborn into a white working-class family in a lower-middle-income, white-ethnic community in Brooklyn, or you will be reborn into an upper-middle-class, black professional family, living in an upper-middle-class neighborhood in Forest Hills, Queens. You will not remember your present incarnation and have no reason to maintain any continuity with it. Which rebirth do you choose?”

Some readers may be surprised to learn that 90 to 100 percent of students of all races to whom I have posed this question say they would rather be reborn into the upper-middle-class black professional family living in an affluent neighborhood than into the white working-class family living in more modest circumstances. White skin color may still have its privileges in America, but they seem to these post-civil-rights-era students much less important than class advantages.

The most nuanced and perceptive answer I ever got to the question came from a black female student: “If I knew that I would have the same academic talent that I have now,” the student explained, “I would choose the poor white family. Having white skin still has many advantages, and it is easy to get a high-paying job in this country if you are smart in school.” But, she continued, if she were an average or below-average student, she’d prefer to be born into the rich black family — because affluence brings many advantages, and it’s difficult for mediocre students to find lucrative jobs regardless of their race.

This student didn’t know it, but she was reflecting what labor economists and other social scientists have been saying for many years: Since the middle of the last century, America has been experiencing a “declining significance of race” — the title of a book by Harvard sociologist William Julius Wilson — and a corresponding rise in the significance to social and economic advancement of formal education and developed cognitive skills. While these latter factors are related in important ways to family and neighborhood background, they also are tied intimately to individual talent and temperament. America has become a very kind place to the academically talented, hardworking, and ambitious students of all races and ethnicities — that is, the sorts of people who wind up at places like Princeton.

Which brings up the case of Barack Obama. What better example is there of how far talent, ambition, hard work, and a focus on what one wants to achieve in life can take you today in America than Barack Obama’s meteoric career as Ivy League student, Harvard Law Review editor, community organizer, law school professor, local politician, U.S. senator, best-selling author, and ultimately president of the United States? I have serious problems with many of Obama’s stated views. But it is clear that Obama is a man of great talent, oratorical and otherwise, and that his success in so many fields of endeavor and his ability to do so well among white voters in the 2008 election are the culmination of a long-term trend in America toward greater appreciation of merit, regardless of one’s ethnicity, gender, or race.

When one considers that 63 percent of respondents in a 1958 Gallup poll said that if their political party “nominated a generally well-qualified man for president and he happened to be a Negro” they would not vote for him, one gets a sense of how far America has advanced along the meritocratic path. While many black voters — and some guilt-ridden whites — no doubt voted for Obama because of his race, his impressive showing among white independents and young people clearly was based on the perception that he was a fresh voice and a gifted speaker with many talents of intellect and temperament that would make for an effective national leader.

The Obama success has provoked the claim that we have entered an era of a “postracial America.” At first blush the phrase strikes me as utopian silliness, since it ignores the inevitable intergroup tensions and hostilities that are inextricably a part of any multiracial, multiethnic, multireligious society. Nevertheless, insofar as “postracial” conveys the idea not of utopian transformation but of the more modest claim that the many racial, ethnic, and religious identity groups to which Americans belong are considerably less important than they once were in determining success in America, the phrase conveys an important truth.

Race, ethnicity, and religious identity clearly are less important determinants of who gets ahead in the United States today than was the case in the long period of WASP ascendancy — hence my students’ preference for being born into a well-to-do black family over a poor white one. Barack Obama’s election is only the latest development in a long evolutionary process that accelerated after the Second World War, by which members of various minority groups have ascended to positions of power and influence. It is an important milestone — like the election of John Kennedy as the first Catholic president — though it is not the Holy Grail.

To use an older phrase of classical liberalism, it is part of an important and much-welcomed trend in which careers are increasingly “open to the talents.” The widespread belief in this principle is one reason so many Americans continue to oppose race- and ethnicity-based preferences in employment and other areas of American life, and why a majority of the members of the U.S. Supreme Court have been eager to invalidate most such policies through the vehicle of the 14th Amendment’s equal-protection clause.

But for many there is a sinister undertone to the phrase “postracial.” Michael Eric Dyson *93, for instance, has said that while it surely is good that America should seek to become “postracist,” it is not good to strive to become “post-racial” — at least if that means people must abandon their cherished racial and ethnic identities to become full Americans. Here I find myself in agreement with my fellow Princetonian (though I have disagreed sharply with Dyson on many other issues concerning race). E pluribus unum (“out of many, one”) is one of America’s foundational ideals, affirming two equally important principles: We must show respect for particularized diversities (the pluribus), while at the same time affirming the importance of participation in a more encompassing civic and political realm (the unum) in which those diversities are transcended, without being destroyed.

This means that it is OK to have what older theorists of assimilation called “layered identities,” so that Irish-Americans, Italian-Americans, Chinese-Americans, African-Americans, Mormon Americans, Jewish Americans, and all those who cherish their “hyphenated and hybrid attachments” can be no less Americans than WASP Americans or those who have no group identity other than their American nationality. While all individuals and groups in the United States are called upon to affirm certain basic tasks and ideals — like respecting democracy and the rule of law, seeing to it that their children become educated and learn English, respecting the Constitution — the idea of liberty in America generally has encompassed the notion that outside the limited civic and political realm where we share a national identity, people are free to seek happiness and fulfillment in their particularized communities. A “postracial America” for many would mean the destruction of these communal attachments and hybrid identities, the toleration of which, I believe, has contributed to America’s relative success in assimilating the diverse peoples of the globe.

The Harvard philosopher Horace Kallen, who wrote in the period between the two world wars, had many wise things to say on these matters. Resisting the extreme Anglo-Saxon assimilationists of his day who enjoined against “hyphenated Americanism” and who reached menacing proportions in the 3-million-strong Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s, Kallen, a Jew, spoke of America as a “multiplicity within unity” of peoples from many diverse ethnic and religious communities. It was within these “organic” communities, Kallen wrote, that we nurture our “preferences of the herd type in which the individual feels freest and most at ease,” and it was important for the well-being of everyone, he believed, that citizens not be required to abandon these communal attachments to become fully American.

Around the same time Kallen was defending hyphenated Americanism, the historian Marcus Hansen was fleshing out his law of immigrant succession: What the second generation often tries to forget about its ancestral roots, subsequent generations desperately try to recover and preserve. Hansen and Kallen understood that we all crave a sense of belonging and place, and that America offers the cherished freedom for people to mold and select their own place-defining narratives.